Concern over the problem of heterosexual sex pervades social media. Relationship coaches like Sarah Hensley and Sadia Khan have reported hearing from an inordinate number of women that they do not want to have sex with their partners—that they regularly either take steps to avoid it, or perform desire to endure it. The coaches’ advice? Women and men naturally want different things, and to accept this fact is to begin the reparative work required for sexual harmony in a couple.

The story is familiar. Men want to feel masculine and appreciated; women want to feel reassured and loved. Men use sex to relax; women can’t have sex until they are relaxed already. Men want to feel desired and will go elsewhere if they don’t; women want to feel supported and cared for and will put up walls if they aren’t. There are any number of ways to account for the difficulty of maintaining an intimate partnership within the harrying and agitating conditions of contemporary households and work lives.

Yet little of this registers in the world of advice-giving directed at women who want to fix problems in their straight relationships. Instead, women are told to treat their partners differently—to behave and to present themselves in a more feminine way, which is to say, to be less controlling and more supportive, less self-oriented and more partner-directed.

Across this content, which the scholar Jane Ward refers to as part of the enormous “marriage repair industry,” straight women are regularly told some version of the following: Your problems do not arise from how your home and social world are organized. Instead, they are the result of your departure from traditional gender roles. You can repair your relationship and rekindle desire if you manage to overcome a lifetime of messaging from feminists—perhaps including your own mother—and tap into your “inner feminine.” This will in turn enable your partner’s “masculine” to emerge, allowing him to take charge.

Leadership rehabilitates the formerly emasculated husband, and submission allows the reformed feminist to find her place within the couple form and family unit. Modern women have been clouded with conditioning that has made them incapable of allowing themselves to need and love men. This has led to a crisis of gender difference, which poses an existential threat to the abandoned man and the respectable family. The answer is to reinstate gender norms and recommit to family life. Pushing against nature, say these coaches, is a primary stressor—one of the central reasons that our worlds are increasingly deluged by anxiety.

To women’s widespread disaffection and ambivalence, pathologized and diagnosed across online counseling and pseudo-psychology content, tradwife ideology offers its own particular response. “Culture demonizes men for the one thing that bonds a husband and wife together,” as one self-described “traditional marriage” advocate declared on TikTok. In tradwife content, “submission” implies that women must be sexually available to their husbands at all times to ensure that he maintains his natural position as the family’s leader: providing is one part of the husband’s leadership, but it requires its own provisioning in turn. This arrangement restores balance to the family that would otherwise be lost to the corruptive and corrosive forces of feminism.

Feminism’s false promise of freedom, power, and independence has seen women divest from the household, turn away from men, outsource maternity, and seek sex outside marriage. The result is damaged women, maladjusted children, neglected men, and families in jeopardy. Restoration of the family requires not just the repudiation of feminism but the disciplining of wayward desire. A woman’s natural desire is of and for the traditional family—its exclusive preserve and motive, in which sex is properly contained as a path to conception and an act of service. The promise of release from the problem of desire relies on this displacing gesture, in which sex is something you give to someone else, and on the absorption of sex into the naturalized homestead economy, where it is ultimately practiced as an extension of the division of labor.

Tradwife content conforms to a narrow set of narrative devices and discursive styles. One genre of post compares the past self to the enlightened present: the tradwife disavows her former feminist identity and gives thanks for her new embrace of femininity. “Former: feminist/[white flag and rainbow emojis]/pagan saved by the blood of Christ!” trumpets one born-again tradwife. “From Orgies to Christ,” these relationship coaches promise. Feminism and femininity are invariably opposed— you can only choose one.

Tradwives frame their journey as an unlearning of the feminism that ostensibly pervades contemporary culture, trading it for a mystical femininity that has been denied and demonized. Casual sex and waged labor are held up as twin degradations that have resulted from feminism’s image of liberation. Sex and work are construed as damaging because they take women away from their natural roles—which are, ironically, sex and work, and in particular sex as work. Casual sex and work outside the home is ruinous, whereas marital sex and work inside the home is godly.

Sex is almost never directly mentioned, and when it is, it’s coded, often with a substitute homophone: “seggs.” “Seggs” has broader application as a euphemism that avoids platform censorship; it’s used by tradwives, sex therapists, and producers of sexually explicit content alike. It takes on specific connotations when used in the tradwife vocabulary, where its modulation of “eggs” evokes both the animal husbandry of homesteading and the procreative focus of conjugal relations. As a tradwife euphemism, it displaces sex twice—first as a word, and then as a bodily act. The topic often appears obliquely, when wives reference things like “the value of large families,” or the necessity of “serving their husbands.”

Sex might also arise, if indirectly, in the context of occasional self-conscious commentary on the tradwife image as a fetish. According to TikTok tradwife Estee Williams, men consume her content because they like the idea of a beautiful “feminine” woman waiting at home to serve their every need. It’s “natural” that they would feel this way. (Never mind that her content is also staged in such a way as to make her appear as though she is having a one-on-one conversation with viewers: her partner rarely appears, the camera is focused intently on her, she speaks in a soft and girlish voice that fits highly conventionalized depictions of what makes a woman desirable, and so on.) In the subsumption of sex into the regular course of household duties, the act is naturalized and theologized as a God-given duty akin to housework and child rearing. Whatever pleasure there is to be found in the experience will come only from the second-order frisson of conforming to gender roles.

In a recent article for Pinko, Max Fox wrote that sexual liberalism “takes the economic cleavages of the social and presents them as the outcome of private desires.” We are compelled into certain kinds of intimacy, but we act as though our desires come only from within: we choose our partners; we choose to marry and be monogamous; we blame ourselves if things turn bad; we pathologize ourselves for not wanting what we are told we should want. Despite the way that its content associates feminism with modernity and castigates modern living as a path to false and selfish pleasures, the tradwife media ecosystem nonetheless tends to support the idea that women just need to make the right choices—a pseudo-feminist claim that enables an anti-feminist position.

Tradwife ideology is a strange variety of theologized and racialized sexual liberalism: it naturalizes economic disparity through its investment in portraying rigid gender binaries as biological truth. It biologizes sex by imagining that only conformity with particular kinds of gender presentation and household divisions of labor is conducive to proper desire. And it calls these divisions Biblical, valorizing them as an answer to the dissolution of the family form.

If the archetypal tradwife is a white, Christian, conservative woman, the trend towards traditional marriage on social media is broader. As the tradwife media system has expanded, it’s also diversified. A more comprehensive study of tradwife ideology as it spans national, racial, and ethnic lines is necessary, though outside the scope of this piece. Worth noting, though, is that there have already been analyses of content by Black women who may not be self-identifying tradwives but whose posts resonate with the broader trad universe.

In 2022, Nylah Burton wrote about how some Black women online are appealing to “traditional marriage” and “Biblical marriage” as alternatives to white feminism and as a reprieve from overwork, economic insecurity, and anti-Black racism. Burton notes that marriage and the roles of wife and mother represent, to these traditional marriage proponents, a life formerly foreclosed by policies that forced Black women out of the home and into underpaid work, and that denied Black people the rights and privacy conferred to white couples through the marriage contract.

Insofar as marriage has been a social institution through which gendered labor, and therefore gender itself, has been organized, Burton notes that, for Black women today, traditional marriage can appear like a possible means of articulating forms of womanhood and femininity that have been denied through history. Put simply, if liberal feminism has promised freedom through work, such a promise has failed Black women, whose work has been the condition of unfreedom; furthermore, feminism has also failed to secure the integrity of marriage by forcing women into the workforce and contributing to the retrenchment of male workers and the crisis of masculinity. This has a specific significance for Black women whose independence is likely to be pathologized.

Henry and Victoria Doss, a Black couple who produce content together, offer a critique of feminism in these terms: in their straight-to-camera videos, they present Black women as oppressed by a feminist vision of liberation. Black women have been told that they do not need men, that their career is more important than family, and that sexual freedom is to be found in “hookup culture,” not in marriage. Yet because mainstream feminism is predicated on anti-Black racism, Black women’s liberation cannot be found independent of Black men and the Black family, or anywhere outside of the vision of marriage handed down in the Bible.

Across white tradwife media and Black traditional marriage media, economic crises are registered as anxiety about the breakdown of the family, with feminism and welfare policies largely to blame. This anxiety is borne out differently across lines of race, but it shares a fixation on gender and gender difference as the cause for political intervention. Part of this fixation centers on the notion that sex is critical for demarcating gender and differentiating roles in the family unit. Sex is what a wife gives and what a husband deserves, and yet both giving and deserving sex depend on a precarious balance of duty and desire that requires constant discipline.

As Jane Ward has written in The Tragedy of Heterosexuality, for as long as the privatized family unit has been the imposed norm and the most privileged mode, there has been a need for parallel efforts that attempt to get married couples interested in sex with each other. Advice columns, hygiene products, and film and television have all been part of a continued effort to facilitate intimacy between spouses (and in doing so, to direct intimacy away from same-sex sociality). Disgust, disappointment, resentment, and disaffection abound in heterosexual marriage as an institution, which is predicated not only on a gendered division of labor, but on a profoundly unequal division.

At the end of the 20th century, with the explosion of self-help books intended to give meaning to—and provide relief from—the seemingly intractable problems inherent to the couple form, the absolute difference between men and woman was held up as the primary cause of friction and the means through which harmony could be restored. To find peace and love in marriage required nothing less than seeing the other as a literal alien, from a different planet and therefore with a different reality. Venusians and Martians meet each other in the bedroom with radically divergent ideas about sex and desire.

Popular accounts of sexual desire have tended to rely on gendered differences as a given, and as the starting point for theorizing sex between straight, married people. One result is that a significant proportion of married women experience diminished sexual desire and satisfaction, a fact that is both pathologized as a disorder and naturalized as a mere effect of women’s sexuality. Women are harder to turn on, their desire is more elusive, their brains are not simply “hardwired” for sex like those of men. These common-sense ideas inform the medicalization of sexual dysfunction—and the appetite for pharmaceutical intervention.

Perhaps the most stark example of this is Flibanserin, a drug initially developed as an antidepressant that was approved by the FDA in 2015 to treat hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSSD) in premenopausal women. HSSD, considered the most prevalent Female Sexual Disorder (FSD), is characterized by “limited or absent sexual fantasies or desires, resulting in interpersonal strain or heightened distress, which persist for a minimum of 6 months.” Flibanserin works on specific serotonin receptors, modulating brain activity that is understood to regulate libido. The drug was advertised as effective precisely because it targets the brain.

Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: Viagra works on his penis, Flibanserin on her mood. The campaign for FDA approval was not without its controversies. Some critics pointed out the biases in trials, showing that it was far harder to get Flibanserin on the market than Viagra; others highlighted the possible side effects and some of the more restrictive conditions of the drug—for example, its negative interaction with alcohol and the need to take it at “bedtime” because of its sedating effects.

Proponents of the drug, on the other hand, used the language of “facts versus feelings” to show that the drug works by correcting what has been referred to as “bothersome low sexual interest.” Across the discussions, there is a conspicuous absence of the obvious question: why, exactly, this bothersome low sexual interest is so rife. Why is sex, so to speak, so depressing for straight women?

Marxist feminism has attempted to answer this question through an analysis of sex as part of the unpaid work necessary for the reproduction of labor-power. Despite being coded as natural and ambiguously “outside” relations to capital, sex is in many ways mediated by capital and understood according to a gendered division of labor. Seen in this light, sex is, for women, an act of devotion as well as a procreative necessity; for men, sex is relief from waged labor and the means through which paternity is secured.

In her reading of the Marxist feminist archive, Chelsea Hart recently argued that labor militancy among sex workers illuminates the work of sex in heterosexual relations under capitalism. Hart reads Silvia Federici’s 1975 “On Sexuality as Work,” in which Federici similarly argues that one effect of the naturalization of women’s care work is that sex for love and sex for money appear absolutely opposed, when in fact they are separated only by the fact that the latter is paid.

Hart writes: “Rather than see female sexuality as something inalienable, and in need of protection from commodification, the perspective of autonomist feminists has long been that sexuality is itself a working condition, and that sex work occurs constantly outside of the sex industry unpaid, and in the service of capital.” Sex in the service of capital has come to be defined by a set of gendered assumptions about desire and duty. Men need sex, whereas women want to please their husbands and keep their interest; men are hardwired for physical pleasure and women for emotional connection. Sex is something that women give out, give up, and give into; sex is something that men are perpetually driven towards, motivated by, and able to be manipulated with.

We have been arguing that the ideology of the tradwife is a new solution to an old problem: how to encourage women to have sex with their husbands, or rather, how to encourage women to want to have sex at all. But though it trades on very old symbols, its newness matters—it emerges in concert with a conservative media landscape that is rife with racialized anxiety about how to sustain a particular national social order in the face of declining white birth rates. This order is perpetuated by traditional heterosexual marriage, sanctified binary gender roles, and respected parental authority. Any failure to produce babies (especially when other people seem to be having too many!) perfectly manifests the breakdown of this existing regime, encouraging a bunker mentality that uses the specter of social disorder—the upending of white dominance—to shore up borders and impose authoritarian rule.

Young people in wealthy countries are not just having less sex—they’re also having fewer children overall. Proponents of the white nationalist theory of a “great replacement” fear that migrants are being “brought in” to substitute for declining white populations and to fill jobs in increasingly precarious labor markets. In this particular fantasy, anxiety about the collapse of industrial profit is projected onto the racialized other. In addition, a new set of fears, which Quinn Slobodian, writing in The New Statesman, has dubbed “no-replacement theory,” has recently appeared: the still-more catastrophic possibility of “a world without humans.”

Conservative media charges that leftists have drummed up fears of climate collapse to prepare us for this bleak anti-future—a claim that’s often paired with a correlation between falling birth rates and women going out to work. They maintain that people without children are “anti-family” and blame feminists for encouraging women to be breadwinners instead of housewives. From this vantage, having fewer babies and less heterosexual sex is a sign of generalized sexual dysfunction that is connected to the erosion of a culture of white dominance. To reactionaries, lower birth rates are proof of a perversion of nature and the subsequent breakdown of gender roles; a declining number of white babies in particular portends civilizational collapse.

Jason Smith, writing in The Brooklyn Rail, has suggested that one response to anxieties about demographic decline will be intensifying violent misogyny that deems childless women “narcissistic and against life”—they will be “shunned and shamed,” he argues, “not just by their communities, but directly by the state.” Anti-abortion laws are one instance of this; J.D. Vance’s idea that people without children should have to pay more taxes is another. In previous writing for Verso, we theorized the rise of tradwife media as one aspect of a broader counterrevolutionary campaign that champions traditional marriage and household formation. Weaponized fears of white demographic decline have shaped this campaign, which promises to both end the fertility crisis and to release heterosexual people from the perils and ambivalences of contemporary intimacy.

Tradwife content associates traditional gender roles with a healthy society devoted to family life. Gender nonconformity is, in contrast, selfish, empty, anti-family, and devastating for lonely men. The tradwife is a figure uniquely capable of solving the twin crises of masculinity and declining white birth rates: her commitment and care, manifest in a particular style of submissive self-presentation, is a prophylactic against widespread emasculation, alienation, and social disorder. One woman devoted to one man redresses the problem of women and men meeting each other on equal terms, at work and in the home. It also carries a libidinal charge as the Lord’s work of reproduction—a means of defending white Christian culture from etiolation and decay.

But a different response to demographic decline is also possible. When households are no longer primarily responsible for reproducing the labor force, their boundaries become more porous and frayed—and this is a good thing. As Jason Smith also imagined in his piece for The Brooklyn Rail, the activity of making life could become more genuinely socialized, with care for people at all stages of existence distributed across large social clusters. Among the results: people would not need to fear that childlessness would leave them bereft of company in old age, and, as Smith put it, “children would no longer be fetishized or adored as emblems of futurity, or as sites for projecting fantasies of vulnerability and innocence.”

A declining population is indeed a measure of a profound shift, one that is already underway, in the mechanisms of social reproduction. Smith observes that “the core institutions of capitalist society—the family, state, and private property,” are vulnerable to demographic change. This is why reactionaries will go to such great lengths to contest it. Tradwife media has arisen as an outgrowth of these ideological necessities; it forms part of a defensive infrastructure.

This new permutation of very old hierarchical legitimation openly links a feminist insistence on women’s equality with gender nonconformity, “woke” education, and abortion rights; more libidinally, though, no matter how its particularities shift, traditionalist ideology is consistently focused on rehabilitating beleaguered but stalwart institutions. In the tradwife’s appeal to submission, we read an unconscious admission that the crisis she is tasked with fixing—the lack of desire, lack of sex, lack of babies—portends the arrival of a reality she finds intolerable: the end of the age of white dominance. ♦

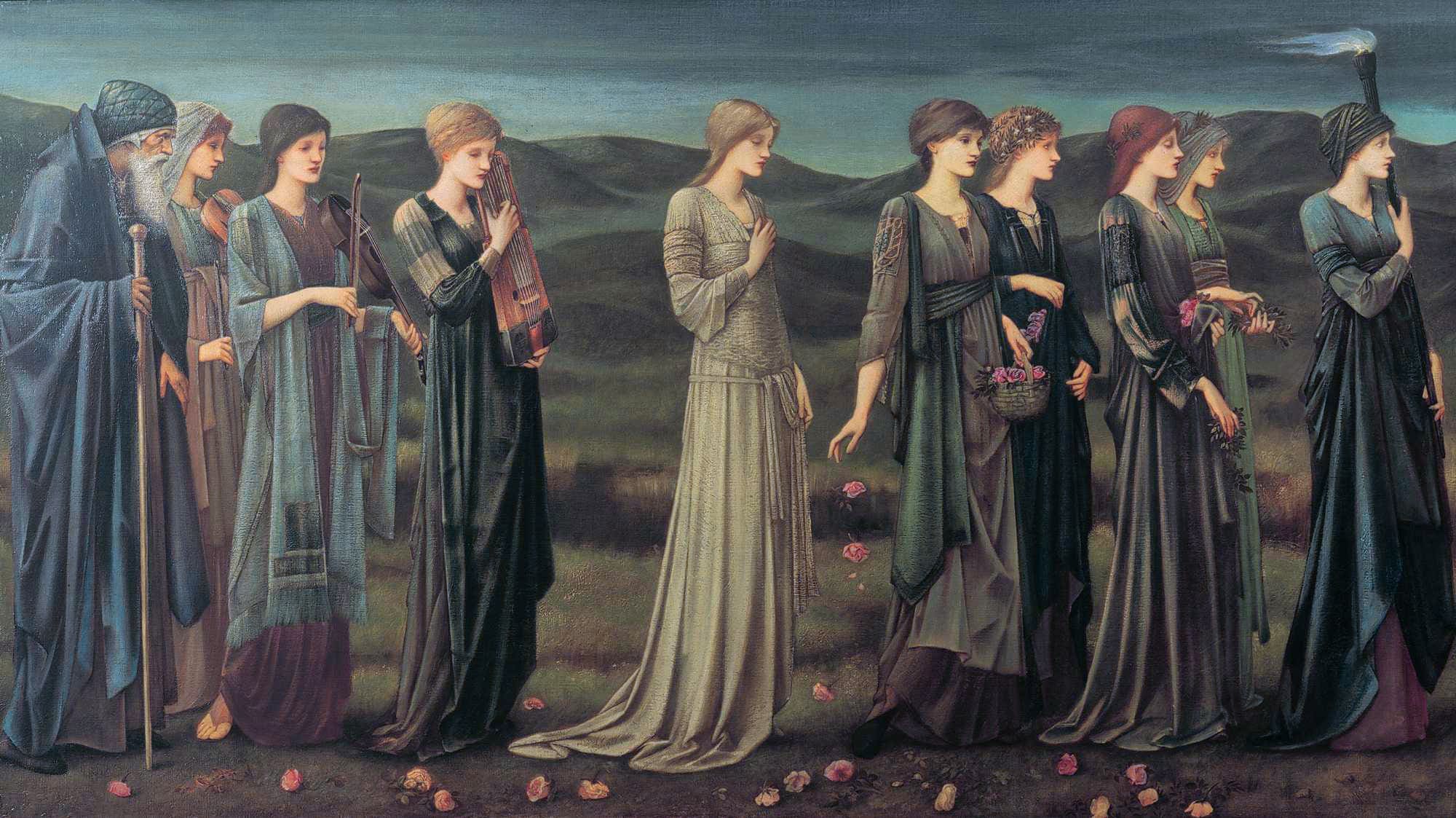

Cover image: The Wedding of Psyche, Edward Burne-Jones (1895).