這是真的。 The following is true.

So begins “Love” (愛), an obviously fictional short story written in Chinese by the prolific author and feminist thinker Zhang Ailing, better known as Eileen Chang (1920-1995). Chang’s work has been the subject of some academic and political controversy, but for what it’s worth, I remain rather attached to it. “Love” was the first story I could read in Chinese, and Chang’s essays and novels helped ease me into a linguistic and literary world in which, to be honest, I still feel some discomfort situating myself as a reader, let alone a member. Through her writing—and the meta-controversy surrounding her choice of language and home—Chang presents a truth that I still can’t shake, no matter how much I interrogate my own personal sense of Chineseness: that the “authenticity” of identity is itself a fiction, impossible to define or create.

Though she has frequently been identified as a Chinese writer, Eileen Chang’s long literary career evinced an often-thorny relationship with the concepts of China and Chineseness. Well-read in both the Anglophone canon and the Chinese classics, Chang wrote alternately in English and Chinese at different stages of her life, including for an organ of the Cold War-era U.S. propaganda apparatus. She studied English literature at the University of Hong Kong and left China roughly a decade later, never to return; from there, she went on to become an American citizen and taught at American universities. Even Chang’s name bears the marks of her complicated identity–born in 1920 as Zhang Ying, it wasn’t until her late childhood that she was renamed “Aìlíng,” a Chinese transliteration of the English “Eileen.”

These facts of Chang’s life have led to significant controversy over the national and cultural identity of her work, including an interest in questioning Chang’s “Chineseness” that often serves as a proxy for more generalized questions of how we judge cultural authenticity at all. A number of Chinese literary scholars have argued that the privileging of Chang’s work was the beginning of a mid-century attempt by Taiwanese and diaspora critics to rewrite modern Chinese literary history, shifting it from its traditional focus on mainland China. Likewise, the intellectual historian Jing Tsu somewhat ambivalently identified Eileen Chang as a “Chinese Anglophone” author, citing her desire to “project herself in and across two languages [for] reason[s] she never quite explained” and the marked feelings of “unease, if not… guilt and betrayal, over writing in the English language” that are occasionally evident in her work.

I accept these accounts of Chang’s writing; they are, I think, self-evidently true to anyone familiar with her corpus or its place in Chinese literary history. But whatever scholarly difficulties may have resulted from Chang’s inability or unwillingness to explain her attachment to bilingual (and by extension, transnational) practices, I remain sympathetic to her decision to leave her motivations a mystery. So much of the so-called “Chinese-American” experience remains inexpressible that, in certain situations, it seems better to remain silent.

Growing up where I did in the United States, my Chineseness clung to me like a shadow, the occluding object just out of sight, observable only by the contrast it struck with everything around me. My Chineseness was obvious, the first thing people noticed about me—and its absence was unimaginable, no matter how much my surroundings tempted me to wonder what life might be like without it. I learned the word “Chinaman” almost as soon as I was first enrolled in an English-language school. The label stuck, to my dismay, even after I quickly shed my native Cantonese accent and my Chinese language abilities began a years-long process of slow decay.

At seventeen, I remember standing in costume for a play, a girl in front of me flirtatiously tapping the plastic armor on my chest.

“You make a dashing knight.”

“I think I need a title,” I joked. “Don’t knights have titles? I feel like we read that in a history class.”

“Okay,” she said, brightly and without hesitation. “You can be Sir Asian.”

Temporarily short-circuited, I paused, and she changed the subject.

Even when my Chineseness appeared to recede, its absence was a matter of specific concern. The same year I gained the dubious honorific of Sir Asian, I sat across a table from someone who, I soon realized, thought of me as their date for the evening. “You don’t look fully Chinese,” they remarked, leering in a way that I now understand would have seemed much more unpleasantly familiar had my Chineseness not been attached to a male body. I suspected, given the context, that this was supposed to be a compliment. After a short delay, they smiled and popped in with a correction. “Maybe half.”

I wondered if that was something I was supposed to want: to look not-Chinese, or at least only “half.” In any case, it never really mattered. My upbringing had already left me quite attached to the idea of being “Chinese”—although at that time only in a generalized and ahistorical sense—and when your face looks like mine, it becomes difficult to differentiate liking “Chinese” things from wanting to be Chinese.

It was not long before I found myself grasping at Chineseness, the desire enmeshing itself within imperfect attempts to sharpen my Cantonese and a budding fascination with Chinese history and literature. “Chineseness” revealed itself to me, often shallowly and falsely but no less alluringly, in glances and fragments—conversations under the harsh fluorescent lighting of a Hong Kong café, a line of a poem I knew by heart but couldn’t read, the film-grain smoke and staircases in a Wong Kar-wai film.

I reached for essays, short stories, and eventually novels written in Chinese—even as I remained mired in a sludge-like mix of traditional and simplified characters, which slowed my reading and frustrated any budding feelings of authentic association every time I traveled to Hong Kong or the mainland. I considered using variations of my Chinese name more openly—though it had been mocked frequently throughout my childhood, rendered in bizarre permutations by classmates. Eventually, I decided that (like a friend of mine who, at the beginning of college, made an abortive attempt to initialize his first name, in Northeastern WASP fashion) this was maybe too obvious of a play for sociolinguistic belonging—just in the other direction.

The critical theorist Alberto Toscano once posited that the idea of “China” served, in the Western political imagination, as an “allegorical country,” a country and a history understood imprecisely as the home of “a distinctive configuration of human possibilities, but also a vast and distant screen on which to project.” I think that “Chineseness” can serve much the same purpose for the ostensibly Chinese individual, situating them within the scope of a much larger ideational whole that functions as a sort of cultural and psychological Rorschach test. In the mainland, “Chineseness” might mean the Chinese Dream; in Hong Kong, techno-dystopia and linguistic integration; across the straits, alternating dreams of revanchist republicanism and fears of incipient threats to an independent Taiwan.

So what does “Chineseness” mean for the diaspora? If my own experience is indicative of anything, it’s probably a sense of cultural alienation and a set of identarian conditions marked by having less political and philosophical security than one would like. But perhaps it also relates to a desire for a novel configuration of the self, one that’s connected to a type of alien authenticity that societies in the United States, China, and elsewhere have often insisted must lay dormant deep within us. We are expected (with suspicion in America, and in China impatience) to somehow “be” Chinese at our core, to speak the language naturally and know the culture comfortably.

People in both the U.S. and China have taken to referring to Chinese-Americans as “American-born Chinese,” a label which would be at least moderately shocking in any other context. (Imagine, for a moment, a putatively cosmopolitan person calling Barack Obama an “American-born Kenyan.”) That many people in my situation do not feel authentically Chinese—and often cannot even imagine what it would be like for that to be the case—does not really matter. We are encouraged to want to be properly Chinese, and often do want it, even as the prospect remains more or less impossible.

Eileen Chang herself alludes to this impossibility in her writing about seeking refuge in historical consciousness. In a 1944 essay titled “Writing of One’s Own” (自己的文章), Chang notes how the aspiration to see oneself as authentically connected to a civilizational past serves to distort one’s views of the world:

“[When] we feel we have been abandoned… we seek the help of an ancient memory, the memory of a humanity that has lived through every era, a memory clearer and closer to our hearts than anything we might see gazing far into the future. And this gives rise to a strange apprehension about the reality surrounding us. We begin to suspect that this is an absurd and antiquated world, dark and bright at the same time.”

What strikes me about this passage is not only Chang’s belief that cultural or civilizational mythologizing is a corrosive force, but also her understanding that this force arises from the same type of isolation that it creates. Those of us living under the shadow of Chineseness face expectations of linguistic competence and demands for cultural loyalty; any attempt to live up to these standards can only leave us with the same sense of inauthenticity that led us to reach for Chineseness in the first place.

The problem of encouraged and yet hard-to-grasp authenticity crops up frequently in discussions of public figures who spend their lives flitting between zones of American and Chinese identification. This relatively small but attention-drawing group of individuals includes not just its ne plus ultra Eileen Chang but also another Eileen—the exquisitely talented skier, model, and two-time Olympic gold medalist Gu Ailing.

Gu, a U.S. citizen, emerged as a breakout star in the 2022 Beijing Olympics, where she chose to compete as a member of the Chinese national team. This decision led to a flurry of nationalist recriminations and handwringing over her identity. But in spite of the controversy, Elieen Gu has become a phenomenon in both the U.S. and China, with legions of fans in both countries. Her face appears on Chinese magazine covers and American energy drink advertisements; her interviews draw significant positive attention on both American and Chinese social media.

In many ways, this makes sense. For whatever hay nationalists on Weibo and politicians on Fox News try to make of her identity, Gu’s life story is tailor-made for international celebrity status, marketable to consumer audiences in both countries. She grew up in a wealthy neighborhood of San Francisco, received her education at prestigious American private schools, and does not appear to ever have lived in China. For some years, she represented the United States in various international skiing competitions. But at the same time, she can make an authentic claim to Chineseness—she seems to hold Chinese citizenship (possibly in tandem with her American passport), she has traveled to Beijing frequently throughout her life, and her Mandarin, spoken with a distinctive Beijing-area accent, is fluid and fluent. Asked about her identity, she answers simply: “Nobody can deny I’m American, nobody can deny I’m Chinese… When I’m in the U.S., I’m American… when I’m in China, I’m Chinese.”

The marketing in China surrounding Eileen Gu’s stardom feels underwritten by a desire to see the ambiguities and difficulties of Chinese-American identity smoothed out by market forces and a type of bland, commercialized transcultural interaction. Gu’s boosters acknowledge as much: “With her model looks, her fluency in Mandarin, and her ability to compel millions of Chinese viewers to care about the Olympics,” wrote one reporter, “there was no limit to the magnitude of what she could become [or] what products she could sell.” If it were happening in the United States, this type of marketing might be referred to as a kind of “boba liberalism,” a pejorative that denotes Asian-Americans who are committed to generic representation politics, shallow engagement with the consumerist trappings of Asian-American identity (bubble tea, Korean barbeque, dim sum brunches), and inattention to the specific contours of the cultural and political problems faced by Asian diaspora populations.

The emergence of “boba liberalism” represents a bleak (and, frankly, delusional) solution to the problem of Chineseness: a hope that American society, aided by its particularly robust and assimilationist local variety of capitalism, will swallow up “Chineseness” and spit it out as a set of inoffensive consumer choices and aestheticized commodities. Eileen Gu’s stardom in China is merely an analogous thought process, transplanted across the Pacific. Never mind the complicated politics of the circumstances that could lead a fabulously wealthy Chinese-American athlete to switch between competing for the United States and China, much less the fact that, for all her glibness on the matter, even Eileen Gu cannot escape being considered Chinese in America and American in China. It is one thing to sell a product successfully in China or America; quite another to belong in either of those places.

Many Chinese-Americans want more than a transnational commodification of Chinese-American identity, desiring an intercultural experience that goes beyond a T-shirt or a punchline. It’s distressing to imagine that something as complex as identity could be reduced to aloof parents and “Asian Fs,” boba tea and the battle hymn of the tiger mother. Still others may find the sort of ultra-wealthy lifestyle undergirding the cosmopolitan celebrity of people like Eileen Gu off-putting. Even if one accepts that splitting time between the U.S. and China by way of Stanford, the Olympics, and an international modeling career is somehow a means of avoiding the ugly realities of alienation and identarian confusion—what’s the average Chinese-American supposed to do with that?

In any event, this may not matter at all. Many of us consider the possibility of slow capitalist integration scarcely imaginable given the increasingly racist tilt of American politics, which—as the United States and China begin to see each other less as competitors and more as outright enemies—has developed a laser-like focus on the loyalties and political boundaries of Chinese-Americans. That’s not to say that the commodification of Chinese-Americans has stopped happening (or ever will); as Eileen Gu’s case shows, it is indeed occurring on both sides of the Pacific. But the racialization of the same people who are subject to commodification continues apace, and in a way that ensures there will never be a Chinese equivalent of the “Kiss Me, I’m Irish” T-shirt. Almost invariably, white Americans won’t need a shirt slogan to suspect that we’re Chinese, even if they’d want to kiss us more if we only looked “maybe half.”

Embedded within this matter of identity is a subsidiary problem of desire that pervades Chinese-American life. By this I don’t mean the problem, explored abundantly and lyrically by writers like Eileen Chang, of how cultural and political and racial circumstances warp how others desire us. Rather, I want to plumb the depths of what we as Chinese-Americans want for ourselves, unremarkable as these feelings may be to those of us living them. Years of celebrity thinkpieces and diaspora poetry and prettily curated Instagram graphics have primed us to think that the problem of the Chinese-American experience centers around a deep desire to just be American. (Or more rarely, to just be Chinese.) But the fact—lonelier and more unpleasant to grapple with—is that when I look around at faces like mine, what sticks out isn’t really a desire to be Chinese or American. Instead, I can’t help but see a deeply felt longing to be anything at all.

For me, this problem persisted, no matter how much more comfortable with Chinese language and culture I became. As my involvement with politics in both Hong Kong and Asian America grew, I started looking for solutions in alternatives to Chineseness. The increasingly nationalist and irredentist lean of the government in mainland China—as manifested in crackdowns in Hong Kong and threatening military flights over Taiwan—has spawned a multitude of political responses, among them an acceleration of certain divergences in Hong Kong and Taiwanese identity that had been slowly developing for decades. Significant resistance to the idea of the dazhonghua (“Greater China” or “China proper,” defined roughly by the borders of the old Qing empire) now exists among a variety of ostensibly Chinese populations, many of whom seek to define themselves against the idea of “China” as a political or cultural matter. When protests in Hong Kong flared up in the 2010s, “I’m a Hong Konger, not Chinese” became a common, if controversial, slogan. At the time, I was still juggling a Hong Kong residency with an American passport. I’d thought, based on those facts as much as my linguistic and family ties to the city, that I might have some basis for associating myself with that developing political identity.

The logic behind these political alternatives to Chineseness is simple and compelling. Hong Kong and Taiwan experienced the 20th and 21st centuries in vastly different ways than mainland China did—much in the same manner as territories inside the so-called dazhonghua experienced the 18th and 19th centuries in vastly different ways than those outside. If we understand the latter historical circumstances to have helped create the notion of a specific Chinese identity, we must also understand that there is no compelling reason why the former could not create one, or two, or indefinitely many emerging identities, whether in Hong Kong or Taiwan or elsewhere.

This is a productive line of thought, but it didn’t quite solve the problem of authenticity for me. These days, I conceive of myself as a Hong Konger-American of some sort, to more or less the same extent that I think of myself as Chinese-American. To me, this duality seems politically healthy—a move towards considering “Chinese” as a cultural rather than national label, closer to the generalized “European” than the specific “French.” But the same problems pursued me even as my identity relocated itself across the Shenzhen Bay. If living as a Chinese-American meant accepting uncomfortable feelings of alienation and inauthenticity, being a Hong Konger-American, or Taiwanese-American, or anything else in that vein just means accepting a different set of uncomfortable realities: putting “native fluency” next to an HSK level on your resumé, staring blankly when you hear a Cantonese or Min Nan phrase that’s too colloquial or not colloquial enough, shifting in your seat and admitting you went to college, high school, and even, yes, elementary school in the States. Try as we might to deny it, displacing one’s identity usually just means displacing one’s problems to a new location.

There are theorists who believe in a vision of Chineseness, if it can even be called that, that covers not only people like me but also a broader swath of populations whose historical contacts with Chinese empire have left them with recognizable traces of the Chinese cultural imprint—Hong Kongers, Taiwanese, Hui, Tibetans, and Mongolians, but also groups of so-called “ethnic Chinese” in Indonesia, Vietnam, and elsewhere throughout East Asia and the world. Shu-mei Shih, a cultural theorist and literary scholar whose work is situated within the broader field of Chinese-language studies, has offered the most well-known account of this. In keeping with the postcolonial thinkers who fleshed out the “Francophone” and “Anglophone” concepts, Shih posits the existence of a “Sinophone” identity, one which identifies its subjects as the peoples and cultures on the margins of China and Chineseness. In her telling:

“The Sinophone peoples are closer or farther from China, Taiwan, or Hong Kong, or the other Sinophone sites in Asia… depending on their perceptions of both geographical and psychic space. In their rootedness in the local places, the Sinophone peoples across different oceans and territories negotiate the relationship between space and place creatively.”

“Sinophonicity” does not really seek to replace Chineseness, but instead attempts to render moot its assumptions of a single, definable identity. The idea of the Sinophone tells us what we are all dimly aware of but are unable to accept within the frame of Chineseness—that very few people really feel Chinese or anything adjacent to it; that everyone’s Mandarin has a regional accent; that it’s exceedingly difficult for anyone anywhere, within and without the borders of the dazhonghua, to navigate problems of nationhood and belonging.

This is, in a way, comforting. When I first read about the Sinophone, I tried to embrace it, drawn in by the blurriness of its boundaries and its forward-thinking conception of identity as delineated by what Umberto Eco might call “family resemblances” rather than specific markers. I still try, more out of a sense of linguistic precision than political commitment, to use the term in conversation. But as much as I would like to, I cannot find in the Sinophone a solution to the problem of “Chineseness,” either.

Whether someone is or is not “Sinophone” seems to be a diagnostic matter: you are Sinophone if you are an ambiguously Chinese person who speaks some form of the language. All categories are, in a boring sense, historically contingent, but the Sinophone is designed explicitly with that fact in mind; this is, I suppose, a way to circumvent the squishiness of liberal identity politics. Being a Sinophone-American is something you are born as, but also something you choose to keep. As Shih notes, “the Sinophone exists only to the extent that [Sinitic] languages are somehow maintained,” even if that maintenance involves the “outright abandonment of any ancestral linguistic links to China.”

But how much does the choice to keep a language mean? In many cases, very little. People may retain some facility with Chinese for any number of reasons: to talk to their parents, to help their careers, or simply because the language never managed to slip away from them in the first place. In an academic sense, Sinophonicity may encompass any number of individuals who do not actually speak Sinitic languages well or know Sinitic cultures meaningfully. But in a practical sense, it seems almost cruel—an imitation of the sort of cultural-nationalist grouping the ”Sinophone” label explicitly seeks to counter—to insist sticking this label on someone who, by intention or neglect, knows little or nothing about the language, history, and culture of the so-called Sinophone world. It may at times allow for a sense of belonging, but it’s forced. To the extent that Sinophonicity solves some problems of identity, it echoes the problem of the dazhonghua, lumping together people seeking an alternative to Chineseness with those who don’t want to think about it at all, creating a category that is at once too narrow and too wide.

Scholars such as Jing Tsu have criticized the Sinophone concept on the grounds of this narrowness. “Whatever appeal Sinophone studies now has,” she writes in her book Sound and Script in Chinese Diaspora, “it will need to establish stronger dialogical roots in the long history of diaspora and migration in all its disarticulated forms.”

I agree with Jing Tsu when she says that the Sinophone concept must expand. But in my mind, the real problem with being “Sinophone” isn’t the aforementioned issue of the label being too limited or too voluntary. It’s that, at least for now, no one wants to be “Sinophone,” because wanting to be Chinese, or American, or anything at all isn’t really about a label, whether nationalist or notional and academic. People are drawn, like I was, into pursuing Chineseness and its alternatives by Eileen Chang and Wong Kar-wai and Ma Jian and Hu Shih and Yan Lianke, by dinners where you don’t have to pass the plates, by pushing red packets back and forth, by the distinctive sounds of Cantonese opera, by Tang poetry, by the idea that you might have a team to root for that wouldn’t question your membership just by looking at you, by the thought that you could latch onto a way of conceiving of yourself that doesn’t raise a million awkward questions whenever it’s uttered out loud.

You might wonder how this differs from the boba liberalism I mentioned earlier, those shallow trappings of cultural identity that I dismissed as consumerist red herrings. I’d like to tell myself that my aesthetic interests are deeper, that they allow me to experience not just what I can buy, but also shared artifacts and sensations that authentically belong to me on identarian and cultural grounds. In any case, I acknowledge that it’s possible I’ve backed myself into territory I cannot defend. I understand, intellectually, that it’s not productive to think that one can experience these things with any sense of realness; I will even argue with relative sincerity on any day of the week, in any public setting, that the mere desire for a “real” experience is a backwards acceptance of nationalism and exclusivism.

What I’m describing here may seem like the acknowledgement, or even flattery, of an unreal reality—and a frankly unseemly desire for belonging and cultural possession. But it remains a real desire nonetheless. Perhaps scholars in the emerging field of Sinophone studies will figure out a way to reconcile these contradictory impulses, drawing on a deep intellectual foundation of transnational solidarity and the diverse history of the Chinese linguistic and literary tradition. But when it comes to the application of logical intellectual principles to irrational wants, I won’t hold my breath.

“When you really want something, contradictions matter less,” writes the anthropologist Danielle Carr in an essay about plastic surgery and socialized healthcare. “Desire doesn’t say yes or no, it holds two irreconcilables and says ‘and yet.’ I’ve learned to call this a dialectic.” Call it a dialectic or not, I don’t care. Desire works the same way, whether it’s identity or beauty or anything else. I wish I could figure out my Chineseness, even as I know it’s not possible, nor even really desirable, to do so.

In her writing, Eileen Chang spoke only infrequently and obliquely about problems of national and cultural identification, even as she wrestled with them throughout her life. But in her essay “From the Ashes” (燼餘錄), she provides some musings on the futile vanity of self-identification and personal narrative as part of a broader consideration of her time in Hong Kong during the Second World War.

“What a shame that we occupy ourselves… searching for shadows of ourselves in the shop windows that flit so quickly by—we see only our own faces, pallid and trivial. In our selfishness and emptiness, in our smug and shameless ignorance, every one of us is like all the others. And each of us is alone.”

Chang’s writings about wartime Hong Kong occasionally mock the notion of self-fictionalization; most famously, in a novella about an affair that takes place during the Japanese occupation, she pokes fun at the idea that a brutal and catastrophic war might ever be thought of as the backdrop to some couple’s mediocre romance. But at the same time, Chang spent much of her career engaging in this very activity of self-imagining, including by her own acknowledgement—at various points in her work, she openly tells her readers that she is one of the people whose inclinations and desires her writing seeks to satirize. In the literary critic David Der-wei Wang’s telling, “Chang seems to suggest… that if she could only learn her family history through a novel… it makes equal sense that she could write her own experience back into fictional forms.” Her entire oeuvre, he argues, “stems as much from her confessional urge as from her desire for self-fictionalization.”

The desire for self-fictionalization, the interest in personal narrative, the longing to see your own story told in a way that makes sense: this is the core of the problems of identity and authenticity that delineate the problem of Chineseness. To borrow Chang’s metaphor, we may think of Chineseness and its counterparts as fictional mirrors, shop windows that we peer into, knowing they will distort our image. Is this irrational? Of course. Damaging, too. But why not look? There are simply no other surfaces upon which we can see ourselves. ♦

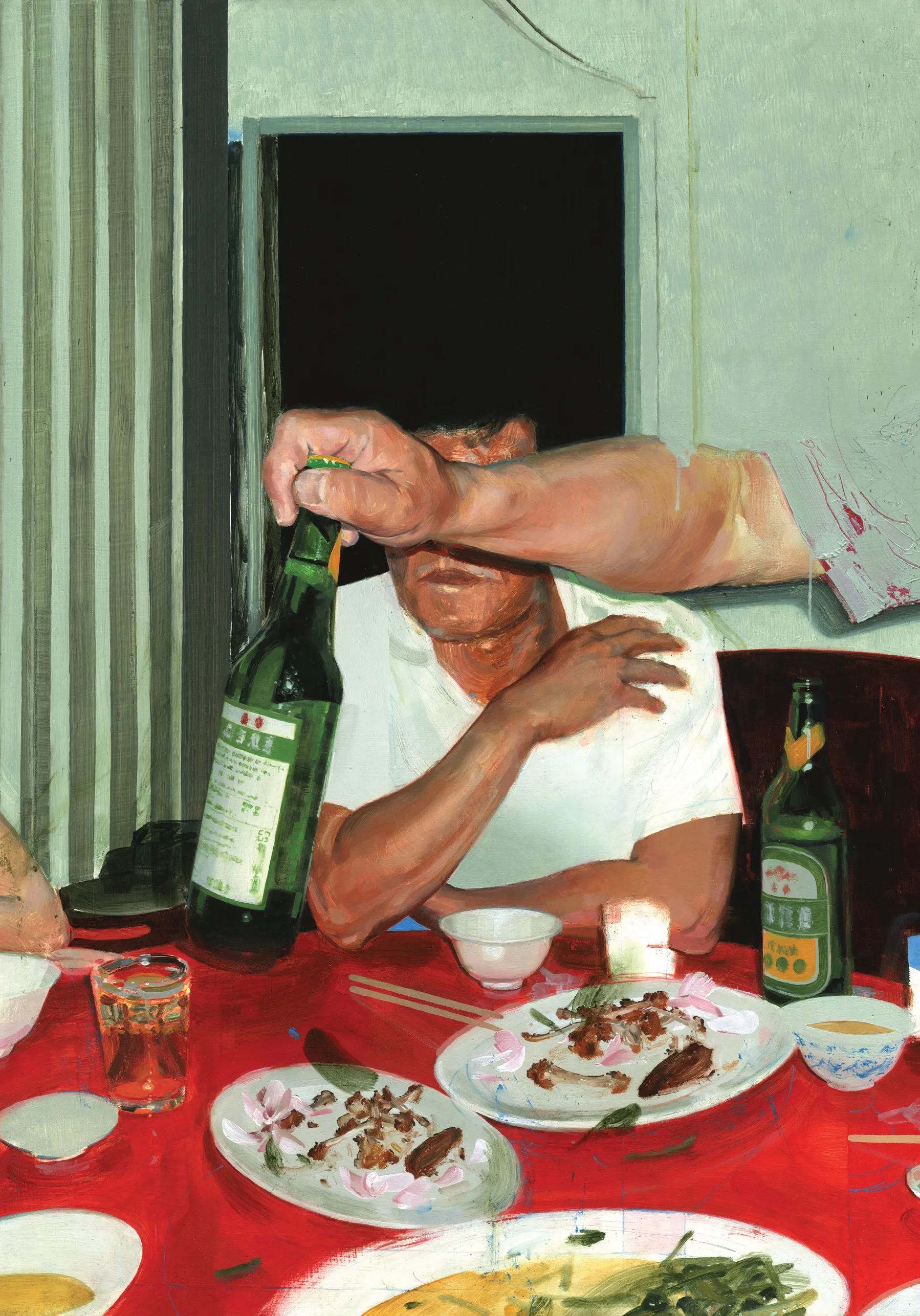

All images by James Lee Chiahan. Cover image: “Crazy, Happy, Foolish, Fleeting.”/ First image: “As two petals fall.” / Second image: “Banana.” Licensed with permission.