On the night of Friday, October 27th, 2023, I sat in bewilderment in front of the Al Jazeera livestream as Israel indiscriminately bombed the Gaza Strip. The bombs fell under cover of total darkness, produced by an Israeli-enforced power and telecommunications blackout. A schizoid world picture shone: one half of the split screen blasted live images of the Gazan cityscape, spasmodically illuminated by the bombardment, as the other half aired the methodical proceedings of the United Nations General Assembly.

The UN delegates in New York voted with more than a two-thirds majority in favor of a resolution demanding an “immediate” and “durable” truce. The objectors were effectively limited to Israel itself the United States, save a scattered others, like the handful of island states that are U.S. clients. But if there’s one fact that I still remember from my time as a participant in the Model United Nations program—where high schoolers cosplay international diplomacy in formal business attire—it is that U.N. General Assembly resolutions are non-binding.

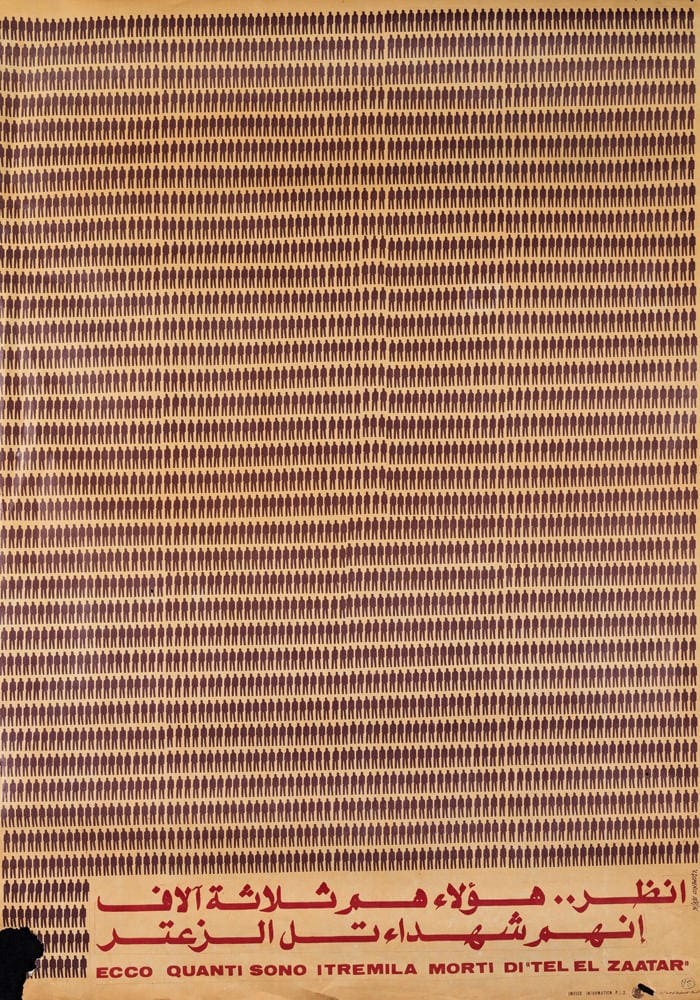

At the time of writing, another General Assembly vote has taken place, with a majority again calling for a ceasefire. And yet a lasting ceasefire has not yet been secured. Population transfers are proposed on a daily basis by the Israeli establishment. Some sources estimate the number of Palestinian dead, (with some projections preemptively including the thousands missing), to be near 32,000. But already, on that night of the first blackout, the delegates to the UN appeared as impotent in the face of the war as I felt passively watching the Qatari state-owned channel.

Three months later came South Africa’s landmark case accusing Israel of genocide at the International Court of Justice. The case notably situates the current onslaught within the long history of displacement and extermination of the Palestinian people since 1948, when 750,000 Palestinians were expelled from over 400 villages, an event aptly known as the Nakba. It has also been commended for its bypassing of cynically truncated frameworks that trace the current situation only as far back as the 1967 occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

The South African delegation mounted a meticulously documented and argued case, adhering to the U.N. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Israel responded by disputing the basis of South Africa’s motion on mere technicalities, admitting not a day of historicization before October 7th and summoning the same bedraggled tropes of military conduct: human shields on the side of Hamas, and humane airborne warning leaflets on the side of the IDF. To hear the Israeli delegation tell it again: if Hamas has used at least one residential building or hospital to fire rockets, then Israel is allowed to bomb, in self-defense, at least all of the residential buildings and hospitals of Gaza.

Israel’s counterargument against the accusation of genocide, citing the exigencies of military self-defense against terrorism, was to be expected. Genocide scholar Dirk Moses has pointed out the difficulty in matching the definition of the United Nations Convention on the Punishment and Prevention of Genocide (UNGC)—modeled as it is on the Holocaust—with the types of mass death inflicted even by the most deliberately exterminatory modern military offensives.

As a result, proving that a genocidal campaign may be waged through airstrikes on civilian targets remains difficult. It is these shortcomings which Israel attempted to exploit, wildly mounting death tolls notwithstanding. (As far as death tolls are concerned, Israel has broken the record for deadliest conflict in the 21st century, with an average of 250 Palestinians killed per day in Gaza since the start of the war.) Palestine is indeed frequently dubbed the “exception” to the humanitarian consensus, but perhaps it is more constructively thought of as a limit-case, laying bare the intrinsic shortcomings of the international human rights legal apparatus.

The Genocide Convention was established in 1948 by the victors of World War II as a core component of an international legal system that ultimately protected their right to declare war in pursuit of the maintenance of political and economic security and hegemony. This took place in the same year that the State of Israel was established, made possible by the original Nakba. It was also the year of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the 58 members of the United Nations General Assembly, as well as the introduction of Hannah Arendt’s concept of “the right to have rights,” which first appeared in English that year in an essay titled “The Rights of Man: What Are They?”

Examining the concept of human rights as it had crystallized alongside the Declaration after WWII, Arendt writes that 20th-century man was now liberated from “nature” as the bestower of rights after the French Revolution, just as the 18th-century (French)man was liberated from the contingency of “history” as the bestower of rights. Now, “humanity” was understood to be the universal originator. This pointed to the contradiction at the heart of the Declaration: installing such a broad notion as “humanity itself” as the guarantor of rights did nothing for the stateless peoples who were denied agency and participation in this “humanity” because they lacked a coherent and sovereign political community.

Before the Nazis could strip European Jews of their right to live, they had to strip them of legal status, sever their links to the rest of humanity by confining them to camps and ghettos, and ensure that they belonged nowhere else in the organized world. Their right to have rights—which is to say their right to belong to a political community that might begin to attempt to enforce their human rights—had to be nullified first. Arendt then points to the limit of the attempts of the “best-intentioned humanitarians” to institute new, universalizing human rights frameworks: she asserts that only after the restoration of the national legal rights of Jews in the State of Israel could their human rights also be restored.

In the intervening years of the 20th century, as the U.S. ascended to the status of global hegemon, there proved to be other instances in which international law became “non-justiciable”—cases that were not predicated on the statelessness of a subject population. The constitutive indeterminacy of international law, its quality of not being uniformly enforceable, is exemplified by the non-binding quality of U.N. General Assembly resolutions, as well as by the baldly imperial and hierarchical structure of the U.N. Security Council, the only U.N. body capable of issuing explicitly binding resolutions.

Perry Anderson, in a New Left Review essay titled “The Standard of Civilization,” provides a pithy historical example of this indeterminacy: the United States used NATO to launch a war against Yugoslavia in 1998-1999, instigating the conflict. The intervention went forth even after they failed to engineer a Security Council resolution that would authorize such a war, and in explicit violation of the U.N. charter, which forbids wars of aggression. U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Anan stated that although NATO’s actions might not be “legal,” they were “legitimate.”

Anderson goes on to explain that the use of human rights as a new “standard of civilization” is rhetorically consistent with international law’s geostrategic instrumentalization by the hegemonic world powers. A given country or political community’s presumed and/or putative respect for human rights—its level of “civilization”—becomes the standard for determining in turn whether the international community bears any responsibility to uphold the human rights of its people. If Gaza is deemed to be ruled by a terrorist Islamist organization, then its inhabitants will in practice have dropped out of the realm of universal rights.

This “global standard of civilization” manifests in its most bellicose registers in the wartime speeches of countless heads of state, who reiterate that the slaughtered Palestinians in Gaza voted for Hamas, or those who dismissed the numbers of the dead by citing their source as the “Hamas-run Ministry of Health.” The obverse is, of course, the talking point that “not all Palestinians are Hamas,” as though whether they are or are not Hamas supporters should have any bearing on whether they are to be imminently exterminated.

But outside of times of war, the “standard” is promulgated more calmly and systematically in countless international diplomacy and policy papers. The Marxist legal scholar Ntina Tzouvala has argued that the notion of “civilization” in international law is not a precise and definite concept, but rather a pattern of argumentation that sets up conditions for the inclusion of certain racialized political communities in the domain of international law. Most often, their status is dependent upon their embrace of capitalist development. Yet it is precisely this forced imposition of capitalist development on the peripheral world, always underpinned by neocolonial extraction and unequal exchange, that foments the proliferation of innumerable local tyrants, right-wing paramilitaries, clientelist and crony economies, and other such symptoms, which are considered disqualifying from the global standard of human civilization.

In addition to accounts describing the regime of human rights as a civilizational standard that operates across global spatial divides, there are others that question its mainstream use as a historicizing temporal marker, declaring a tidy conclusion to the era of militant political struggle. In After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights, Robert Meister theorized that just such a hegemonic Human Rights Discourse, congealing after the Cold War and the fall of South African apartheid, claims to supersede the “era of revolutions” in the Western world, beginning with the French Revolution and ending with the fall of Soviet Union.

The militants and radical intellectuals of that era of revolutions conceived of justice as a permanent struggle, or as an asymptotic limit that must be constantly approached. This militant conception of justice as struggle runs counter to another idea of justice, latent in Human Rights Discourse, that understands political questions to be mostly settled, and militant resistance and revolution to be categorically off the table.

Human Rights Discourse’s idea of justice as reconciliation proclaims that victims of past or continuing injustice must reconcile themselves to an order of reality in which the beneficiaries of past injustice are allowed to maintain their spoils. They must not seek to overturn that order by any means, no matter how non-violent, because those means are destined to initiate another cycle of human rights abuses. Justice as reconciliation would require Palestinians to both lay down their arms and relinquish any claims of harm, the redress of which might entail negotiating the right of return and redistribution of wealth, land, and commons in any future state formation.

The bankrupted Oslo process may be thought of as an example of failed justice-as-reconciliation, doomed from the outset by the egregious territorial concessions made to Israel, the pretense of two-statism without any true sovereignty for Palestinians, and the escalating domination of the Israeli establishment by far-right settler ideologues. In this light, it becomes clear that the mandate of human rights is wielded as a cudgel against any “unreconciled” victims, who are effectively dehumanized as fanatics and extremists. This is perfectly exemplified by the demonization of all Palestinian resistance, across a spectrum that runs from BDS to armed struggle.

As deployed by the United States in conjunction with the continuing War on Terror (invoked wherever Islamist forces might threaten American foreign interests), human rights even come to appear more akin to a religion than to uniformly enforceable law. Indeed, Meister argues that Human Rights Discourse bears the marks of a secularized Judeo-Christian world religion claiming to supersede on a global scale the evil, pagan, and cyclical past of revolution and counterrevolution. (In mainstream usage, “Judeo-Christian” is synonymous with “Western civilization.”) Provocatively, Meister suggests that the Judeo-Christian unconscious of Human Rights Discourse is manifest in its universalization of Jewish suffering in the Holocaust as the sacrificial usher of a new era, in a manner analogous to the early Christian Saint Paul’s description of Christianity’s birth through the universalization of the suffering of Christ, the Jewish Messiah. The most grotesque pitfall of Human Rights Discourse is that it accompanies a global order which allows Israel to be the most glaring Western exception to 21st century humanitarianism—giving fuel to old and new varieties of antisemitism, which take Jewish peoplehood to be exceptional or intrinsically malign.

In Meister’s description, the cardinal principles of Human Rights Discourse state that the victims of past atrocity are passive and innocent, the perpetrators are the handful of leaders who were tried at Nuremberg or The Hague, and most beneficiaries of injustice are allowed to keep their benefits if they acknowledge that the atrocity belongs to a time which must be placed in the past. Nowhere is this as clear as in present-day Germany.

There, post-reunification Holocaust remembrance culture (Erinnerungskultur) has papered over a denazification process that was grossly incomplete at best, and actively undermined at worst, especially in the former West. This instance of justice-as-reconciliation is now supplemented by the nebulous notion that Israel’s security is Germany’s “Staatsräson,” or reason of state, as articulated by Chancellor Angela Merkel and reiterated by Olaf Scholz. The Staatsräson has become a pillar of German national debate in the wake of October 7th.

While declaring steadfast support for Israel as it wages war on a besieged civilian population, liberal humanitarian Germans empathize and identify with the exterminated European Jews as abstracted and idealized innocent victims. Germany has been ostensibly relieved of its “Jewish question” so totally that German commentators will go so far as to proclaim that due to its unwavering support of Israel, Germany is now in itself a victim of antisemitism.

Israelis, however, are not afforded this kind of relief from Palestinians. The Nakba, which founded the State of Israel, was not sufficiently successful at solving the “Arab question,” and so Palestinians remain a scourge in the eyes of the ethnostate. Meister notes that the Israeli historian Benny Morris—whose work has extensively documented the ethnic cleansing of 700,000 Palestinians in the Nakba, though not without omissions and obfuscations—has admitted that it would have been preferable if Ben-Gurion had finished the job and fully disposed of all Palestinians, from the river to the sea. Following this logic, Morris implies that it would have been for the better if Israelis in the present could commemorate a more total Nakba, considering it a necessary sacrifice for an Israel without an “Arab question,” finally placing the Nakba firmly in the past.

As for the Palestinians who were indeed eradicated by the Nakba and its ongoing permutations, including the current assault on Gaza: they are identified as martyrs by the Palestinians who outlive them, foreclosing their status as passive victims of past atrocity. Instead of sacrificial offering for an Israeli national pact, they are claimed as martyrs for Palestinian resistance towards national liberation. Martyrdom refuses to make passivity and innocence prerequisite criteria for recognizing victimhood. It insists that a death took place in struggle.

Cue the political and epistemic unease, from left-wing squeamishness to outright racist revulsion, that accompanies the discourse of Palestinian resistance—with its emphasis on martyrdom and the prominence of Islamism in its ranks—in most Western public spheres. There is little need or room here to bother with right-wing responses to rhetorics of Palestinian resistance, but multiple left-wing currents have consistently rejected the terms of struggle set by Palestinians themselves, not least in the wake of October 7th. Some leftists have expressed that they are uncomfortable with martyrdom discourse, due to its overemphasis on finding meaning in death, even when they believe in the veracity of the Palestinian struggle. Others admitted that it would be far easier to voice solidarity with Palestinian armed struggle had it not come to be dominated by Islamists after the waning of the secular leftist factions.

Still others facilely prescribed that Palestinians partake in “organized democratic mass politics” in place of armed mobilization, sidestepping the absence of a contiguous body politic that is not shattered by colonial apartheid, even in the most peaceful of times. And a recent “Leftist Renewal” open letter lambastes any “accommodation with Islamism” among the left as reactionary, completely ignoring the annals of Arab leftist ethics of dealing with Islamism and discounting the fact that a majority of those in Gaza who choose to resist through armed means do so under an Islamist banner.

More to the point was Joshua Leifer’s call for a “humane” left, made in the cast of Michael Walzer’s 2002 essay Can There Be a Decent Left?, which claims to insist on “the possibility, on the moral imperative, of bending what others take to be history’s iron tracks,” against the supposed primordial bloodthirst of certain segments of the left who did not immediately repudiate Palestinian armed resistance after October 7th. What Leifer does not admit is that “history’s iron tracks” were not exactly running according to either Hamas’ or the left’s master plan when October 7th happened.

It seems that Leifer would have leftists everywhere, especially those in the imperial core, proclaim their own humanity and moral untaintedness as a precondition for entering into discourse, foreclosing any historicization of why it is that the colonized and besieged have resorted to violence. (Another fact that Leifer does not address is that Walzer’s appeal for “decency” was made against leftists who opposed the war on Afghanistan: “decency,” like “humaneness,” only ever applies to those already within the remit of the global standard of civilization.)

These responses vary and should not be conflated. But they all attempt to pass off an a priori humanitarian idealism, one that does not admit the concrete realities of its own inapplicability to and instrumentalization by empire, as an abiding commitment to a moral and secular humanism. My contention is that these proposals are obfuscatory in the struggle for a free Palestine—just as confusing as a reckoning with a Palestinian discourse of martyrdom, accompanying both armed and non-violent struggle, secular and Islamist, can be enlightening.

In civilized company, there is always a too-muchness to the discourse of martyrdom: it is too anachronistic, too theological, too culturally specific, too transparent about its death drive, too realistic about the power valences of battle, too dismissive of the victimized’s innocence and the humane sympathy that innocence might engender. It is this apparent excess of martyrdom discourse which must be accounted for against the present-day shortcomings of humanitarianism in Gaza.

In 1972, it was not too much for Ghassan Kanafani, a leading member of the secular Marxist and revolutionary socialist PFLP, to credit Sheikh Izz al-Din al-Qassam with what he called the revolutionary “Guevarist” sense of martyrdom in the Palestinian struggle. In his 1972 pamphlet The 1936–39 Revolt in Palestine, Kanafani ascribes to al-Qassam, and to the Qassamist movement of November 12th to 19th, 1935, a pivotal role in the course of the revolt of the late 1930s, as well in the national liberation struggle at large.

To his followers—in large part landless ex-farmers dispossessed by the Zionist acquisition of land and its imposition of exclusive Jewish labor policies—the Syrian cleric, educated at Al-Azhar in Egypt, embodied the then-novel project of combined national and religious liberation. As opposed to the majority of Palestinian nationalist leadership who avoided confrontation with British mandatory authority at the time, al-Qassam advocated opposing both British forces and Zionist expansion.

Kanafani wrote that according to many accounts, al-Qassam was still in the early phases of spreading the call of armed revolt when he was discovered with his men in the Ya’bad Hills west of Jenin on November 12th. Facing likely defeat, he beseeched his men to “die as martyrs.” Al-Qassam’s funeral was primarily attended by his impoverished followers. But in the following weeks, the traditional leadership of the national movement could no longer maintain its indifference to the popular mobilization that killing al-Qassam had triggered, choosing to participate in the mass rallies and speeches that took place forty days after his death. The subsequent events would come to be known as the Great Palestinian Revolt.

One purpose of recounting the brief historical episode of the 1930s Qassamist movement is to underline that organized Islamist factions have been an inextricable part of the Palestinian struggle since well before the Nakba. It is also to emphasize that Kanafani’s appraisal of al-Qassam is an example of the varying and complex ways of dealing with fellow Islamist movements which Arab leftist movements have developed over the years. At their best, these approaches are both critical and pragmatic, rarely devolving into blanket moral condemnation or idealist rejection.

Another purpose is to point to a long-standing genealogy of Palestinian martyrdom, one that is based in concrete confrontation with a far more powerful and imperious oppressor. Palestinian martyrdom crosses the boundary between secular and theological, suffusing the gap left by the absence of the right to have rights. It acknowledges that Palestinian life and death are not ruled by a regime and political community of their own making, in which their rights may be codified and exercised. It is both a mode of pragmatic action and a method of eulogization: martyrdom exists before and after every unjust death which occurs before the colonizer ceases to rule over the political community.

Both the Arabic and Greek etymologies of the term, shahada and martur, entail an act of witnessing. Open to interpretation is whether the deceased is a witness to earthly injustice alone or whether they are also witnessed by God in their passing. But the martyr is surely to be witnessed by those belonging to the political community that they leave behind. As a method of eulogization, martyrdom forges a continuity between those who die in battle and those who die going about a common life, refusing to leave the land if they even have the choice to do so.

It is for these reasons that the claim to martyrdom is not fully congruent with mourning as a humanitarian and ethical duty. Palestinian writer Abdaljawad Omar, writing in response to Judith Butler’s proposal to widen the “compass of mourning” such that it also incorporates Palestinian life, finds shortcomings in their attempt at ethical inclusivity. Butler’s gesture of ethical mourning requires a flattening of power differentials, its act of inclusion moving centrifugally from the metropole, in which the academic sits towards the periphery of where the liberation struggle is waged.

To acknowledge and echo the methods of eulogization which Palestinian themselves have devised for their dead is to recognize that ordinary mourning is often made impossible by the colonizer. It may also be purposefully delayed or confined behind closed doors. We are reminded of the long tradition of Palestinian mothers rejoicing and ululating at the funerals of their martyred progeny, refusing to show sadness in public under the colonizer’s watch. A claim to martyrdom rejects the meaninglessness of death, insisting that an individual death is part of a collective movement towards liberation. Mourning can only take place after liberation: only then can there be public grief where before there were only the ululations of the bereaved.

The right to mourn is only one among all the other rights that are deferred in the absence of the right to have rights. In the meantime, martyrdom sutures the political community ruptured by the colonizer’s state solutions. Regardless of whether the International Court of Justice recognizes the assault on Gaza to be a genocide, there is one lineage in Palestine that cannot be broken by Israel: Al-Qassam is a martyr, Ghassan Kanafani is a martyr, Shireen Abu Aqleh is a martyr, Hiba Abu Nada is a martyr, Refaat Alareer is a martyr, and every girl or boy killed in their home will have been martyred.

Palestinian resistance and martyrdom upend the world of human law—even when, and precisely because, they are the viscera of being human. May they inaugurate a new human law.♦