This article was authored in June 2024. It appears in our fifth print issue, Contra Temps, available here.

♦♦♦

“If the Jew did not exist, the anti-Semite would invent him.”

JEAN-PAUL SARTRE (1946)

“If the State of Israel didn’t exist, imperialism would invent it.”

ABDELKEBIR KHATIBI (1974)

“Were there no Israel, America would have to invent one.”

JOE BIDEN (2015)

♦

The modern history of Zionism as a settler-colonial ethno-nationalist ideology and practice is also the history of the ruptures it has recurrently elicited within the Jewish diaspora, as well as among social movements and intellectuals worldwide. Though emerging at a moment of quantitatively and qualitatively unprecedented violence wrought by the Israeli state against the Palestinian people, calls for the abolition of Zionism, or for an exodus from it, are not in themselves new. Whether we consider the Balfour Declaration, the Nakba and the foundation of the state of Israel, the wars of 1967 and 1973, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, or the two Intifadas, the political crises in which Zionism has been a leading protagonist have doubled as intellectual crises on the scale of the world.

As we learn from the writings of Robin D.G. Kelley, Michael R. Fischbach, Greg Thomas, and others, the momentous fault line between “civil rights” and “Black power” in Afro-America’s liberation movements was also drawn and redrawn with reference to positions taken around Palestinian solidarity and the racial-colonial dimensions of the Zionist project. Similarly, when the June War broke out in 1967, shortly after a singular philosophical-diplomatic tour that had taken the French philosopher to both Gaza and Tel Aviv, Jean-Paul Sartre’s equivocations around Zionism and Palestinian liberation led to the nigh-on total collapse of his standing as a thinker of anti- and post-colonial freedom in the Arab world. Frantz Fanon’s widow Josie instructed the publisher François Maspero to remove Sartre’s preface from all future editions of The Wretched of the Earth. Sartre’s partial apologias for Israel would also occasion a coruscating polemical tract by the Moroccan literary critic, novelist, and poet Abdelkebir Khatibi, Vomito Blanco: Zionism and the Unhappy Consciousness (1974), which I’ll turn to by way of conclusion.

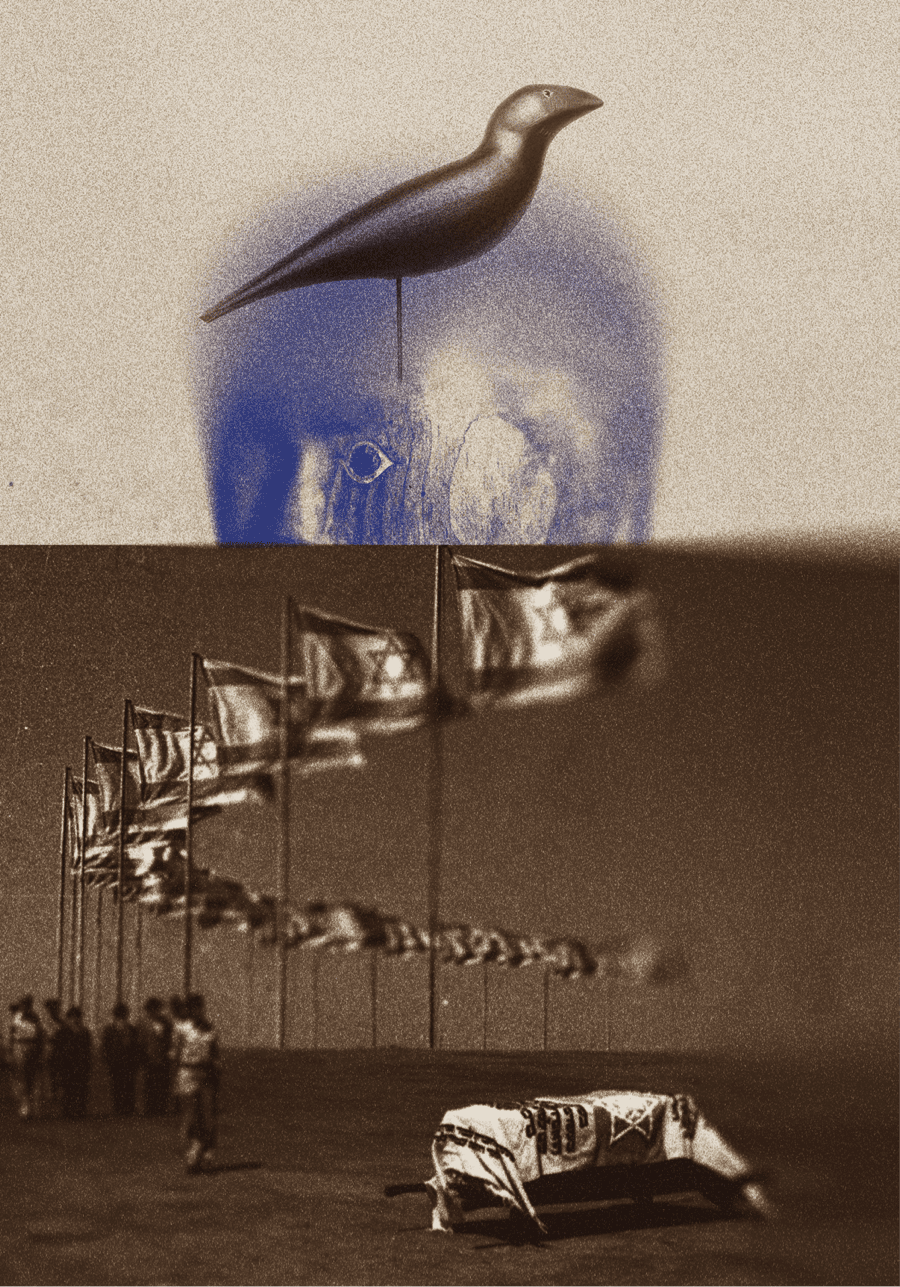

Some of the most eloquent reflections on this ethical and political labor of division were advanced by the poet and critic Franco Fortini, a communist “non-Jewish Jew” (to borrow Isaac Deutscher’s formula). Fortini penned a remarkable memoir-pamphlet, The Dogs of the Sinai, on what he regarded as the abject and unthinking rallying to Israel of much left and Jewish opinion in Italy on the occasion of the “Six-Day War.” (He also had some acerbic words for the Italian Communist Party’s tailing of the Soviet line and its rhetorical Nasserism.) In Dogs (which was rendered into a powerful essay-film by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet called Fortini/Cani), Fortini tells, in a poetic and unsparing auto-analysis, of the pressure and entreaties from Jewish family members or political acquaintances to declare himself for a supposedly besieged Israel, and of the recalibrations of his own experiences of both anti-fascism and antisemitism which the war and its ideological repercussions elicited.

This is also a story of class, of the writer’s own place in the history of the (Jewish, intellectual, leftist) petite bourgeoisie. As he observes: “If I have changed, I owe it to this—to the way in which great world events forced me to interpret myself differently.” In this view, the political break is always also inner, as is a class struggle that counsels against excessive sensitivity to personal slander: “In what concerns political choices and judgments, for those who adopt class conflict on a global scale as their standard, it is ridiculous to say ‘I do not tolerate’ or ‘I do not allow.’ If you know that class conflict is the last of the visible conflicts because it is the first in importance, that it is outside of any natural ‘right,’ one of the ‘base things of the world,’ of the ‘despised’ things, the ‘things which are not’ [Corinthians 1:28], you must, in a sense, ‘tolerate’ and ‘allow’ false accusations.”

This sensitivity to the shaping force of class struggle—in its geopolitical manifestation as imperialism—also animates Fortini’s intransigent and Brechtian apologia for the virtues of political simplicity, so resonant today when liberal editorialists and litterateurs once again sing the virtues of nuance: ”For the sake of those who love to remind you that the world is complex, that simplifications stem from intellectual uncertainty or stereotyping, from an unresolved Oedipus complex or—it would amount to the same—from the authoritarian personality, I will note that the complexity of the real, its interpretation on an infinity of levels, does not exempt anyone from an objective simplification, from the inscription of every life in an order of behaviors that are class behaviors… subjective simplification [is] a provocation, a reagent that induces the others to register their class identity, their inner clinamen. As long as the June war had not been fought and won, distant observers could remain uncertain about the degree of class commitment, of fidelity to imperialist service, of the Israeli political leadership.”

This play of objective and subjective simplification is a crucial dialectical lesson in Fortini, which remains shadowed throughout by its own ethical moment—in which the affiliation that stems from solidarity with the oppressed requires the symbolic violence of a disaffiliation from those who claim you as their own. When Fortini returned to the question of Zionism in the wake of the first Intifada (in his last collection of essays Extrema ratio: Notes on a Good Use of Ruins, and in a “Letter to the Italian Jews,” published in il manifesto in May 1989 and signed with his Jewish last name, Franco Lattes Fortini), a bleaker political horizon intensified the ethical moment, which carried its own echoes of Biblical oratory.

As he declared: “There are causes (of justice and solidarity, of international anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist war; let everyone choose among these the one best suited to them) for which it may prove necessary to break the toughest and dearest bonds; that is, to choose what to put first, loyalty to a country, an ethnicity, a culture, a religious or familial tradition, to one’s own dead or instead to something other. I who write have put this ‘other’ first, every time I was faced with a conflict between duties and loyalty.”

In a provocative reference to the plagues visited by Yahweh upon Egypt in Exodus, Fortini asked his fellow Italian Jews to “bear a sign,” against loyalty and for solidarity with the Palestinian other. He declaimed: “Let them have the courage to wet the threshold of their doors with the blood of Palestinians, hoping that in the night the angel won’t recognize it; or let them instead find the strength to refuse complicity with those who stain the earth with that blood every day, and who scream against that angel. And let them not lie to themselves, as they do, equating terrorist massacres with those of a disciplined and organized army. Their children will know and they will judge. And if I were to be asked with what right and in the name of what mandate I dare to utter these words, I will not answer that I do so to bear witness to my existence or to the last name of my father and his descending from Jews. Because I think that the meaning and value of human beings lies in what they make of themselves on the basis of their genetic and historical code and not in the destiny that they received with it. On this point above all—refusing every ‘voice of the blood’ and every value to the past where spirit and the present haven’t first laid their claim; so that the former are judged by the latter—I feel distant from a crucial tenet of Judaism or what seems to be its current manifestation.”

In 1968, another Italian “non-Jewish Jew,” also a heterodox communist in his own right, the Germanist and mythologist Furio Jesi, made a public break with the rallying to Israel and Zionism of his comrades and contemporaries. In Jesi’s case, the break was also an occasion to apply a crucial concept from his analysis of the multiple entanglements of myth with nationalist, fascist, and revolutionary-conservative right-wing culture. That concept was “technicized myth.”

Originating in the work of the Hungarian mythologist Károly Kerényi (who juxtaposed it with “genuine myth”), anticipated in a political vein by Georges Sorel’s Reflections on Violence, and given literary expression in Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, the idea of technicized myth as a crucial mechanism of contemporary ideological production was directly applied by Jesi to Zionism, leading to anathemas even more lapidary than those experienced by Fortini. A myth is technicized, according to Jesi, when it comes to be instrumentalized for political ends, namely the accumulation of power by a social group or a governing class. For Jesi, this weaponization of myth’s supposedly transhistorical and transcendent truth, this marshaling of its symbolic force for profane ends, was always reactionary, even when it was enlisted by progressive forces.

In the wake of the Israeli-Arab war of 1967, several Italian Jewish intellectuals associated with the liberal-socialist resistance against fascism and Nazism (including Primo Levi) had written multiple pleas for solidarity with Israel at a moment of crisis in the pages of the journal Resistenza: Giustizia e Libertà. (The subtitle directly references the main resistance formation of the non-Communist Party left.) The younger Jesi intervened as a dissenting voice in Resistenza, drawing on Martin Buber, Ahad Ha’am, and traditions of “cultural” and “spiritual” Zionism (of the kind more recently explored by the Israeli scholars Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin and Shlomo Sand) to denounce Israel’s propagandistic uses of theology to bolster a colonial project integrated into the broader designs of U.S. imperialism—a project which was, for Jesi, openly enacting what the Haggadah condemned as “the three sacrileges that can deprive the Jewish people of the rights to the land of Zion: the shedding of blood, idolatry, pride.”

Buber had written that for “political Zionism,” “the State is the goal and Zion a ‘myth’ that inflames the masses.” That propaganda employed to shore up nationalist militarism and settler-colonialism could leverage European guilt to “distort and exploit respectable religious beliefs to justify Israeli politics” undoubtedly placed political Zionism in a broader family of 20th-century politics grounded in the technicization of myth, of which fascism was the crucial example. Zionism’s instrumentalizations of theological texts belong to the ambit of what Jesi termed “right-wing culture,” understood as one “made up of authority, mythological security about the norms of knowing, teaching, commanding, and obeying,” in which “the past becomes a kind of processed mush that can be modeled and readied in the most useful way possible.”

Yet we could also argue that this “technicization” of the Bible as myth to legitimize, sacralize, and guide settler-colonial dispossession and war for transfer, ethnic cleansing, and genocide, while a leitmotif of Israeli state and settler ideology, is itself mutable. As Rachel Havrelock details in her compelling study The Joshua Generation: Israeli Occupation and the Bible, for David Ben-Gurion, “No one had better interpreted Joshua [the conqueror of Canaan] than the Israeli Defense Forces in 1948 [and he saw] the enactment of Biblical archetypes as the most fitting form of Biblical commentary.”

But we can note significant developments between, on the one hand, Ben-Gurion’s convening of a governmental study group on the Book of Joshua in the early 1950s to ground a basically secular if religiously legitimated project of colonial state-building and dispossession (“God doesn’t exist but he promised us the land”), and, on the other, the volatile synthesis of settler violence, authoritarian capitalist statism, and fundamentalism that has led the Israeli government and state on a seemingly irreversible path of fascization.

In 1980, the student paper of Bar-Ilan University published a piece by Rabbi Israel Hass on “The Mitzvah of Genocide in the Torah,” in which he drew on Deuteronomy’s commandment to “obliterate the memory of Amalek” to justify the coming need for a war of annihilation against Palestinians, which would not spare even the children. At the time, he was dismissed by the university. Now, Israeli government ministers voice similar views, using identical language regarding “Amalek,” on a quotidian basis. For the likes of Bezalel Smotrich, repeating the Nakba is a duty, a vocation, and its blueprint can be drawn from the Bible. (Again, the Book of Joshua proves to be a salient source for the theological justification of dispossession and annihilation, though as Havrelock has compellingly argued, it also harbors imaginaries of cohabitation.)

This is what Smotrich declared: “When Joshua ben Nun [the Biblical prophet] entered the land, he sent three messages to its inhabitants: those who want to accept [our rule] will accept; those who want to leave, will leave; those who want to fight, will fight. The basis of his strategy was: We are here, we have come, this is ours. Now too, three doors will be open, there is no fourth door. Those who want to leave—and there will be those who leave—I will help them. When they have no hope and no vision, they will go. As they did in 1948. […] Those who do not go will either accept the rule of the Jewish state, in which case they can remain, and as for those who do not, we will fight them and defeat them. […] Either I will shoot him or I will jail him or I will expel him.” Is there a clearer example of “technicized myth,” and of the instrumentalization of Biblical text to shore up a racial-colonial order grounded in a logic and a practice of elimination?

But Zionism’s Biblical technicization of myth has been soldered to a possessive politicization of the Holocaust as Staatsräson—not just of Israel but of its Western allies too, for whom defense of the Jewish State trumps putative international law obligations to prevent genocide, consolidating the bankrupt post-truth liberal imperialism on daily display at U.S. State Department pressers. This is also what the likes of Jesi and Fortini were responding to: the former by integrating his own studies of antisemitism and blood libel into a broader philology of the political uses of the concept of “savagery,” the latter by stressing, in an echo of thinkers like Césaire, that the meaning of the Holocaust had to be articulated alongside those of the long history of racial and colonial genocides.

Or, as Fortini put it in The Dogs of the Sinai, the meaning of the Nazi massacres was “to have summed up, in the position of the victims and in an incredible concentration of time and ferocity, all the forms of domination and violence over man characteristic of the modern era; to have reproduced, for the use of a single human generation, that which, distended in time and space, in habit and insensibility, the European subaltern classes and the colonized populations had undergone by way of denial of existence and of history, as alienation, reification, annihilation.”

Today, genocide itself has patently transformed into what culture-war legislators of the right term a “divisive concept,” as many seek to contest the dire effects of Zionism’s efforts to monopolize it, to technicize it for the purposes of ongoing domination, and indeed to provide cover and legitimation for… genocide. After Israel’s invasion of Lebanon and its effort to obliterate the Palestinian liberation movement, Gilles Deleuze—whose own friendship with Michel Foucault had been broken by divergent positions on Israel and Zionism—grasped this process with remarkable and prescient acuity, in his critique of ways in which the category of “absolute evil” was used to shore up Israeli crimes. As he observed after the massacres of Palestinian refugees by Israeli-backed Phalangist forces at Sabra and Shatila:

“It’s said that this is not a genocide. And yet it’s a story that consists of many Oradours [a French village destroyed by the Nazis in retaliation against the Resistance], from the very beginning. Zionist terrorism was practiced not solely against the English, but on the Arab villages which had to disappear; Irgun was very active in this respect (Deir Yassin). From beginning to end, it involved acting as if the Palestinian people not only must not exist, but had never existed at all. The conquerors were those who had themselves suffered the greatest genocide in history. Of this genocide the Zionists have made an absolute evil. But transforming the greatest genocide in history into an absolute evil is a religious and mystical vision, not a historical vision. It doesn’t stop the evil; on the contrary, it spreads the evil, makes it fall once again on other innocents, demands reparation that makes these others suffer part of what the Jews suffered (expulsion, restriction to ghettos, disappearance as a people). With ‘colder’ means than genocide, one ends up with the same result.”

A few years earlier, in the aftermath of the rallying of public opinion to Israel that followed the Black September operation at the Munich Olympics, Khatibi’s Vomito Blanco had tried to unravel the conundrum of that Western bad faith that oversaw and overlooked what he then called the “ethnocide” of Palestinians. Drawing on Jean Wahl’s reading of Hegel and a Nietzschean literature that included Deleuze and Guattari, Khatibi called for a polemical anatomy of that “morality of sin and the unhappy consciousness” that underlay Western Europe and the United States’s Israel apologias and made it possible for “Zionism to feed on what the racist West has been unable to absorb, so that this moral nausea now spills over again onto the Palestinian people.”

Just as it was for Deleuze, to Khatibi, the ruse of Zionism was to play relentlessly on the register of the absolute, “to wave the phantasm of genocide, stubbornly confusing absolute war with limited war.” Zionism was not just a desire to be the Occident within the Orient and to expatriate the Palestinians—it was also a psycho-political and speculative effort to “transfer” its negativity, its internal consciousness of contradiction—the definition of the “unhappy consciousness”—onto the Palestinians, in a violent exteriorization and projection that is reminiscent of the Frankfurt School analysis of the inverted mimetic logic behind antisemitism itself. One is also reminded of Edward Said’s observation in “Nationalism, Human Rights, and Interpretation” (his contribution to the 1992 Oxford Amnesty Lectures), according to which “the liberal tradition in the West was always very eager to deconstruct the Palestinian self in the process of constructing the Zionist-Israeli self.”

What Khatibi polemically suggests is that while a European left willing to generate alibis for Zionism is mired in the unhappy consciousness—witness the collapse of the foundations of Sartre’s philosophy of praxis and ethics of commitment at the time of the 1967 war—Zionism itself functions as a bitterly “ironic reversal of the unhappy consciousness: the end of the exile of the Jewish people demands the exile of the other, the appropriation of the Promised land presupposes the dispossession of the other, the foundation of a state, the destruction of a people, the Nazi genocide is followed by the Palestinian ethnocide.”

Thus, “the war against the exiled other becomes a system of cruelty, covered and mystified by bad faith and an inverted mysticism.” On both the side of Zionism and that of its liberal and leftist apologists in the pages of Les Temps Modernes—two symbiotic modalities of the unhappy consciousness—Khatibi discerns the working of a frighteningly efficient machine of misrecognition, one that requires by way of antidote the reinvention of a Nietzschean critique of the kind of morality of transcendence, guilt, Good, and Evil that underlies Zionism’s transference of negativity. (For Khatibi, Palestinian resistance fighters model a politics beyond ressentiment, a “strategy of excess” against the machinations of culpability.)

As Khatibi puts it, “Zionism wants infinitely to hide the other to escape the exile of the self, to the point of erasing the face and the proper name of Palestinians; it wishes infinitely to transfer guilt onto the other to bring to an end its own unhappiness,” in a radical refusal to countenance or think difference. It is a kind of political mysticism based on the compulsion to vomit out the other, whose very existence and name is not just a material obstacle to sovereign domination, but a challenge to “the mystified totality of the origin,” to “the justification of Zionism by culpability, namely of one absolute by another absolute,” and lastly, to “Israel as a punishment inflicted by the West on Palestinians.”

In recalling the force of Khatibi’s philosophical polemic half a century after its original publication, we should also acknowledge that the unmatched brutality of the present moment casts doubt on the centrality of ideological critique. No doubt Zionism continues to operate overtime as a machinery of culpability and exculpation, but, as commentators like Ilan Pappé and Shir Hever have recently noted, it is also undergoing what looks like a terminal, if very protracted, legitimation crisis: a paroxysm of dominance in the ruins of hegemony. While its “liberal” apologists are rife in the West, and their efforts to sabotage and punish Palestine solidarity relentless and multifarious, its principal form in Israel now is that of unalloyed racist affirmations of supremacy and genocidal domination, whether as fascistic settler messianism or craven and corrupt authoritarian capitalism.

Where critiques like Khatibi’s cut deep into the ideological formations of “liberal” Zionism and its Western apologists, I am not so certain that the raw affirmation of Jewish supremacy over historic Palestine (and beyond) is still haunted today by duality, negativity, or contradiction—that it rises to Hegelian categories—though it may be meeting its limits in the internal decomposition and crisis of Israeli society, and enduring resistance in Palestine and across the world.

From Jewish communist intellectuals to Arab cultural life, from Black liberation to French radical philosophy, our political orientations and vocabularies already bear many sedimented traces of the imperative to heed the language of Palestinian liberation, to break with Zionism’s colonial logic of domination and elimination, and to work towards freedom and equality from the river to the sea. Today’s fight against Joshua’s ultimatum, within and beyond Palestine, is also a process of reactivating some of these traces, of finding new lines along which to divide our concepts, our practices and our solidarities, all the better to struggle for a common humanity. ♦