In Richard Hell’s novel Godlike, protagonist Paul Vaughn, middle-aged and unwell, looks back on his relationship with an extraordinary teenager named R.T. Wode, or “T.” It was New York City in the 1970s and they were both poets—Paul in his 20s, somewhat established but bored, whereas T. has recently arrived in the city and appears possessed by something brilliant and infernal. They shared drugs, had sex with each other, and generally raised hell wherever they went. T., the enfant terrible, activated an electric current in Paul that would inevitably find the ground, and in dramatic fashion.

Students of literary history may note the resemblance here to accounts of the actual relationship between Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) and Paul Verlaine (1844-1896) in the early 1870s in Paris. That context is not particularly relevant to Godlike: plot is of little import to the novel’s force, which lies in its language and its sensual, sordid imagination. But the resemblance is not exactly coincidence; it’s also a tacit conceit. Hell’s own association with Rimbaud is a long one, and he will admit that lazy journalists are only partially responsible for it. It’s neither their fault nor his, for example, that his friend and partner in poetry and music for much of the ’70s was Tom Verlaine (1949-2023).

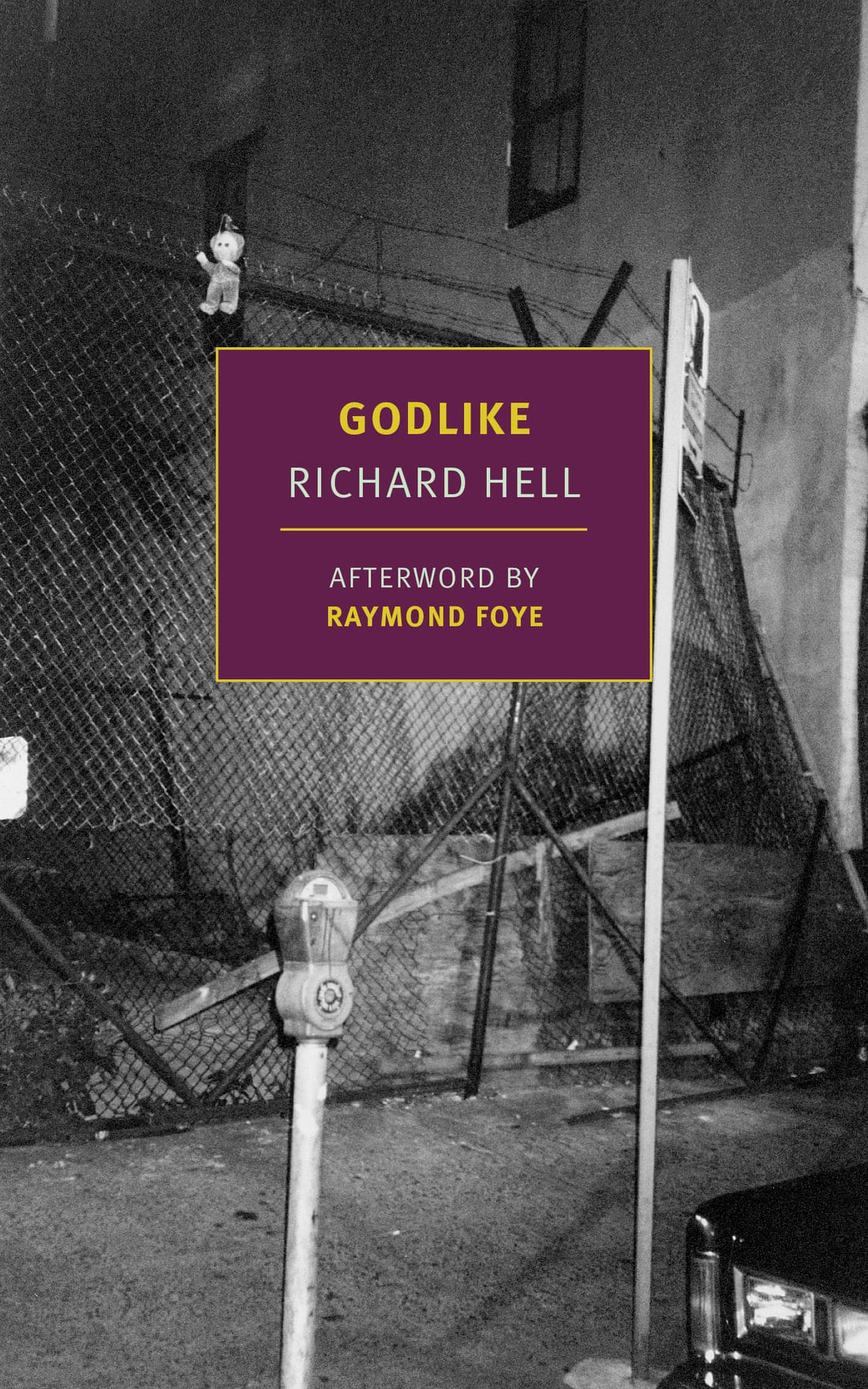

Originally published in 2005 by Akashic, Godlike appears in a new edition this week from New York Review Books Classics, with an afterword by the writer and curator Raymond Foye. Hell has written many books of poetry and prose since the early 1970s, including the novel Go Now (1996); a compendium, Hot and Cold (2001); Massive Pissed Love: Nonfiction, 2001-2014 (2015), a collection of the essays and criticism he’s written regularly for little magazines and glossy publications alike; a well-received autobiography, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp (2013); and, most recently, a book of poems called

Hell—as you may be aware—was a musician too, between about 1974 and 1984. There is little to note about this part of his C.V. that hasn’t been documented already and at considerable length; it suffices to say that from his form, many others were cast. In a jotting published in What Just Happened, he describes his frustration with studies of art and artists that exaggerate the historical importance of their subjects, himself included. “We’re all what we have to be,” he writes.

I spoke to Hell in the East Village, where he’s lived in the same apartment since 1975. It has been written that he looks younger than his years and I can report that this is true: he is 76 but his aspect and movements might easily be those of a man in his 50s. My sense is that it’s a certain relationship to art that has kept Richard Hell youthful. His most recent published works—essays in Poetry, the British zine Scary Boots, and the online publication Zona Motel—suggest a writer who is still “fully sensitive to reality,” as he puts it in one of those essays, on the way that art allows one to live. At age 16 he quit school to become a New York poet and a New York poet he remains, at ease on the street and still electrified by books.

Richard Hell’s Godlike is now available from New York Review Books.

♦♦♦

Andrew Holter: The first time I read Godlike, maybe fifteen years ago, I knew nothing about Rimbaud and Verlaine or that this novel had anything to do with them.

Richard Hell: For the original edition of the book I persuaded the publisher not to reveal that I used Rimbaud-Verlaine as a pattern for the plot, because I didn’t want people to know—not because I was hiding it, out of thinking it would somehow reduce their opinion of the book, just because I didn’t want that to be the point of the book. I wanted people to read the book on its own merits. He agreed. So the first reviews, those people didn’t know, and they didn’t refer to Rimbaud-Verlaine. It dawned on me, though, that once anybody notices, the cat’s out of the bag and there’s no point in continuing to publish it without reference to that.

It’s cool to hear that when you originally read it, you didn’t pick up on that. Was it different to read it again with that knowledge?

AH: Absolutely—but what you just said makes me wonder if my first reading was purer, in a sense, and if my instinct this time around to read the details of your autobiography into the novel was a mistake.

RH: As a writer I can have my ideal mental position for the reader. I can think of how, ideally, I would like a reader to come to it. But I’m the same way as you’re saying when I read: I immediately want to know the relationship of the author’s life to the book.

AH: But you didn’t want to determine how people would read the novel.

RH: If I could keep people from reading it as being a version of Rimbaud-Verlaine, yeah, because that’s not what it is. I wasn’t trying to capture Rimbaud and Verlaine. I was using that story as a convenience for myself because I wanted to write about street poets, and I’m really bad at plots and I didn’t have any story.

I’m not really interested in plots. Even the writers who really depend on plots are often not interested in plots. Raymond Chandler, for instance. There’s that famous story about when William Faulkner and Howard Hawks were making The Big Sleep. It’s a detective story, the definition of a book that’s about plot, and they couldn’t figure out what was going on. They contacted Chandler and he didn’t know either.

You love Chandler because of the prose style and the attitude and the setting; it’s not really about the story at all. I don’t think there are very many great books that have much to do with story, except to the extent that these stories serve as a pretext for the writer to show his stuff.

I thought it would be a disservice to both me and the reader to approach the book as, I’m giving you Rimbaud and Verlaine. On top of how that would be a distortion of what the book’s trying to do—if you’re at all knowledgeable about the history of Rimbaud and Verlaine and modern poetry, you’d come to it offended that somebody was deludedly arrogant enough to try and give you Rimbaud and Verlaine.

AH: Because only the poetry can do that?

RH: I don’t think you can tell what people are like from their poetry. Quite the contrary. People do not behave like their writing—that’s been my experience. I’ve often formed strong impressions of writers based on having read their books, poets specifically, and then been kind of shocked when I actually meet them and find out how different they are from what I would think they’d be like from their writing.

Consider somebody like James Schuyler, who was one of my personal references for the book. I just read his new biography. Anybody who’s interested in him is aware that in real life, he was damaged. Do you know much about him? He was a great poet of the original four—some people include Barbara Guest and make it five—of the New York School: Ashbery, O’Hara, Koch, and Schuyler. Three of them were at Harvard together. Schuyler dropped out of college, it was a no-name college anyway. I can’t remember what diagnosis he got, but he was frequently hospitalized for mental problems. His poetry is so serene, but all his life long he was losing it and chasing people with knives and rolling naked in his thorny rose garden, having to be institutionalized.

So, yeah, people aren’t like their writing.

And it’s not only that their poetry doesn’t necessarily say a lot about their personalities and behavior, but that announcing on the book that the story’s drawn from the relationship of Verlaine and Rimbaud creates a needless distraction. The book’s not about Rimbaud and Verlaine, it’s about sophisticated but anti-academic street poets imagined by me as living in New York City around the decade of the 1970s.

AH: Was Schuyler’s example on your mind for this novel?

RH: For the Vaughn character, sure, as were a few other people, like John Wieners. You probably don’t know any of these names. Wieners was one of the most hallucinatorily perceptive, moving poets of that era, and he was also at the mercy of his incoherent mental processes. Or Rene Ricard, who could inspire the roles of either Paul or Wode. He was a notoriously cutting, obnoxious provocateur of a guy living outside conventional society who was a real wit, too, and also often lovelorn and influenced by “recreational” drugs, like crack. Rene was such a provocateur and always wanted to embarrass people for thinking anything they said was interesting [laughs], though he was largely a pussycat with me. I published a pamphlet of his. That normally would be a dangerous undertaking, but he was encouraging.

Another person who helped me realize the T. character was Johnny Rotten. You could substitute his name for T.’s in that opening page to the novel, as a guy who just lives to offend.

The first time I met John Lydon was when he was Johnny Rotten in 1977, when me and my band had just headlined at a club in London. This was at the tail end of a tour we did opening up for The Clash. We had our own headlining gig in London, and all the honchos in the scene in London were at that gig. All the Clash. Lydon. Nancy Spungen was there. Siouxsie and the Banshees opened for us. It was all the inner crowd.

Lydon did something really uncharacteristic of him and jumped on stage after we got off and started this cheerleading, “Bring them back!”—like he riled up the audience to get us to do an encore, which was cool. I’d never met him. Then backstage, when the punk people were all milling around in our dressing room, there’s Johnny, and the first thing he says, specifically addressed to me, is, “God, you’ve got a big nose.”

He was like that: unpredictable. Just wanted to fuck with you.

AH: So you wanted to write about street poets, but the Rimbaud-Verlaine story—it’s not a coincidence that you reached for it. It interested you.

RH: I did a hell of a lot of research. I can show you, I have a whole shelf of Rimbaud and Verlaine, and I loved how I got the chance to riff on their own actual writings in places in the book. It just enlarged the area for fun.

AH: It’s a crazy story that no one has treated very well. There was that movie in the ’90s with Leonardo DiCaprio [Ed. note: Total Eclipse (1994)]—

RH: —It’s really impossible. Unless you’re Godard or somebody who can be a poet as a filmmaker. When has there ever been a good movie about artists? That question always comes up and I can’t remember any good answer. Can you think of one? Because if the artist is interesting enough to sustain a movie, you’re going to have to be more or less on the same level to do a movie that’s worthy of the artist.

AH: On that subject, I was sorry to hear about Amos Poe.

RH: People are dying, man.

AH: Why did Godlike present itself to you as a novel rather than poems?

RH: The way I move from project to project is pretty whimsical. I like moving between mediums, and it doesn’t have to do with some overriding aim. Because I work in so many different mediums—I was brought up to say “media,” but now you say “mediums”—I’m working on this poem, and then I’m writing something in my notebook, and I’m getting an idea for a piece of fiction, then I collaborate with an artist friend. I just kind of follow my nose. There’s not a pattern, you know?

But also a factor is that I have to make a living, and it’s easier to make a living from fiction than from poetry. Probably I’ve done more journalism than either. I would never be a teacher or anything. My whole life I’ve just supported myself from art. There’s been one period since I took up rock and roll in the ’70s when I had to get a day job again, trying to figure out how to make a living. I just don’t relate to the academic environment. I wasn’t going to write an epic poem. No, I knew I wanted to write another novel.

My fiction is usually about whatever is preoccupying me at the time. My first novel [Go Now], I wanted to try to capture the psychology of addiction. All that has gotten so ransacked in the past 30 years. Every other book is an addiction chronicle of some kind or another. In the ‘90s it was just starting. What I knew of addiction chronicles was Burroughs and a couple of jazz musicians that had done good books or books that were effective, evoking what it’s like to be a drug addict. I’d spent ten years addicted to heroin and it was kind of fascinating to me—the whole narrative of that, the places it took me, and I wanted to capture that in a novel.

I quit music in 1984 and quit drugs, overcame my addiction. I knew that I couldn’t go back to music for a few reasons. Probably the main one was that it didn’t suit me. I didn’t like being on tour. I didn’t like being some kind of spokesman. So I had to figure out what to do with myself. I had to make a living. That’s when I got the job to be a proofreader for a couple of years to make ends meet. Possibly I could act, I thought, because people had asked me to be in movies, even though I was not that comfortable doing it, but I had to make a living. I got an agent and went to a couple of auditions and I hated that. I couldn’t stand that whole process. I’m not good with rejection. I originally wanted to be a writer, but you don’t make a living writing poetry.

Always, my whole life, I’ve written poetry, some periods more than others. Sometimes, you know, only ten poems a year, but I’d always had that. It’s not a livelihood. So I thought of journalism, and that’s what I did. I was able to get a leg up, and people wanted more, but I knew that that wasn’t enough, that I was going to have to try to make real art in writing, and that meant a novel.

I’ve always dug novels. I don’t think of them as a step down from poetry. In fact, the thing I love about novels is how unbelievably flexible they are, how all the different forms of writing conceivable can be folded into a novel.

AH: There’s a lot of poetry in Godlike.

RH: There’s poetry that’s composed by characters in the novel and there’s poetry that’s translations of existing poems. And there are poems that are translations from English to English.

AH: What do you mean?

RH: Well for instance the character Ted, which was me imagining Ted Berrigan. Berrigan was hugely influenced by Frank O’Hara, as all those New York School poets really idolized Frank O’Hara, as Jim Carroll did, as James Schuyler did, as numbers of young poets have. Berrigan was smitten, so I thought it would be fun to have the couple of poems that I attributed to Ted in the book be me taking an existing Frank O’Hara poem and somehow trying to do an equivalent of it, with nothing superficially in common, nothing specific to the wording in common, but only underneath the surface. The tone, the activity… translating from English to English.

AH: Godlike is framed as a book written by Paul Vaughn in 2004 based on notebooks he kept while hospitalized in the ‘90s, which are themselves reminiscences of events in the ’70s. Did something particular inspire that choice?

RH: I had been thinking a lot, around the year 2000, about outliving my youth. It’s funny, going through time. When you’re a kid and in your first rush of being yourself, when you’re a teenager up through your 20s, it just feels like this is the way life is and you operate on that assumption. Then you live long enough and you find that as you age, things start to look different, so you’re constantly having to reorient yourself, if you’re self-conscious like I am.

It was a preoccupation: what does it mean that all these things that had driven you in your youth, you had a different reading of now, and you had to take that into account as you mapped out your plans and assessed your own behavior and prospects. So that was another thing I wanted to think about in the book: what does it mean to outlive your youth?

The abstract idea of wanting to talk about what it’s like to be a non-academic street poet had to have come before I hit on Rimbaud-Verlaine. That would give me the chance to talk about New York in the ’70s too, because I definitely wasn’t doing a historical novel, except to the extent it is a historical novel about the ’70s, a history that I knew firsthand. Coming up with the pretext, the setup for a novel has to do with finding one that will give play to things I have on my mind at that time.

AH: Godlike is not really autobiographical, but you lived in the world of the book. Did writing it warm you up for thinking about your autobiography? Do you think of the two books as connected?

RH: I’ve always felt like the only material we have is ourselves, and that’s only increased as I’ve aged, because the older I get, the more it seems to me that every person is like a separate universe.

Even, say, somebody like Nabokov, who would be so disdainful of anybody who was shocked by him writing about a fictional person that was a pedophile. Well clearly, Nabokov was a pedophile. His work is full of it. I don’t mean that he acted on it, but that he had this experience of Russia before the revolution as this magical paradise for him. He had this completely glittering, glorious view of the paradise of his childhood, and there was always like, a beautiful 12-year-old cousin. He had that going too, the incest part, as per Ada. He can act like the patrician who’s disdainful of the philistines, but no, people write from out of their own psychology. I think that’s true of anything I’ve ever written. It’s all autobiography in the sense you’re talking about.

Something that’s been a big frustration and disappointment to me in life is that for the longest time, I thought people could communicate with each other. I don’t think that anymore. [laughs]

AH: I’m curious about the part of the novel when Paul and T. are passing the typewriter back and forth, composing a poem line by line. Have you ever done that?

RH: Me and Verlaine wrote a whole book that way, sitting up late at night in like, 1971.

AH: Being street poets.

RH: Me and Verlaine would go over and disrupt open readings at St. Mark’s. We did that a couple of times. We were 19, 20 years old.

AH: For the hell of it.

RH: Because we were outsiders and we were mocking the people who didn’t include us. It was all ego but also youthful hijinks.

Probably the two scenes most true to my life in that book are writing the poem together and taking the walk uptown with the character Catherine. I wanted to do this kind of ode to poetry using the pattern of the relationship between those two 19th-century French poets, because it’s such an amazing story, the Rimbaud-Verlaine story. They were both complete bohemians. Verlaine was a total drunk derelict and Rimbaud was a provocateur, obnoxious fuck who gave up poetry before he was 22 and wrote great poems when he was 15. They were people who were just anti-convention—that’s what poets are like inside. Some of them are less so outside, like some of them take that Flaubert approach, where you have to live the most bourgeois life so that you can channel the transgression into the work.

AH: Were you reading Rimbaud as a teenager? He’s followed you for a long time.

RH: I bring it on myself…. I’ve taken exception to the way a lot of stuff that I’ve done has been attributed to some kind of fixation I had on Rimbaud, which is totally untrue. I did this whole novel using Rimbaud, so it’s kind of funny for me to say it’s totally untrue, but that came after the alleged fixation had already been established.

My French poets were Lautréamont and Baudelaire, both of whom come through translation a lot better than Rimbaud does. Rimbaud has a really wide range—his writing is so much more teeming and difficult than Baudelaire.

Rimbaud only existed to me as a symbol of the transcendentally-inspired teenage poet. I was probably 30 before I really started reading his work. I read his biography sooner than that and had his books, but they were hard to read. They don’t come through translation with anything like the immediate strength that Baudelaire and Lautréamont do. They were the poets I actually read; Rimbaud was more of a symbol of precocity and defiance and rebellion.

AH: It’s been written that your choice of the name “Hell” came from Rimbaud, from A Season in Hell, and that he influenced your look in the punk days, even your haircut. That’s wrong, though, isn’t it?

RH: He stood for something to me, but he had nothing to do with me picking my name whatsoever. Me and Verlaine had an idea that we would come up with new names for ourselves. For me, it was partly because I wanted everything about the band [Ed. note: The Neon Boys, later Television] to carry meaning. “Meyers” doesn’t mean anything. “Hell” means something.

I came up with that, then we had to come up with something for Tom. We both loved that whole series of poets in the latter half of the 19th century in Paris that hung out, and I suggested Gautier. That’s not so good I realized, because people would have a hard time pronouncing it, it doesn’t sound like it looks. So we’re scratching our heads, and Tom comes up with Verlaine.

It didn’t occur to me for a while that, oops, people are going to see a connection to Rimbaud because of his famous book A Season in Hell. But who knows about Rimbaud and Verlaine in rock and roll? It’s not going to be a thorn in my side. Nobody will misunderstand it except for maybe a few literary people, and there are not many in rock and roll. So I used that name despite Rimbaud, not because of him.

The hairdo was the other thing! I could give you the whole history of how that got misconstrued. It was something I scientifically approached and gave a lot of thought to and came up with in terms of the history of rock and roll, and had nothing to do with Rimbaud—but this kind of shit is inevitable. It makes you realize that everything you hear about history is a misrepresentation, because it’s what people tell you about what happened in the past because it makes interesting stories to them, they want it to be neat and clever, to fit their pedestrian minds, stories that make everything fit together. But things don’t fit together.

AH: What are you working on now that excites you?

RH: Do you know my book What Just Happened? That was my last big project, published in 2023, and since then I’ve been writing these personal essays for some reason.

In the pandemic, I started writing poems and I think of What Just Happened as a book of poetry. There’s a long essay, too, as well as notebook excerpts. It was gratifying to me because I’d never had a proper book of poetry before. My books with poems had all been sort of wide-ranging surveys—there was never some kind of consistent collection from a specific, brief, stylistically and psychologically integrated period, the way that comes naturally to poets.

I didn’t know what I’d be doing next and I ended up doing this thing that is kind of like a combination of writing fiction and writing journalism, being personal essays that are not about anything except what was on my mind.

An example is this long, bizarre thing that really made me happy about this experience I had after publishing that pandemic poem book, of reading a series of texts by other writers, my superiors, that immediately felt linked to my book as well as each other. Kafka, Joy Williams, Sebald, and Joseph Conrad—I linked those four writers to What Just Happened in a long essay that was really fun.

[Ed. note: Hell’s two-part essay, “Hooded Crow,” can be read on his site here: Part 1, Part 2.] ♦