Palestinians have endured displacement for the better part of a century. Today, for the tens of thousands of Palestinians from Gaza currently displaced in Egypt, Israel’s genocidal campaign has produced not only death at an unthinkable scale, but also the upheaval, loss, and destruction of Gaza’s world in all its forms, from the built environment to the families, communities, and livelihoods within. It is only the latest, if deadliest, chapter in a much longer generational history of Israel-inflicted catastrophe.

Since October 2023, over 100,000 Palestinians have evacuated Gaza through the Rafah crossing, often at exorbitant cost and with no guarantees regarding their future. Palestinian refugees in Egypt remain in legal limbo. Many of them lack passports and therefore are ineligible for basic services like public education. They lack the right to work and cannot open bank accounts. Their costly and hard-won legal status is provisional and could in theory be ended in an instant.

Egypt does not recognize Palestinians as refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention. Meanwhile, their counterparts from Sudan, Syria, South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Yemen, Somalia, and Iraq are broadly recognized in Egypt as refugees, and have rights that are conferred by that legal status. Palestinians displaced in Egypt are spared the starvation and perpetual bombardment that their friends and family in Gaza endure, but they still face crushing living conditions and precarious futures.

In May of 2025, I traveled to Egypt, where I met with families that had evacuated Gaza and been displaced since 2024. The common thread running through their narratives is that they feel they have no future in Egypt, given the anti-Palestinian policies of the Egyptian state. One family lives in Cairo, and the other lives in Alexandria. I share their stories below.

Most Gazans who have arrived in Egypt since 2023 live in Nasr City, a neighborhood in Cairo built during the 1960s under President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nasr City is known for its dilapidated infrastructure and unregulated high-rise developments. Although the neighborhood is crowded and unappealing for many of its residents, Palestinians who live there support each other through mutual aid initiatives, which often prove lifesaving, since most Palestinians in Egypt are legally barred from earning an income through work.

Both of the families whose stories I tell here have settled on the outskirts of Egypt’s congested metropolises in locations that are relatively more peaceful and better maintained than Nasr City. Yet, like nearly all Palestinians in Egypt, they have been waiting for over a year in a state of perpetual legal limbo, hoping to find out which country might permit them to make a new life for themselves.

Both families also reached Egypt the same way: by paying exorbitant fees to Hala Consulting and Tourism Services, a for-profit agency owned by Ibrahim al-Organi, an Egyptian business tycoon who has a monopoly on non-medical evacuations of Palestinians to Egypt. Although it is a private company, Hala Consulting has been granted an exclusive mandate by the Egyptian government to negotiate Palestinians’ legal status. Naturally, this system lends itself to corruption, and exploitative practices are rampant. Palestinians in Egypt reside there not only at the mercy of the domestic politics and priorities of the Egyptian state but also subject to the profit motives of a private corporation.

At the height of Palestinians’ exodus from Rafah, in April 2024, Hala was making $2 million every day from its “transfer” services. One father I spoke to told me that, due to a clerical error, his infant child’s name was originally left off the list of names of people who were permitted to evacuate. Had he not been able to bribe an official, it would have been impossible to evacuate his child.

Like the Egyptian state in general, Hala Consulting is broadly distrusted by Palestinians. The agency’s exorbitant fees and corrupt business practices indicate that it does not have Palestinians’ best interests at heart.

“We’re still waiting for a place to call home,” says Khaled Nasrallah, speaking from his temporary residence in Alexandria, Egypt. “We’re tired of moving,” he added, “tired of being displaced.”

Nasrallah, his wife Samah, and their six children managed to evacuate just before Israel closed the Rafah crossing in May 2024. Since then, the Nasrallahs have been trying to survive in a country that borders their native Palestine yet which has communicated through its hostile policies that they are not welcome.

I spent a few days with the Nasrallah family in Egypt in the last days of May 2025. Every morning at dawn, before the rest of the family woke up, Khaled would teach his youngest child and only son Nasr to read in Arabic. Five children were confined to two bedrooms.

After dawn, studying was impossible. As an immigrant without legal status, Nasr was not permitted to attend public school in Egypt, and the family lacked funds to pay for him to attend private school. This is a huge opportunity loss for the son. Khaled tells me that learning is “the only tool that enables our children to face the world and stand on their own feet! We know more than ever: education is the key to survival.” In addition to its negative impact on Nasr’s intellectual development, not being able to go to school deprives him of the chance to form friendships with boys his own age.

Khaled’s connections with Egypt long predate the 2024 exodus. It was here that he was born during the 1950s, while his father was working for Nasser’s government. His father worked as a driver in Alexandria for several years before he brought his family back to Gaza to raise them. Back in those days, Gaza was under Egyptian control, and the border was open.

Despite having been born in Egypt, Khaled knows he is not welcome now. Even he lacks the right to work, to open a bank account, to travel freely, to benefit from public services of any kind, or to reside in the country permanently. Like other Palestinians who have arrived from Gaza, his visa is valid for a mere 45 days. He must renew it perpetually, as if he were merely passing through the country where he was born.

Egypt does not follow jus soli (right of the soil, meaning birthright citizenship) like some countries, such as the U.S. and Canada. (The Trump administration aims to do away with birthright citizenship as well.) Only citizens have an automatic right to work in the country. Given this unfavorable treatment of an Egyptian-born Palestinian, one can imagine the hardships and persecution faced by other Palestinians who have found themselves displaced there.

In July 2025, Khaled reached out to me with what he hoped was good news. The French National Asylum Court (CNDA) had just made a landmark decision under the 1951 Refugee Convention to grant full refugee status to a Palestinian mother and her minor son from Gaza. It was the first time that Gaza residents not under the mandate of UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, had received such recognition in France.

Khaled hoped that this ruling would create a pathway for him and for thousands of refugees like him to find asylum in France, since Egypt refuses to provide a home for them.

I soon learned that Khaled’s hopes were misplaced. I reached out to the French Support Committee for Genocide Survivors (CNASA), which supports Gazan families that have arrived in France. Their response: “Contrary to what the right and the far right are trying to propagate, this decision only applies to Gazans who are already seeking asylum in France. Only the Ministry of the Interior, in conjunction with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, will decide whether to open the doors to Gazans who can submit an asylum application from Gaza or from a third country.”

The only Palestinians who stand to benefit from the French court’s ruling in the near term are those who have already found their way to France. In a political climate that is hostile to all forms of migration across Europe, it is impossible to conceive of a scenario in which France would suddenly welcome tens of thousands of new refugees from Gaza. Palestinians hoping for such a resolution to their legal limbo have to find a way to reach France first. Many of those who are determined enough to do so may die in the process.

Khaled summarized the situation simply: “So we have no hope.”

I remembered Khaled’s bleak words a few weeks later on August 1st, when France announced that it was suspending all evacuations for Palestinians fleeing Gaza following accusations that one of the students whom they had recently evacuated had made antisemitic remarks on social media. That was enough to furnish an excuse for the foreign minister not only to deport the offending student, but also to bar all other Palestinians from entering France. It was an astonishing act of collective punishment by a state that claims to uphold civil liberties and to respect the rights of the individual.

Before he left Gaza in 2024, Khaled Nasrallah had been a community leader. He was employed by UNRWA, the organization that provided humanitarian aid and support to a majority of Gaza’s population. Khaled was known by foreign aid workers and visitors as someone who was well-versed in the complex mechanics of aid distribution and from whom they had much to learn.

Prior to working for UNRWA, Khaled worked for Gaza’s short-lived Yasser Arafat International Airport. First opened in 1998, the airport briefly hosted commercial flights from Gaza to Amman, Cairo, and Cyprus until Israel bombed its control tower in 2001. The airport runway was bulldozed in 2002, bringing all service to an end. Khaled had worked in the airport’s logistics and transportation division. The skills he acquired during that work equipped him for many different tasks, including aid distribution for UNRWA.

While working for UNRWA, Khaled became acquainted with Rachel Corrie, the activist from Washington State who was killed in 2003 at age 23 by an Israeli bulldozer driver who was in the process of destroying a Palestinian home. The home that Corrie died defending belonged to the Nasrallahs. Corrie was living with them at the time as a volunteer for the International Solidarity Movement.

Khaled was the first person to find Corrie after she had been trampled by an IDF Caterpillar armored bulldozer. The driver was intent on destroying the family home, and even Corrie’s loudspeaker and bright clothing had not been enough to stop him. [Ed. note: Witness accounts and Corrie’s family have claimed that Corrie was in clear sight of the driver and was run over deliberately. An Israeli court ruled that the IDF was not at fault. See this 2024 Protean article by Laura Kraftowitz for more information.] Khaled raced to get her to the hospital, but by the time they arrived, she was already dead.

Corrie’s courageous resistance allowed the Nasrallah family to live in their home for a few more years—and yet, ultimately, the IDF succeeded in their aims, and it too was destroyed. The house, while it stood, was forever linked to Rachel Corrie and her sacrifice. Those who lived there would not forget her in the years to come. Khaled’s children, who were mostly too young to remember Corrie’s death, grew up with stories of her great heroism. The stories were told by his niece and nephew, pictured below with Corrie.

Khaled’s eldest child, Nour Nasrallah, was just a toddler when Corrie was killed. When she became an adult, she created a children’s book depicting the life of Rachel Corrie in honor of the 21st anniversary of Corrie’s death. The book, called I’d Rather Be Dancing, is currently seeking a publisher. Building on her expertise in animation and graphic design, Nour is currently working on a project that will turn the book into an animation. She dreams of eventually pursuing a master’s degree in film.

After years of struggle, Khaled managed to replace their destroyed home and move elsewhere. He was busy expanding their new home as a way of investing in his children’s future when Gaza became a war zone yet again.

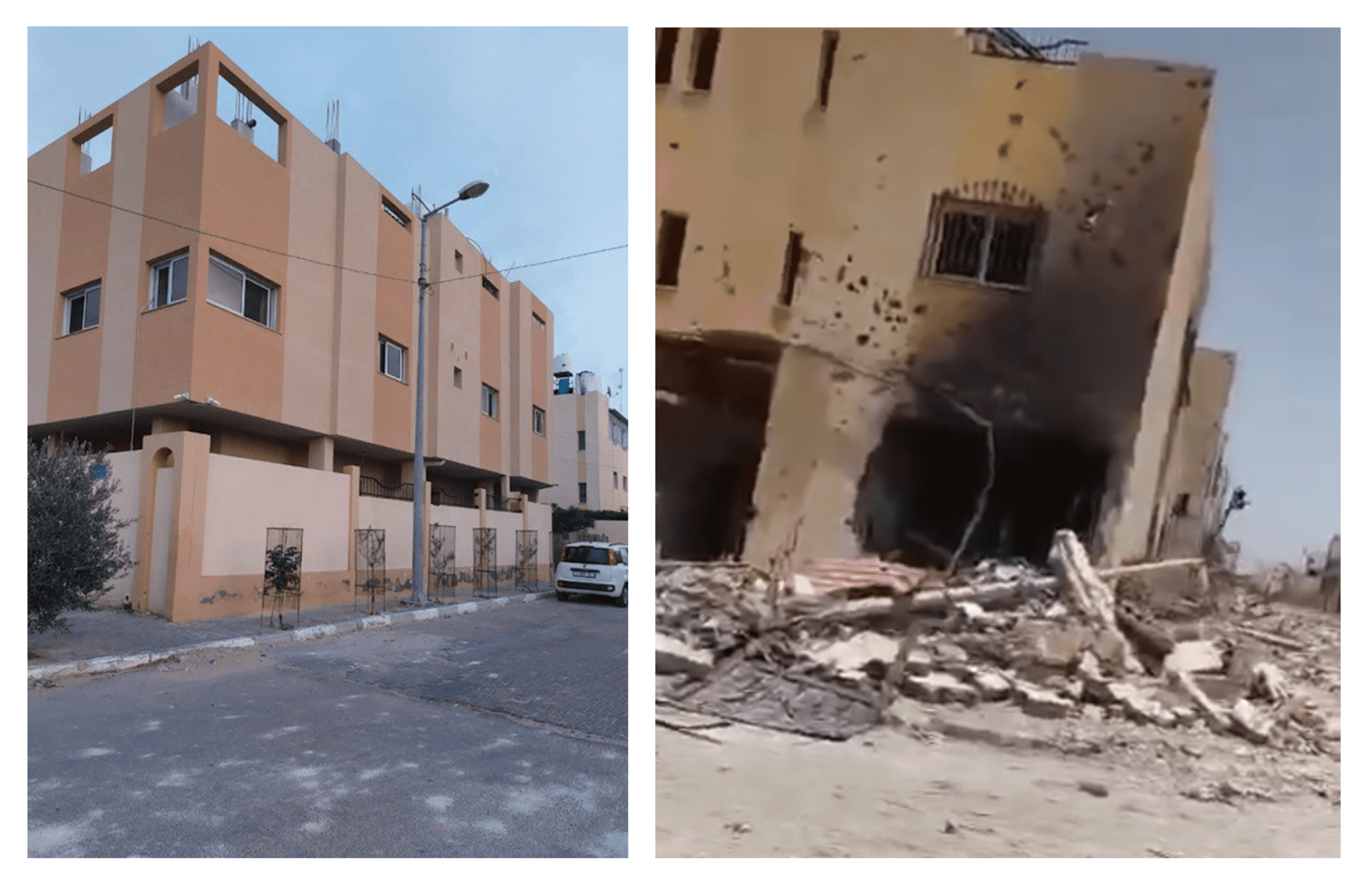

In June 2024, a few months after the Nasrallah family had evacuated to Egypt, their new home was destroyed by the IDF. One night during my stay with them in Egypt, they took me on a tour of Alexandria’s old city center. We sat down to eat, and Khaled’s wife Samah began speaking of their life in Gaza, explaining how much she missed it. She showed me the video footage of her home being blown to pieces.

I asked Samah how the video of the destruction of her home had reached her. She told me that the attack had been broadcast by the IDF itself on their social media channels.

“Will they compensate you?” I asked. The question was naïve, but I didn’t know what else to say.

“We were never compensated for the other times they destroyed our home,” she said flatly.

As has since been widely reported, the Israeli state compensates contractors to destroy homes in Gaza at the rate of 5,000 shekels (roughly $1,500) per home. Since contractors’ payment is tied to the number of homes they destroy, they are incentivized to destroy homes as quickly and indiscriminately as possible. One Israeli soldier recently told the Israeli newspaper Haaretz: “They’re making a fortune. From their perspective, any moment where they don’t demolish houses is a loss of money, and the forces have to secure their work. The contractors, who act like a kind of sheriff, demolish wherever they want along the entire front.”

Through such mercenary maneuvers, Rafah was reduced to rubble, and Gaza City is also now being destroyed. The Nasrallah’s yearslong efforts to rebuild were once again crushed by Israel’s genocidal agenda, one that is deeply intertwined with capitalist profit.

The Gaza Humanitarian Foundation first began distributing food on May 26th, 2025, the same day I arrived to stay with the Nasrallah family in Alexandria. Every night I stayed there, we would spend our evenings gathered together on the sofa, watching Al Jazeera’s footage of the Gaza genocide. We watched Palestinians lining up for food, scrambling to receive a small supply of boxes, and then being shot and killed as they fled.

The scenes were bloody, chaotic, and devastating. They would instill fear in anyone.The knowledge that I was observing the annihilation of the Nasrallah’s homeland as they sat beside me added another dimension of horror. The family watched silently as people they knew, or who were separated from them by a few degrees at most, were shot simply for trying to feed their starving families.

These massacres punctuated the daily rhythm of the Nasrallahs’ lives in exile. The incessant news of horror made palpable the fact that, even as they walked peacefully along the Alexandrian embankment at the edge of the Mediterranean Sea, genocide was taking place on the other shore. The world has not given the people of Gaza, even those who have been able to flee the crime scene, much hope for a stable future—let alone for a recovery that would enable them to reckon with their trauma.

Back in Cairo, I met with the al-Najjars, a family that evacuated Gaza just two months before the Nasrallahs, in February 2024. The al-Najjars were from Gaza City, in the north. Before the war, they had a beautiful home overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. Like the Nasrallah’s home, it was built from scratch, through labor that extended across decades. The family also had land, where sheep, rabbits, and lambs grazed among the olive trees.

The parents are now in their 70s. They have six adult children, three sons and three daughters. Since they have their own extensive families that could not be evacuated, the adult sons had to remain behind in Gaza.

The evacuation was organized by the eldest of the al-Najjar daughters, who lives and works in Europe. Having a family member outside Gaza helped greatly with the evacuation process; without her help, they might still be in Gaza. They left under fire, after their home had been destroyed and they had already been forcibly displaced to the south.

Yet as horrible as were the conditions under which they left, Nadia, the youngest of the daughters who was able to evacuate, tells me that she dreams daily of returning to Gaza. While in Gaza, Nadia had almost completed her training and was on track to becoming a successful doctor. Then her supervisor was killed overnight in an airstrike, and everything changed, including her dreams. “I will go back,” she says. “I will set up my own medical practice in Gaza and heal my peoples’ wounds.” The Gaza she knew was beautiful, and it will be again.

Having lived in Egypt for a year, the elderly al-Najjars now plan to settle permanently in Cairo. Their children will provide for them in their old age. Their eldest daughter has helped them find a home in their new city. A different fate awaits their younger children, who must find jobs to stay alive and to support their families. That means developing a plan for leaving Egypt and starting a life somewhere else in the world. The sons who remain in Gaza are likewise trying to find a way out—they hope to make their way to Egypt as soon as the Rafah crossing opens.

When the al-Najjar children leave Egypt, it will be Egypt’s loss, I think to myself. Wherever they end up in the world, they will carry Gaza with them everywhere they go.

Egypt has accepted over 1.2 million refugees from Sudan in recent years. The conditions under which they live are precarious, but, at a bare minimum, these and many other refugees in Egypt have been afforded legal rights. They do not have to perpetually renew their legal status without receiving any guarantees regarding their future. And yet this is not the case for the Palestinians that have fled there. The experience of legal limbo is a feature of the Palestinian condition, one that extends across the diaspora.

Various legal strategies have been deployed by the Egyptian state to deny Palestinians the rights of refugees. UNRWA, the U.N. agency tasked with supporting Palestinian refugees across Lebanon, Jordan, and occupied Palestine, has no mandate to work in Egypt. Without this mandate, they are unable to provide formal support to Palestinians.

Since they cannot be supported by UNRWA, Palestinians in Egypt should in theory be supported by UNHCR, which is charged with protecting all refugees around the world—but the agency cannot register refugees for this purpose without the consent of the Egyptian state. To date, they have not received such permission.

Despite the genocide on its doorstep, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi has repeatedly refused to open a humanitarian corridor to evacuate Gazans, on the grounds that doing so would further Israel’s mission of ethnic cleansing in the region . This is indeed their mission, as endorsed by President Trump in February 2025 and exposed to the world in an elaborate, genocidal plan that was leaked seven months later. And yet El-Sisi’s claim to this justification for refusing refugee access is spurious. El-Sisi has publicly stated that such a move would “liquidate” the Palestinian cause, while doing little to ease the lives of Palestinians within his borders.

While tens of thousands of Palestinians evacuated Gaza during 2024, the number of Palestinians who have been allowed to leave Gaza in 2025 is much smaller, just above 3,500. Evacuation is currently allowed only in rare medical emergencies. Israel has blocked the vast majority of these as well. Most Palestinians who need to evacuate, even for medical reasons, are left to die inside Gaza without access to medicine, food, or the medical equipment that might have saved their lives.

While Egypt’s resistance to integrating Palestinians into the Egyptian state apparatus may help to prevent or forestall further displacement, Egypt is by no means a benevolent actor for the Palestinian people of Gaza. As the second biggest recipient of military aid from the U.S. (the top recipient is, of course, Israel), Egypt may still be willing to participate in a future Nakba on the Palestinians if the price is right. We should not forget the extreme repression that participants in the Global March to Gaza faced at the hands of shadowy Egyptian paramilitary groups in June 2025, soon after they departed on their march to Rafah.

With their deep historical ties to Egypt and their shared language, religion, and culture, Palestinians could integrate well into Egyptian society if the Egyptian government permitted it. But the state prefers to keep Palestinian migrants in precarious circumstances.

While Israel perpetrates genocide on the Palestinian people of Gaza, neighboring Arab states watch passively, from Jordan to Lebanon, as if there is nothing to be done. Like their counterparts in Europe, Arab citizens are furious at the complicity and corruption of their ruling elite, which stands by as the Palestinian people are annihilated.

Around the world, ruling elites are determining the course taken by this genocide. They prefer that Palestinians live in perpetual legal limbo: denied a homeland, deprived of the right of return, and not allowed to settle and make a life elsewhere, even in a country just across the border. If we want to change the balance of power, we will need to let our leaders know that their complicity in genocide is eroding their legitimacy. ♦

First and second images: Nasrallah family fundraiser.

Third/cover image: Rebecca Ruth Gould, 2025.