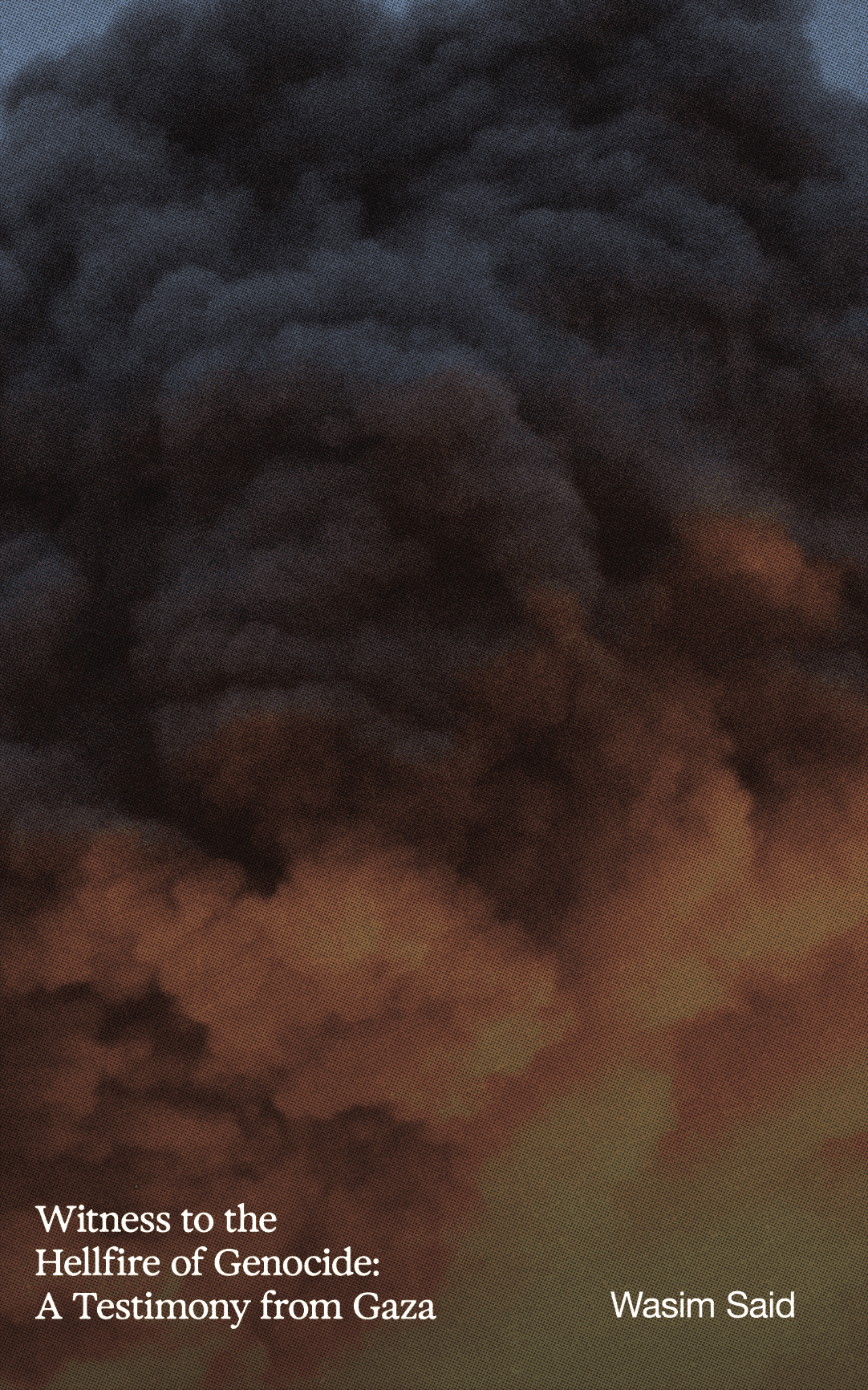

[Ed. note: This text is drawn from Mousa Alsadah’s foreword to the written testimony of a survivor of the genocide in Gaza. Wasim Said, writing as he fled the killing, recorded these stories of unthinkable horror and suffering. Said’s writings are being collected and published as Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza, forthcoming from 1804 Books.]

♦♦♦

Exactly ten years before his martyrdom by an Israeli airstrike—alongside his brother, sister, and their children: Alaa, Yahya, and Mohammad—Palestinian writer and academic Dr. Refaat Alareer wrote the following in the introduction to the book Gaza Writes Back: “The more savage Israel becomes, the stronger the reasons Gazans find to cling to life and to remain steadfast on their land.” Dr. Refaat continued, “Many in Gaza have sworn to fight in its defense; many others have sworn to protect the fighters’ backs. Some Gazans turned to their pens or keyboards, swearing to expose Israel’s aggression through writing.”

No one could have imagined the depth and extent of Gaza’s commitment to that vow—or how enduring the bond would be between escalating brutality and the will to resist it by every means possible, first and foremost through writing.

According to Israel’s logic, “What cannot be achieved through force, will be achieved through more force.” But what brutality remains to be unleashed on a people beyond genocide itself?

Yes, we must be cautious not to romanticize resilience—to avoid masking the scale of the tragedy, injustice, betrayal, and complicity by exporting the image of the invincible Gazan hero, as though they are anything less than human. Too often, we indulge in the fantasy of heroism as a way to ease the shame of our failure to stand with them.

Forgetting that before they are heroes, they are oppressed—utterly isolated, in a loneliness unlike any before. That is why before we weave our relationship with the hero, we must weave it with the oppressed. The former offers a false comfort; the latter demands action, discomfort, and a call for commitment to fight for justice. These two Hero/Oppressed definitions do not cancel each other out—but we must understand: these heroes are, first and foremost, oppressed. “The wretched of the earth,” in Franz Fanon’s [sic] terms.

Exactly one hundred years ago, Zionist theorist Vladimir Jabotinsky wrote his infamous article “The Iron Wall,” declaring that “[Arab people] make such enormous concessions on such fateful questions only when there is no hope left. Only when not a single breach is visible in the iron wall,” Yet, this book stands as hope itself. It is one of those cracks.

Written by an oppressed hero under such extraordinary circumstances, this book proves that Jabotinsky, and every Zionist theorist after him, were wrong. And it reaffirms, once again, that Dr. Refaat Alareer was right, as it offers a living answer to the vow Dr. Refaat spoke of.

Genocide embodies the most intense form of concentrated death and mass killing against the human race. While the literature on genocide often emerges after the fact—through survivors’ testimonies—this text documents it as it happens. Zionist warplanes soar above it, their drones hum nearby, while the pen and paper seek refuge beneath the cloth of a displacement tent, writing in the shadow of hunger and famine.

The writer did not retrieve these moments from distant memory; he lived them, moment by moment, as he wrote them. This was not writing about death, but writing within it, surrounded by it. And this is what the reader must first understand: every scene recorded here, every scream, every shelling, was not merely a subject to be written about—it was a living reality invading the act of writing itself. The very process of documentation cried out for its own documentation. This foreword is merely a humble attempt to cast light on that.

So when you read, do not overlook the sound of warplanes, the explosions, the sirens—they still pierce through every line and slip between the words, because they are, quite simply, part of the text itself.

In late April, my friend Louis Allday sent me the first draft of the manuscript, along with a note: “You must read this—and we have a duty to help publish it.” That was the beginning of my communication with Wasim. In the very first voice note he sent me, Wasim shared his reasons for writing this testimony. His motivation reflects the inner thinking of a person besieged by an unbearable magnitude of death—its multiplicities, its fractures.

He spoke of resisting the collective erasure of families, of entire lineages being slaughtered. He refused to let them vanish into oblivion. Someone had to give them meaning, to preserve their memory. And that is what Wasim took upon himself.

But Wasim didn’t write after surviving. He wrote from within that narrow corridor of life amid the crush of massacres. And in every message and recording between us, he repeated: “My aim is to leave a mark” and “not to be forgotten.” This text is his personal answer to a question that haunted every Gazan: Will I die and be forgotten? Will my death pass as though I never was? Or as one person bitterly put it: “If I’m lucky enough to be martyred, to be wrapped in a shroud, to have a funeral, I’ll be remembered for two hours, then it’s over. As if I never existed.”

Wasim wrote to break that forgetting—to give those who left a trace, and those who remained a sense of solace: that someone had witnessed, had recorded, amidst death, that they were here.

And here, precisely, lies Wasim’s courage. In this act, he may have embodied the very courage of Gaza. A young man in his early twenties, rebelling against an imposed end, refusing to be erased in silence. In a moment that might be the most harrowing in human history—a death that’s wide-scale, technologically advanced, and globally enabled—Wasim wrote, with nothing but paper and pen.

He spoke to me at length about his moments of doubt, moments when he questioned the meaning of it all. He nearly surrendered to despair, almost stopping many times. But he carried on. For Wasim, writing wasn’t just expression; it was the physical act of answering the most philosophical of questions: What does it mean to live? For him, meaning wasn’t abstract—it was action: If I do not write, it is as if I never lived.

And because he is Gazan, Wasim’s answer was never an individual escape, never selfish; it was collective. In the text, you see him hesitate, embarrassed even to speak about himself, and he asks: What about my community? What about those who never got the chance to write? Soon, the text becomes theirs. He wrote on their behalf in one of the noblest forms of self-sacrifice, following the steps of his brothers and sisters of the Palestinians fedayeens, or resitance fighters. Wasim did not carry a weapon. He stood, with his pen, in their place.

This collective spirit flows through the text, just as it flows through Gaza in the solidarity of people under genocide. Genocide, as a concept, is not merely mass killing. It is a systematic colonial process aiming to dismantle the colonized society, its material structures, institutions, and self-organization. But at its deepest level, it aims to destroy the moral structure of that society, to fracture it into scattered individuals, each preying on the other to survive.

And here arises this testimony—not only as a daily record of generosity, selflessness, truth, and cooperation, but as proof, in itself, of an astonishing resilience in the moral structure of this community under genocide. This, precisely, is what anthropology must learn from Gaza: that despite the magnitude of the genocide, despite Zionism’s belief that its policies would produce a society the reflects its own monstrous image, the moral fabric of Gazan society has remained remarkably intact, even as long as the genocide has continued.

This does not mean it went unshaken. Yes, a segment of exploitative traders emerged. Organized crime harmed people just as the occupation did, and Wasim speaks painfully of his encounters with them. But total collapse never happened.

This society held onto its image of itself: its Palestinian and Arab identity, its moral and cultural system. A significant part of it refused to let go, as if echoing Wasim’s search for the meaning of life, but at the scale of an entire people, the Palestinian people.

The enormous toll of death left its mark on Wasim. Everything became urgent, rushed, as if life itself were narrowing fast. He was literally running, Zionist death chasing behind. He pleaded with us to hasten the book’s publication, unsure whether he would live to see it. I would ask him what he had to eat while writing, in the height of famine. He would reply: a disk of bread made from ground lentils, or a bit of rice.

Still, Wasim endured. He wrote, not only to survive, but to awaken a duty within us.

This testimony, with its clarity, logic, and living embodiment of the intellectual’s role—and of culture’s power as long theorized by philosophy—is not merely a document. It is a message from the deepest depths of the valley of death, from the hellfire of genocide, to the Arabs and to all of humanity. A message that says: death, even on this scale, did not strip Wasim, and did not strip Gaza, of their value system. They did not relinquish dignity, courage, effort, solidarity, pride, nationalism, or resistance.

And so each of us is faced with the great moral and national question: we, from within our lives of comfort and consumption—what is our excuse? ♦