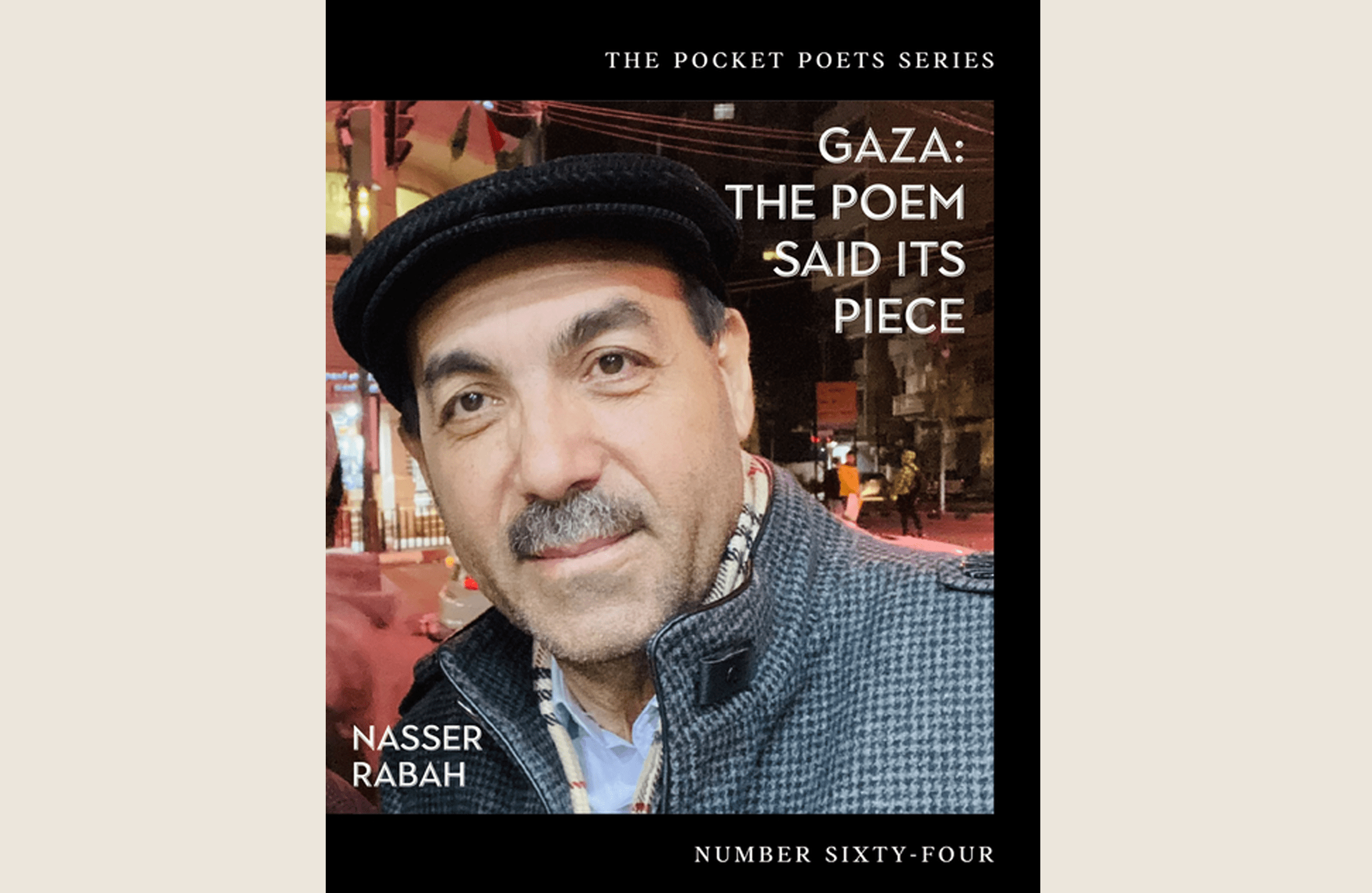

One poem by the Gazan writer Nasser Rabah features a cake shaped like a heart; the speaker purchases it for his own birthday, and splits it among “the kids”. But “the piece no one wanted,” he goes on, “I kept for the poem.” We might think of the oracular, elliptical bent of Rabah’s extraordinary poetry—selected and translated by Ammiel Alcalay, Emna Zghal, and Khaled Al Hilli in the collection Gaza: The Poem Said its Piece—as composed of just such unwanted odds and ends, emerging from dust-heaps in recuperated glimmers. But that “piece,” in a serendipitous pun that the translators have cleverly drawn on for the book’s title (and that doesn’t exist in the Arabic), is also what the poem ends up voicing in its brokenness.

Absence in this volume approximates the form of a suitcase, a tune, a door, a stench, dislocated from one sensory apparatus to another; tears fail to flow because, like the body that emits them, they’ve “lost their watch and shadow / during the war.” What seems like a surrealist, oneiric logic of unexpected juxtaposition might simply be a gesture toward a horizon of time so out of joint, and so brutalized by the Israeli genocide, that only shards remain. And layer them over one another is what Rabah does, enfolding affects, objects, scenes, losses together with such kaleidoscopic velocity that it feels like he’s assembling a mysticism of his own.

“If I were to pick only one poet from Gaza to be translated and published in the English-speaking world,” Mosab Abu Toha wrote in his introduction to the collection, “this is who it would be.”

At one interval, near the end of our extended conversation on Whatsapp, Rabah apologized and told me he would respond soon. He wasn’t in a position to at that moment, as there was “real war” and “real hunger.” That day, Israel had just massacred Palestinians who, subject to an enforced famine, had been seeking food at an aid distribution point.

I didn’t know what to say; there was nothing to say except to pray that God would keep him and all the other Palestinians safe. When we in the imperialist core hear about these atrocities abroad—and even a word like “atrocities” no longer cuts it, no longer matches up to the apocalyptic scale of the genocide—and then the silencing and punishment inflicted, here, on those who dare to name that injustice; when we take in all that, how can we continue to have faith in this rotten world, straining at the seams of its stitched-together fictions?

That I could speak to Rabah at all felt, and continues to feel, like a miracle. I was apprehensive at the outset about potentially perpetuating the trap of tokenism that the Anglophone world so condescendingly slips into, turning a Palestinian poet into a spokesperson for his own people. Neither did I want to resort to questions about “the role of literature in genocide”; these ultimately seem tired to me, poorly matched to the unaccountable force that poetry might continue to hold for some—in spite of, and because of, its impotence and uselessness, its existence beyond what can be instrumentalized.

I hoped, rather, to ask Rabah about how he sculpts language, relates to God, experiences time, addresses himself to Gaza; what kinds of poets he liked to read; why he can’t stand the sight of Mahmoud Darwish’s Complete Works on his shelf. We conducted this dialogue in Arabic, and I translated it into English, editing it for clarity and flow. The translations of Rabah’s poetry are taken from Alcalay, Al Hilli and Zghal’s renderings, except for moments when Rabah quotes from poems that aren’t included in the English-language collection. Many thanks to Khaled Al Hilli for putting me in touch with Rabah in the first place and for the boundless generosity and supportiveness of his mentorship. To borrow from Huda Fakhreddine: may we continue to hear Gaza in all the poems we read, and in all the lives we continue to live.

[Ed. note: These interviews have been lightly edited for length and clarity.]

♦♦♦

Alex Tan: It’s impossible to begin without referring to the genocide that Israel is committing in Gaza, and the complicity of the Western world in Israel’s crimes. The sheer scale and brutality of the destruction escapes language. Yet you and so many others continue to write. In your poetry, I feel as if speech is always on the verge of extinction.

“Die a little, O Speech,” you write in “Prophet of the Lost Way.” In “Distorted Dreams,” you instruct the poem’s “you” to “Say something […] before your mute words end in heartbreak.” How do you experience the “ache of writing” and its silence in relation to the act of speech? From what place within you, or outside you, does the poem speak?

Nasser Rabah: The act of writing, for the writer, is a chronic affliction, an unending yearning, a perpetual torment. It is Sisyphus’s rock. I write to validate my own existence, and to express myself. But writing, at the same time, is a kind of birth. My wife once told me that she notices how, while in the thick of writing, I enter into a nervous psychological state akin to the pain of labor.

In a time of war, what I write is not poetry—rather, I merely describe what I see and feel without need for significant literary intervention. What has taken place so far defies the imagination and surpasses metaphor; it is, in and of itself, poetry that aches. In a time of war, then, I write in order to preserve my sanity. Writing represents an act of resistance: it militates against all that is base and hateful, against death and annihilation. If writing is life, and life itself has turned into war, what more is left for us to write?

AT: I feel moved by what you say about writing as a form of birth, a way of giving life to another. Paul Celan writes, in “The Meridian,” that “the poem is lonely. The poem intends another, needs this other, needs an opposite. It goes towards it, bespeaks it. For the poem, everything and everybody is a figure of this other toward which it is heading.”

Who is this other in your poetry? In “The Garden of Madness,” you write about how “the path on which you cross toward me” is “muddled” by “soldiers, and the dead, and the bearers of false flags.” What kind of addressee do you imagine, when you write? If war and ideology are obstacles, how do you hope for your reader to cross towards you?

NR: Each poem’s first addressee is always myself. The addressee that comes after depends on the text. Sometimes I speak to God, my mother, my homeland, even language itself. The path towards me is often hazy and muddled, but that’s the reason I write, in the hope that a reader might—by hook or by crook—arrive at what I mean.

It’s not up to the poet to capture everything with a camera’s eye. Instead he should attempt, in the simplest of words, to evoke mystery, bewilderment, and doubt—a task that challenges and delights in equal measure. I’d rather my readers attend to the aesthetics of my language and imagination than obsess over meaning and intention.

I once wrote, “The slogan stays fixed while life changes shape.” I dread being judged for my writing as if it were nothing more than a slogan. Everything I write is tethered to the moment in which it comes into being and is always susceptible to change.

AT: I’m looking at the poems in which you address God. I sense yearning and quiet in them, as if you have crossed a threshold. In “Stewing My Groans,” it seems that the speaker abandons familial ties to become “an orphan with no beginning” or “end.” There is also a moment in “Meditations” when the speaker says to God: “and all I’m waiting for is a sign.”

I wonder if this loneliness and this ambiguity is similar to what you describe, when you talk about poetry—this aspiration towards truth, “ascending the staircase of the soul without face or mask” (from the poem “Ascension”). You say that “the bullet of God is a word”; maybe language itself is sacred. What relationship to God do you aspire to form through your writing? Is there an element of prayer in the quality of attention that poetry lends to the things around us?

NR: Poets often fall back on denying God or gesturing toward him with flippancy and pomposity—perhaps because they fancy themselves mini-demiurges and plume themselves on their ability to compose poetry.

I find this absurd. To the contrary, I have total conviction that God’s existence represents the final bulwark at a moment when all other walls—national, political, human—are collapsing around us. Throughout this ongoing war on Gaza, I’ve felt more keenly my own longing for God, but also His presence dwelling within me. Only with this faith have I been capable of living steadfastly through this ordeal.

Having come of age in the East—an environment that favors tolerant religiosity—I imbibed the culture of the soil in which Christ walked and preached. When I write, I try my best to draw attention to this connection and this distance from God that accordions—now expanding, now contracting. Between us is a relation of intimacy.

In my writings, I depict myself as a man ever in search of that frisson. One that touches him and purifies his soul into a transparency that discerns what others cannot. Poetry is both love and contentment—the gift that God bestows in the hearts of those who seek Him. But poetry, at the same time, can be the condition of strain and disquiet that ensues when life snatches that clarity away from us. My poem “Stewing My Groans” embodies the sense of loneliness and isolation that comes of trying to reach God; in lamenting to him, I stew my groans.

AT: Your response makes me think of how faith holds us aloft in the face of death and time. Sometimes, your poetry gives us a window onto the absence that the war leaves behind, which outsiders cannot possibly imagine. In your poem “Early Absence,” you repeat the phrase “not enough time” like a refrain. The horizon of time narrows; there is not enough time for living, for dreaming and singing. But you also ask the question, in the aftermath of devastation, “to whom should we recite the Fatiha?” And then, “to whom should we recite the time?” If the recitation of the Fatiha measures the passing of time, can time be an opening towards God?

I’m asking myself, now, if this changes the way we think about history. Huda Fakhreddine wrote, “If, as Bashshar ibn Burd says, the true test of poetry is time’s inability to extinguish it, that it persist in its presence regardless of time’s passage and remain ever capable of expressing the reality of the language and its people in the present’s fugitive instant—beyond the reach of history and its trajectories of injustice—then we must hear Gaza in every Arabic poem.” What does history feel like to you in a time of war and catastrophe? How does time move in a poem, and through a poem?

NR: The measure of time is relative in life, and even more fluid in text. Texts pay no heed to measurable time; they often incarnate a nostalgia in which the past extends into, and bears upon, the present. Or they narrate the present as it stretches forward to anticipate the future, like a visionary premonition.

Some texts, laudatory in nature, extol the virtues of maxims and slogans, but they delude themselves into a false sense of permanence and fixity—an illusion exposed by the constant mutability of life. A poem that endures through the ages is one with elegance of language, imagery, and structure, even as the intellectual charge it carries, however potent, must remain open to contestation.

In Gaza—and in war—“time kills itself,” as I wrote in the poem “In the Endless War”: “time is better measured by martyrs.” Mahmoud Darwish has that famous phrase, “no time for time.” And time has stolen away from me, many in Gaza have likely repeated to themselves. Time here seems to plunge into a void; a year or two might pass without us noticing that it’s slipped out of our lives.

I strongly believe, too, that the years of war are akin to black holes punctured in time, swallowing up the remnants of our existence. Even after the war, we’ll remain hostage to that thwarted clock—never will we be rid of its psychological and moral imprint. I’m not surprised that images of waiting and of broken clocks recur in my writings on the war. In my poem “Military Evacuation Orders,” for example: “The long fingers of war are like a broken clock.”

The poet who abhors war stands against its spectacle of madness, the suffering it produces; against the pain, death, and agony of other human beings. This posture leads him to reject time in its totality—a state of temporal denial, as if sinking into a perfect hibernation that will last until the war ends.

Above all, poetry and literature in Gaza—and maybe the Arab world at large—won’t be able to easily liberate itself from this moment: like a wounded gazelle, fettered by the chains of war.

AT: I feel I have to ask about Mahmoud Darwish, since you mentioned him. One of your funniest and most biting poems is “The Trace of Your Butterfly”; I remember Ammiel Alcalay reading it out at a tribute event for Darwish. Everyone laughed at the opening line: “It’s been a while since I’ve wanted to figure out why I can’t stand Darwish’s Complete Works in my library.” The descriptions of Darwish’s “withering smirk” and “unreasonably straight hair” were incredibly amusing as well.

Given Darwish’s status as a titan in the Palestinian and Arabic literary canon, how do you deal with him and his butterfly? Do the traces of any other writer weigh upon you, when you write? More broadly, how do you work within or against the Arabic poetic tradition?

NR: Mahmoud Darwish is my eternal muse and inspiration. I’ve always loved him deeply. The poem you referred to was my way of paying oblique tribute to him. He was the beautiful face of Palestinian culture, who made me proud to be a compatriot, and a paragon in every sense. From the astonishing elegance of his language and the encyclopedic depths of his cultural knowledge to his captivating diction and prolific output, he had a style that evolved with each new poem he put forth. He was also eye-catchingly handsome.

At the outset of my poetic journey, I lived in Cairo, and because I’m Palestinian, friends would compare me to Darwish. I felt it was unfair; I knew I’d have to avoid Darwish’s influence as much as I could, if I wanted to distinguish myself as a poet. He’s one of the most dangerous poets in the world when it comes to the sheer sway he exerts over the minds of his readers, especially those who try their hand at poetry; the trace of his butterfly will never fade.

My strategy was to consciously write in a different way, ridding myself of all Darwishian vocabulary, turning against the elevated rhythms of his verse. Most of all, I avoided reading his poems—they have a way of worming into your subconscious and giving voice to the private music of emotion. Out of this anxiety of influence, I turned to novels instead. They furnished me with a more expansive source, nourishing my lexicon, my imagination, my repertoire of images.

I tried my best, too, to read as much as I could of Palestinian poets whose styles diverged from Darwish’s, like Zakaria Mohammed and Ghassan Zaqtan. From the Arab world, I took inspiration from Amal Dunqul and Saadi Youssef; from the West, Yannis Ritsos and Nazim Hikmet were models. But I read them less to immerse myself in the aesthetics of their language, their rhythm, their imagery; I was more interested in unpacking the poems and understanding how the sausage gets made. I paid attention to craft—the elements which rendered each voice unique.

The Arabic poetic heritage is rich, bounteous, endless. I consider myself an heir to the vast reaches of its language—and I strive to carve a place for myself and my poetry within it, caught somewhere in between the far-reaching, authentic lexicon of Arabic and the fluidities imposed by modernity.

AT: Do you also take inspiration from Wadih Saadeh? I noticed that in your poetry, many transformations and metamorphoses happen, sometimes leaving behind evidence of life and memory. Objects have many lives; a vase could be a heart, and a street might be paved “so the memory of your dead friends doesn’t trip.” To my mind, it resembles moments when Saadeh tells himself to “throw nothing away,” because “The thing you throw may be a friend who wants to stay.” How do you come into contact with the spirit of an object or body that has become something else or taken on another physical form?

NR: Wadih Saadeh is one of the greats. When asked if he ever worried that inspiration might run out and that he might go for a while without writing, he replied, Would anything in the world so much as bat an eyelid if Wadih Saadeh ceased to write?

His answer taught me a great deal. A kind of reconciliation with oneself that elevates the spirit and renders one almost monastic—as if seated atop the Himalayas, beholding the world beneath one’s feet. Such a posture of surrender and asceticism opens up, within the mind, windows to visionary depths; one sees through the lens not of knowledge and experience but of the heart and its wisdom. With that peace one acquires the capacity to meditate, to discern the speech of stones, to hear the lamentation of trees, to give ear to the laughter of the dead.

The title of Saadeh’s collection “Evening Has No Brothers” intersects with my own outlook on life: I treat everything as if it has a soul; parley often with my deceased mother and father when I write about them; keep stones from Jericho because they specifically call Zakaria Mohammed to my mind. I love rivers for the way they whisper to me, and eschew coasts for their din and the prattle of waves. A black shirt, to me, can be a real friend; a door that creaks might have a coarseness in its bones; birds are missives.

Once, I stood before the grave of Paul Valéry in southern France, humbly entreating him to grant me his talent. From then on, I began to write differently. During the war I wrote: I’ll bid farewell to my library for a safer place, leaving it to face a horizon of tanks. A week later, the house was bombed. Only the library was hit, and by two tank shells at that. My life unfolds like a street with two sides: one is characterized by brute realism and dry logic, the other by something more spiritual and dreamlike. I walk along one edge, peering at the other.

AT: Why Paul Valéry? What changed in your writing after you stood in front of his grave?

I know he has a poem, “Graveyard by the Sea,” and I just found an Arabic translation. He writes, “I breathe the smoke I will become […] I surrender to this shining air, / My shadow sweeps the houses of the dead / And with its fragile motion leads me on.” [Ed. note: This particular quote in English is from Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody’s translation.] Does Valéry come to mind when you commune with the dead and the absent?

NR: When we first encounter poets in person that we’ve read or heard about, we shake their hands with warmth and smile at them with affection. Even if we lack a personal acquaintance, intellectual affinity suffices. The same happened with Valéry: I happened to be in the city of Sète. Visiting the graveyard by the sea, I found myself standing before the grave of a great poet. That same affinity existed between us, as if I were meeting a living poet. The only difference was that I imagined he no longer needed his poetic talent.

The texts I wrote after that emerged with greater ease and flow—with more complex, sometimes even obscure, images and linguistic structures, as if addressing themselves to entangled worlds. For instance, in “The Flattery of Air”: “Don’t listen to air flattering your clothes, take it as old sighs the place repeats for people who pass through quickly…” Or in “Distorted Dreams”: “How long have you been throwing fish in the river, to make the river believe itself and stop climbing balconies?”

At any rate, it was a phase in my writing life, which itself has changed significantly since the beginning of the bloody events in Gaza.

AT: Can you say more about how your writing has shifted since the genocide in Gaza began, and how it has passed from one phase to another?

NR: Recent events have greatly altered poetic expression. No longer does the poem concern itself with imagery, imagination, and metaphor; it suffices to write what we see and feel, using words that approach immediacy and simplicity, and steering clear of density and complexity. What’s happening in reality speaks with more eloquence than any poetic imagination can. Even if a poet were to exhaust his imaginative resources, he would not arrive at the truth of what’s happening here.

In one poem I wrote, “We train our eyes to miscount our missing limbs.” Many now grow up with severed limbs, and we must train our eyes to witness them as if they were still intact. This is a reality far worse than any poetic imagination can summon.

AT: I wanted to return to Gaza. The final poem in your collection ends, “O Gaza, accursed, beloved, deranged, oppressed, outcast, enchanted, forgotten, mentioned a thousand times in the Book of War, you’re not the Goddess of the Dead, nor is your book called Sorrow of the Country.”

If this is a list of everything that Gaza is not, then what is Gaza for you? Where is Gaza in your heart, and in the world?

NR: The dedication in my second collection reads, “To Gaza, whom no one loves.”

Gaza is a place whose wondrous population brings together all sorts of contradictions; one could call it a cosmopolitan city in a renewed sense. It’s inhabited by those who own the land—farmers of wheat and barley in the north, businesspeople in Gaza City and Khan Yunis, Bedouins in the center and in the south. After the Nakba in 1948, among those who migrated to Gaza were fruit farmers from central Palestine, new professionals from Majdal, residents of cities like Jaffa who were also owners of restaurants and confectionery stores. Each group has a unique accent and distinct character—a diversity that’s turned the place into one brimming with creativity, drive, and culture. I believe the best writers, builders, teachers, and doctors are all from Gaza.

But due to its population density, Gaza is also overcrowded, poor, and ridden with constant cacophony. Added to that are Gaza’s blockaded geographical location and complex political situation, which have fashioned its inhabitants into politicians and freedom fighters; virtually no one can remain politically unaffiliated. Hardly a year passes by without us being tested by war, wrung dry by the blockade, disfigured psychically by the impossibility of moving and traveling freely. We live together in a sardine can, barely able to work or breathe. Yet we still achieve and create.

All of us here treasure the social and intellectual mosaic deeply. But at the same time, we long for a day when we can live without fear for the future. Freedom and mobility are constantly on our minds. The beautiful and the bad: that’s what Gaza is to me.

AT: What dreams do you have for the future? Valéry says, “Time glitters, and dreams are knowledge.” How do you imagine yourself and your poetry moving forward in time?

NR: The dream is the cane I lean on, so that my path might continue to unfurl. And the dream becomes reality if I believe in it; it is a verbal blueprint for the architecture of future days. I dream of a free Palestine, of a state and a flag; I dream that my poem will be sung by generations to come. ♦