This article appears in our fifth print issue, Contra Temps, available here.

♦♦♦

In 1931, the young Slovenian-Yugoslav painter France Mihelič returned to his parents in Ribnica by train, seeking work, his long sojourn to the south having come to an end. He had sought work, and an education, but was now beholden to a very different future. Between his feet, he carried a wicker suitcase and his lithographs and woodcuts, all bound up neatly in a portfolio. It must have felt strange to carry his body of work around, both in his grip and in his psyche: Mihelič was heading home after serving his first stint in the army, nine months among the ranks of the already-flailing Kingdom of Yugoslavia, months so miserable and full of torment he drew himself on the latrine with a gun under his chin, trapped in the interregnum between intent and suicide.

Things had not been not much better at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, the only art school in his whole country, where Mihelič had lived in a collective hovel, laboring over medical illustrations of dead fetuses and deformed genitals for a lecturer in obstetrics. He bore this grim employment out of the need to feed himself—until, according to an essay by his daughter Alenka Puhar, he lost the job after cracking a smile at an inopportune moment.

Still, his career was not entirely free of glimmers of hope; it was during this time that he won some occasional small commissions, some acknowledgment from the old generation of Slovene artists—among them Rihard Jakopič, the leading Slovene Impressionist and a staunch advocate of the art of his countrymen, who had blessed our tired young man by selling a handful of Mihelič’s prints in Ljubljana. But none of it was enough to live on. Heading home empty-handed seemed, in a time of global desperation and high unemployment, perhaps inevitable. Lots of people in the 1930s boarded trains wondering about the days to come, and whether there would be any bread for them.

Mihelič wasn’t the only artist grappling with the harsh realities of the time, materially or artistically. When he was in Zagreb, the influence of the Marxist art collective Grupa Zemlja (“Earth Group”) was strongly felt. Formed in 1928 as a reaction against both Impressionism and a resurgent neoclassical traditionalism, Grupa Zemlja was concerned above all with alternative materialist modes of artistic production.

As their manifesto put it, “An artist cannot escape the needs of the new society [novoga društva], cannot stand outside the collective. Because art is an expression of looking at the world. Because art and life are one.” Zemlja’s most famous practitioner was the painter Krsto Hegedušić, whose colorful yet unsettling scenes of peasant life and thematically complex depictions of poverty diverged from other developing styles of social-critical painting, such as the more neotraditional strains of socialist realism popular in the USSR. Yugoslav authorities banned Zemlja in 1935 as a part of a broader crackdown on socialist organizing.

Mihelič, at the time, was studying at the academy, where one of his teachers was the muralist Maxo Vanka. The latter would introduce Mihelič to Brueghel (who was both Vanka’s and Hegedušić’s muse), and by extension to medieval art in general. Seeing the plight of his poor student, Vanka also hired Mihelič to assist him with a commission preparing painted glass for a church. Like the Marxists of Zemlja, Maxo Vanka was a known and devoted socialist. Shortly after he taught Mihelič, Vanka would emigrate to the U.S., where he became a close comrade to the Slovene-American muckraker Louis Adamic, author of the book Dynamite: A History of Class Violence in America. Vanka’s murals in the St. Nicholas Croatian Church in Millvale, Pennsylvania remain in place today as powerful anti-capitalist and anti-war statements that mingle the medieval with the modern crimes from which mankind still needs salvation.

Mihelič’s later anti-war work, his color woodcuts of the traumatized war-witness and his pastel triptychs of bombed-out landscapes, would pursue an analogous thesis of subtle medievalism and contemporary political struggles, albeit in a more conventionally modernist language. This was the early milieu in which Mihelič traveled, along with his fellow students. Stylistically, it shows: one of his earliest post-university works is a lithograph of himself starving to death, mouth open, feet splayed helplessly across a straw mattress. The lithograph Pozabljeni umetni (Forgotten Artist), is rendered with special attention to the texture of reeds, of earthiness. Its subject is social, its purpose critical—and its style is neither socialist nor expressionist, but somewhere in between.

When Mihelič took his first steps off the train in Ribnica, the first person he saw might well have been his father, who worked in the railroad depot. Mihelič would draw many variations of his father in this setting: the same expectant, weary man in his cramped workroom heated by a coal-fired stove. In these depictions, each iteration of the figure disintegrates further into distressed grief than the last. Like most poor people, Mihelič’s parents moved often. France, the fifth child of eight, was born in 1907 in Škofja Loka, a fortress town in the shadow of the Alps. Mihelič grew up in the nearby village of Virmaše, where as a child he enjoyed spending time in the forests, hiding in the hollows of trees, collecting rocks and sticks, observing the quiet pageant of organic matter—his earliest experiences of what would become an enduring fascination with, and fear of, the processes of living and dying.

These times were also happy ones, as Mihelič would attest in his own words—carefree, in the way that children who are allowed a degree of tethered freedom often are. In later years, work would send the family south, past Ljubljana—where Mihelič, before fully embracing and nurturing his drawing talents, had first studied to become a teacher—and into Dolenji Lazi, a town consisting of little more than 240 people and the railroad line that sustained them.

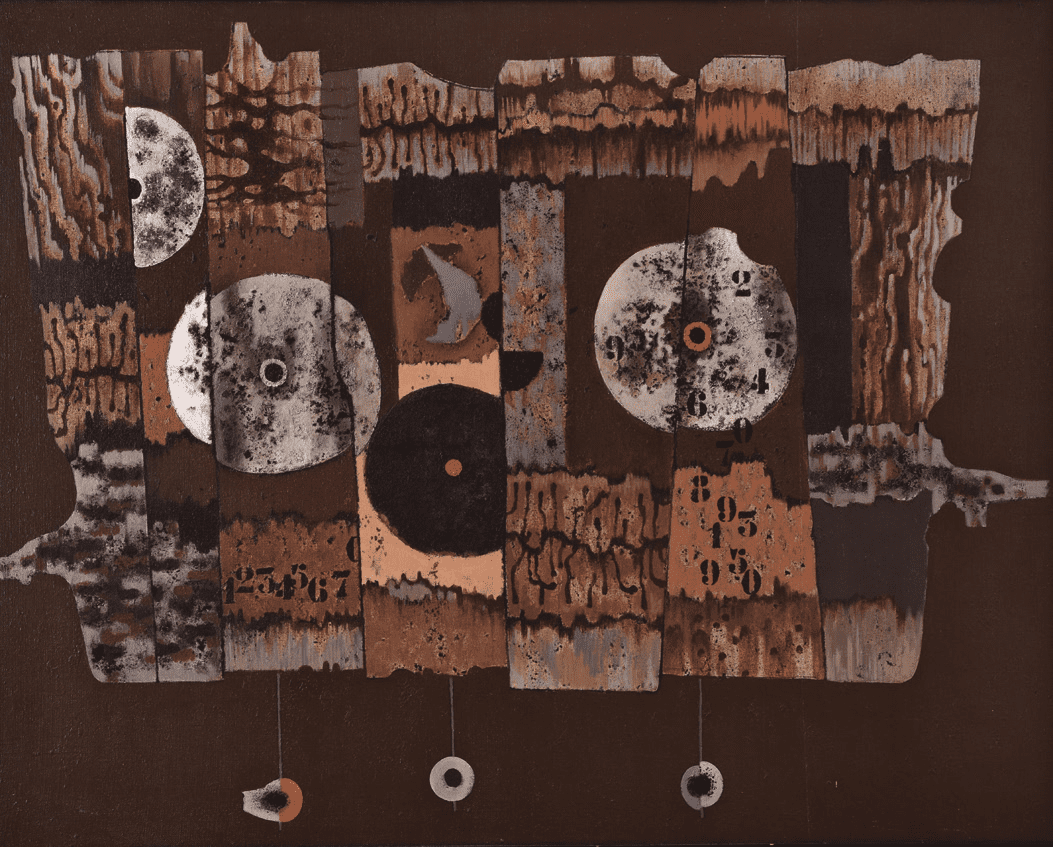

There, the young man gathered his few belongings and walked to his parents’ tiny house. He resolved that, while living with his parents, he would try to lessen his burden on them. In the barely habitable attic, he built himself a studio. In the studio was a bed, a nightstand, a kerosene lamp, his supplies, the wicker suitcase he came with, and whatever it contained. In order to mitigate the bleak abjection of this setting, he put some flowers in a clay vase, hung a broken clock on the wall. In lieu of windows, which the room lacked entirely, he tacked up some of his old student work, which gave the room a strange forced perspective.

He would go on to draw this same wretched room over and over and over again many different styles, full of many different apparitions and visitors. When not explicitly depicting the room, he would often make visual reference to its rotting textures and disintegrating walls, or its contents: lamp, flowers, easel, suitcase, clocks. Without this room, this skeleton key to understanding the rest of his oeuvre, there would be no France Mihelič as we know him. The room was both a place he sought to escape, and as much a part of him as his own skin—the stage of his psyche, as viewed from behind the curtain.

To borrow from my translation of Puhar’s essay:

When he knocked together all those boards that gave the attic the appearance of a chamber—something that looked like it would be taken from the stage of a… realistic drama—when he emptied the wicker suitcase and pushed it under the bed, when he put an easel in the corner, a kerosene lamp on the bedside table and collected flowers so that everything would have a touch of domesticity, when he had done all this, he could start to draw, draw this same chamber, huddled under the roof, draw the same wicker suitcase and kerosene lamp and the bed and the shoes shoved under it, flowers in a clay vase and a broken clock, the easel and the forces of anxiety. And himself in this cell.

In these pages are six artworks by France Mihelič, painted in the 1970s, 40 years after he stepped off the train in Ribnica. From January through March 2024, these paintings and many of his other works were on display at the Bežigrad Gallery 2 in Ljubljana, in an exhibition called “Nekoč” (“Once Upon a Time”). The pictures that are reproduced here have their origins in that room, and in the conditions of impoverishment that made up the substrate of Mihelič’s life at this time.

Because the exhibition was free, I went every day I could. I would sometimes stand there for hours, writing in the little black notebook I carried with me. The paintings seemed to induce rambling, bizarre thoughts. At the gallery I began to experience a strange sense, one that would only intensify with each new visit: that we—France Mihelič and myself—somehow knew one another. This is, of course, not rational; in fact it is a little embarrassing.

And yet I increasingly believed that if I could look into Mihelič’s solemn figures and contorted dreams long enough, I would come to understand something elusive about not only myself but about matters far beyond my solipsistic confines. I had the overwhelming sense, rational or otherwise, that these images contained matters of great metaphysical importance—matters, as they say, of life and death.

By the time I’d gleaned the full story of Mihelič’s life—which came only at the end of my journey—I had been attending so closely to his work, filling my waking life with his paintings, that I felt I had come to know him too. Some of my inferences were, I discovered, not far from the truth. After pointedly deploying the word “critic” to win myself a private tour of the Mihelič Gallery at the Škofja Loka Museum, the curator Boštjan Soklič spoke about having known Mihelič personally. While listening to stories of the real France Mihelič—and learning that, just as I’d imagined, he was an ironical, politically fraught, private, pained, and inquisitive person—I became so eager and excited that I probably seemed less like a “critic” and more like a naïve fan.

But, before those crucial revelations, I looked. In Ljubljana, I looked. In Škofja Loka, I looked. In Ptuj, I looked. The more I looked, the more I needed to look—and so the cycle went. Mihelič’s world gradually became mine. He lived in the black soil and the dark grain of hardwoods, in the mildewed cloth wrapped around a balcony that I saw from the streets of Ljubljana, in the faces that began to appear in the bark of the dead, contorted trees in the courtyard of my apartment building. Being in

the repeated presence of the same works of art is a special form of conversation, a relationship that complexifies with time. (Which is another reason why visiting galleries should be free.) If you spend enough time looking at a body of work, you will come to feel that not only do you know it, but also that you are known by it, and known deeply. This is a sense that extends beyond a purely aesthetic engagement with art; it is not necessarily pleasurable. In fact, I often found it intensely unsettling.

Freud would call this kind of mutual recognition—one that extends across time, beyond death—“the uncanny.” But I find the thinking of Walter Benjamin to be the better touchstone for demystifying this process. Benjamin referred to the sense of familiarity one gets from art as the aura. “Experience of the aura,” he wrote in his essay “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” “thus arises from the fact that a response characteristic of human relationships is transposed to the relationship between humans and inanimate or natural objects. The person we look at or who feels he is being looked at, looks at us in turn. To experience the aura of an object we look at means to invest it with the ability to look back at us.”

And so, impossibly, France Mihelič and I looked at one another. My initial studies of him were mundane: I would write little notes about each work, mapping out conceptual linkages, jotting down scattered thoughts like “In his early village drawings, Mihelič makes no distinction between the structured mottled appearance of brick and that of the soil, the earth, of shadow, of filth and age.” But by the end of my first day in the gallery, I had already been transported elsewhere. By then, I had already written: I am looking at something that sees.

The medieval town of Ptuj is a captivating and unnerving place. Its ribbons of narrow, winding streets are pinned between the fat green swell of the Drava river and Ptujski Grad, one of the most impenetrable castles of the Middle Ages. Here, Mihelič, after finding some career footing by illustrating the socialist poems of Mile Klopčič and participating in small exhibitions in Ljubljana, began to teach. First, he took a temporary post in Kruševac, Serbia, which he soon came to resent—until, to his relief, he was transferred back home to Slovenia.

In 1936, Mihelič was appointed drawing teacher at the Ptuj grammar school. He undoubtedly walked the path that runs from the train station, past the Minorite monastery, and into the main square—a path I myself would walk hundreds of times. The town square is framed by a gingerbread theater from the 1800s and the careworn facades of Baroque buildings. There, too, Mihelič must have stood, watched over by the tripartite guard of the castle, the Baroque-topped town tower, and the 13th-century Church of St. George.

Such teaching positions held prestige, and were few and far between. For the first time, Mihelič had money in his pockets. He went abroad on short jaunts, wrote some rather scathing dispatches on the state of Western art; he was especially unsparing about the stolid offerings of Spanish artists under Franco. It was at this point in the late 1930s that many of the Slovenian artists who studied in Zagreb were beginning (as every generation does) a process of individuation, seeking ways to distinguish

themselves from their teachers and forerunners.

Mihelič’s generation was no different: many of the likeminded would form the politically liberal Klub neodvisnih slovenskih likovnih umetnikov, the Club of Independent Slovenian Artists. Despite their allegiance, they were all aesthetically distinct. The Club of Independents’ goal, as art historian and now-Minister of Culture Asta Vrečko noted in her paper on them, was to establish a specifically Slovenian trajectory for the future of art. They sought to organize exhibitions and use the press to drive public engagement. In this they were both successful and popular. However, perhaps out of the desire to assimilate into the existing culture industry, they seem to have tempered any radical ambitions to politicize the movement or use it as a basis for collective action.

Meanwhile, Mihelič was painting prolifically. With the benefit of an income and the use of a spare storage room at the grammar school, he was freed to pursue a stylistic evolution. Works from this period were often big, moody, color realism scenes depicting religious pilgrimages to Ptujska Gora under darkening skies. Ptujska Gora was home to a famous medieval statuary workshop that fascinated Mihelič. It was in Ptuj where the artist first witnessed the most famous autochthonous Slovenian carnival tradition—long-preserved in local practice but later officialized (with help from Mihelič himself) in the 1960s—known as Kurentovanje.

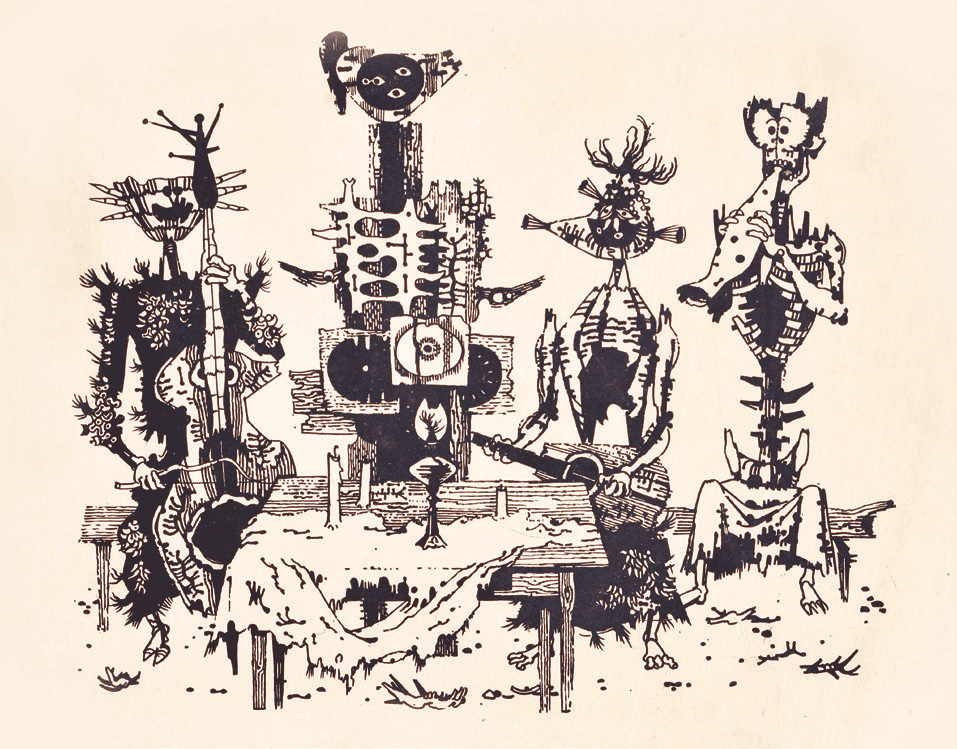

Kurentovanje takes place during the Shrovetide season, i.e., the time of the year before the beginning of Lent. Kurent (pl. kurenti), Mihelič’s most famous subject, is a pre-Slavic folkloric man-spirit specific to the region around Ptuj. Those who have not seen kurenti in real life may find them difficult to picture—they present a baffling figure. When a person, traditionally an unmarried man, dons the sheep-skin, snout-nosed, bell-waisted, feather-eared (or horned) costume of Kurent, he ceases to be human. He becomes something bestial, primordial, and primeval, with his hands and feet the only remaining signs of his humanity. Kurent, accompanied by a menagerie of parading characters—each with their own narrative roles and equally complex symbologies that represent facets of traditional village life—is tasked with scaring away the winter using his frightening mien and the jangling bells around his waist.

Despite his appearance, in the folklore, Kurent is less a monster and more a god: in some stories a trickster, in others a hedon. What remains consistent is that he invariably symbolizes virility and rebirth. Mihelič sensed the underlying eroticism of Kurent, whom he would later pair with images of Daphne, the naiad of Greek myth, with the latter depicted in disturbing and subversive nudes. But more relevantly, as Milček Komelj addressed his book on the role of Kurent in Mihelič’s art, the

painter understood the catharsis, subversiveness, and indeed the violence of these festivals as a metaphor for the simmering brutality girdling the whole of Europe, from the Spanish Civil War to the ascendant fascisms of neighboring Italy and Austria.

Kurent served as an important expression of Mihelič’s central themes: the dialectic of life and death, and, by extension, the synthesis found in transformation. After having witnessed the death of a farmhand dressed as Kurent, Mihelič painted, in Mrtvi Kurent (Dead Kurent), the piteous scene of carnival-goers gathering around the collapsed bringer of spring. In the painting, the great spirit is extinguished—demythologized and re-rendered as a fallen man. This was material that he would relitigate in countless renditions, in new stylistic permutations. The grim painting would also prove a harbinger for the end of Mihelič’s own spring. His happiness in Ptuj was short-lived: in 1939 his wife died young. In 1941 he would board a train for Ljubljana to join the Partisans.

Throughout the struggle for liberation, Mihelič—while under the constant threat of the enemy, huddled under debris, crouched among ruins, in forests, on long marches through the snow—would draw. He would draw on anything he could find: pieces of detritus, old sheets of linoleum. The linocuts from the collection Our Struggle (Naša Borba), which he published with Nikolaj Pirnat, a fellow member of the Club of Independent Slovenian Artists, are not only remarkable as a work of underground socialist agitation, but also as an indicator of Mihelič’s lurking medievalism. The compositions more closely resemble El Greco paintings or stained-glass windows than anything modern. Rough-cut scenes of death surrounded by cruciform trees, vile and grotesque depictions of crooked-toothed Nazis, the horror of bombed-out villages, the quiet strength of an isolated Partisan camp—these were renderings of a collective yearning for freedom, finding purchase in the young artist’s emerging and broadening imagination.

During the war, these tender, forceful images were displayed in small, clandestine exhibitions in liberated forests. The ideology of these artworks is explicit, and they were shown with a specific purpose in mind: to attest to bravery in the face of despair, and to inspire the resistance to carry on. As the art historian Gal Kirn writes: “[They] seemed to be one of the only ways of bringing back the whole of human dignity in those most brutal times.” The war blew open Mihelič’s horizons, and his psyche. Death, his old specter, became more real than ever. He would spend the rest of his life chronicling and artistically interpreting the atrocities he witnessed, using his art to process the senseless, visceral horror.

After the war came both political and interpersonal friction. Mihelič, haunted by his experience of war, believed art should be inherently anti-militaristic. Unsurprisingly, he disliked much of the patriotic socialist campiness of the time. Yet neither did he feel that he could return to his old color realism. His mind, like those of many of his contemporaries around the world, had been reshaped by a conflict that

represented the violent apotheosis of industrial modernity. The immediate aftermath was also a fraught time for Yugoslavia, owing to the Tito-Stalin split and the resulting vicious paranoia that characterized the Informbiro period. By the early 1950s, in part due to these political developments, socialist realism had lost its stranglehold on art. Meanwhile, the country itself finally began to stabilize and industrialize, embarking on an extended campaign of construction and modernization. Entire cities seemed to rise from the earth, every little kitchen stocked with new Gorenje appliances.

Yugoslav socialism, flawed as it was, held the door open for Mihelič. His career opportunities broadened, and he began to travel for long periods. Most notably, he spent 10 months in Paris in 1950, when he was 43. There, he was influenced less by the prevailing Western bourgeois art (his youthful New Objectivist explorations were anti-expressivist, and he never even dabbled in Abstract Expressionism) than he was by the exotic animals at the zoo and the museums full of Neolithic statues and relics from far-off places. These he drew in loving detail.

Around the same time, he also discovered the work of the painter-poet Henri Michaux, whose absurd, ironic fantasies were depicted explicitly, in deliberately contrived scenes, distinguishing Michaux from his Surrealist contemporaries. While Mihelič did make a turn to a surrealism of sorts, he did not draw from the usual wells, like the subconscious or divined dreams. Rather, he returned to his longtime fixation on the biological, the stuff of life: moss, trees, moths and other insects, frogs’ eggs, cocoons. These lucid visions, broadly labeled “Fantastic Art,” found immediate success abroad, winning him spots in the Venice and Sao Paolo Biennales and at the Yugoslav galleries in France. Shortly after his trip to Paris, he married the writer and translator Mira Mihelič, with whom he lived until her death in 1985.

Meanwhile, at home, Mihelič prospered in Yugoslavian art and academia. He received lucrative commissions for everything from murals to illustrations and was made one of the inaugural instructors at the Ljubljana Academy of Art. This newfound material security allowed him room to experiment. Once he’d pursued and tested new aesthetic directions, he could then apply what he learned to past fixations: Kurent, his father, the room. His became a unique oneiric language of flying apparitions, fairytale monsters, folkloric beings, and surreal scenes, all of which had germinated from those leery, earthly forms rendered in loving charcoal so long ago. He could, for the first time, dream unhindered.

But while Mihelič himself would flourish, for his country, prosperity would prove short-lived. Mihelič continued teaching and working during the late 1970s and 1980s, a time of global recession and unrest that presaged the unraveling of communism. As Mihelič got older—he would retire from the academy in 1970 at the age of 63—the more he looked inward, seeking the universal in the personal. This period comprises the paintings reproduced in these pages: paintings of old apparitions, of the room in Ribnica, of objects like clocks and doors that had long haunted his psyche.

Of these, Ure, painted in 1972, is the most powerful. At the gallery in Bežigrad, I went to visit this particular painting around two dozen times. On a gritty field with a smoke-like texture, clocks and their numbers transform into a spindly apparition crowned with motifs that resemble burnt-out fish traps. The sandy, ashen tonalities impart a sense of motion; they gesture at the appearance of life extinguished. To my eye, they contribute to the uncanny sense that a sight much like this one may well be the last thing we see before we die.

It’s as if the painter, a man terribly afraid of dying, proceeded so far in his fixation on death that he was able to glimpse it and render it, making it the very material he worked with. I became afraid that if I got closer to the painting I would smell the residual scent of burning. That he painted these paintings at the apex of Yugoslav socialism, almost in anticipation of its fall, is perhaps no coincidence. What better time could there have been to tackle the big existential questions, to examine the plight of human frailty, than during the last decade of comfortable prosperity, of material freedom?

It’s my own hope to live in a society in which everyone prospers. Even if this world comes about, suffering will, of course, never be fully eradicated. But in a fair world, any of my suffering would be truly my own, and not the imposition of a cruel order. I wish, like Mihelič, that I could take the time to return to myself and my own humanity as a project. But before that can happen, we must build a world that supplies the security and space for us to take up such concerns, to turn our full attention to that work. Yugoslavia, however imperfectly, did provide that to Mihelič, and to many of its artists, for a time.

When the paintings you see here were made, as Katja Praznik notes in Art Work: Invisible Labor and the Legacy of Yugoslav Socialism, the old bourgeois order of art as being spiritually above and therefore different than work had prevailed in the attitudes of Yugoslav officials, who had become themselves a kind of bureaucratic bourgeoisie. Politically, Mihelič himself walked that questionable line, struggled with the dichotomy—of art as, on the one hand, something exalted and spiritual, requiring a special kind of inherently personal vision and talent—and the artist as (an often impoverished) worker on the other. The latter was a reality he also knew well. But soon, for Yugoslavian artists, the question of locating oneself within that dichotomy itself would be moot: by this point, the market was allowed to penetrate the formerly planned economy.

The oil-induced economic stagnation that strangled the West hit Yugoslavia particularly hard, as their economy relied heavily on imports, especially of oil. Loans from the IMF and World Bank ballooned into an existential debt crisis. Tito died in 1980. Mihelič’s friends and contemporaries were all aging. His collaborator Nikolaj Pirnat had died long ago, in 1948; with time, the people important to Mihelič, his wife, friends—and fellow artists—would die too. And then Yugoslavia itself was gone, ended ignobly in a genocidal war.

Mihelič, lonely and old and not without some bitterness, would later tell the young writer Milček Komelj that he was left “without a real society dedicated to art.” He died in 1998. “Time is an enemy,” he once said. Looking at his life, at the poverty and privation, peril and courage, disappointment and obsession, he had every right to say it. I can’t look at the pictures without thinking of him.

Hanging in the Mihelič Gallery in Škofja Loka are a few photographs of the artist: at work, drawing, sitting in a chair by the banks of a river. He had a 20th-century face, clean- shaven with a strong chin. He wore his hair slicked back. Holding his tools were the hands of a workman.

“What was he like?” I asked Soklič, the gallerist.

“As a man, he was funny,” he said. “He liked irony. Sometimes it got him in trouble. But when he worked he was very serious. Work made him happy. And when he worked, he always listened to classical music on the radio.” Hearing this, I felt a deep affinity, as I had so many times in learning about Mihelič.

“It must have been unbelievable, really, to have lived through the whole 20th century like that,” I said. “Imagine, being born at the tail end of the Austro-Hungarian empire, fighting for socialism, and dying in an independent Slovenia.” Soklič glanced at me grimly. He was perhaps in his 60s and had the appearance of someone permanently needing a smoke. “Yes,” he sighed. “Now we are all slaves to capitalism.”

Later I asked him what he thought Mihelič’s paintings were about.

“Grief,” he answered, as though it were obvious. He added, “You know, it’s good that an American is writing about Mihelič. Slovenians don’t like him very much.” I don’t blame them. For all the laudation of Mihelič as a national artist (as opposed to a Yugoslav one) the portrait he paints of his homeland is rarely pleasant. It doesn’t fit in with the goals of the tourism industry or the plucky, self-assured, newly independent, market-optimistic image today’s Slovenia wants to show to the rest of the world. Mihelič looked at his country and saw what was ugly. He saw a violent, small-minded, and superstitious place burdened with death and fear. But it was his place nonetheless. At the heart of his criticism is an obvious, almost uncomfortable tenderness.

Eventually, my months spent searching delivered some conclusions. In all likelihood, my obsession, far from something supernatural, stemmed from a simple truth: Mihelič’s work found me at a particularly vulnerable juncture. My parents are aging and isolated; life, for them, is becoming more difficult. My time with them is ever-dwindling. In 2022 and 2023, I had friends die unexpectedly. The end of the Trump-era protest momentum, accelerated by the pandemic, has gutted the political movements to which I devoted my 20s—and, in the U.S., in Slovenia, and around the world, the political horizon appears increasingly foreshortened.

The future holds bleak visions of a world on fire. State repression is escalating at home, and abroad, genocide is being waged in Gaza, aided by American weapons and funded by our tax dollars. Every day we are subjected to an appalling disjuncture: the juxtaposition of middling corporatized media and images of profound human suffering. All while many of us suffer in the quiet way Mihelič did, living spiritually and materially impoverished lives, amidst crumbling empires.

In these conditions, Mihelič’s work is exceptionally resonant. And yet, while tempting, it would be a mistake to read his work—though it is indeed yearning and full of pain—as nothing but a bleak testament. Mihelič is not bleak in the way of Francis Bacon, or his Slovene contemporary Marij Pregelj. His is the type of bleakness that John Berger characterized as “the acceptance that the worst has already happened.” A man who fears, as Mihelič feared war and death and human peril throughout his life, is incompatible with true nihilism.

While his art is elusive, ideologically and stylistically flexible, Mihelič—even when he turned inward to seek the universal among the particular—never abandoned the world for his own interiority. He was conscious of the fact that they are linked—and his explorations of that terrain offer us the chance to see ourselves in the same stripped-down condition of mortality, to look at that which we are most afraid of: the end.

Though he would take a long route through differing depictive methods, his style never became fully abstracted, never fully surreal, never fully expressionist. That level of remove would have represented a retreat, and he did not retreat from trying to reconcile mortal fear and human suffering with the indifference of matter. In the end, it was because of his refusal to shy away from the reality of death that the merits of his art, throughout all its eras, were so indelible: his work always remained grounded in the real. When others looked at Heaven, the abstract, the ideals of man, Mihelič looked at the dirt.

What Soklič said was true, yes: France Mihelič’s art is about the shared experiences of death, grief, and disappointment. But what sets him apart in my mind is that he always worked in that moment bridging death and transformation, the moment before the after. Decay, his paintings contend, is also a form of life. He stands as an observer of the assiduous pageant of existence. Matter can neither be created nor destroyed—merely transformed. There is always the earth and the soil, the continuity of respiration, the potential beyond the end, that last fragment of consciousness and the unknown. And then, somewhere beyond the shadows, life again. ♦

The author would like to thank Boštjan Soklič and

the Mihelič Gallery at the Škofja Loka Museum.

Inquiring minds can view the work of France

Mihelič at the Mihelič Gallery in Ptuj, the Narodni

Galerija and Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana, and

the Mihelič Gallery in Škofja Loka.

Cover image: Leteče maske, 1974, acrylic on canvas.