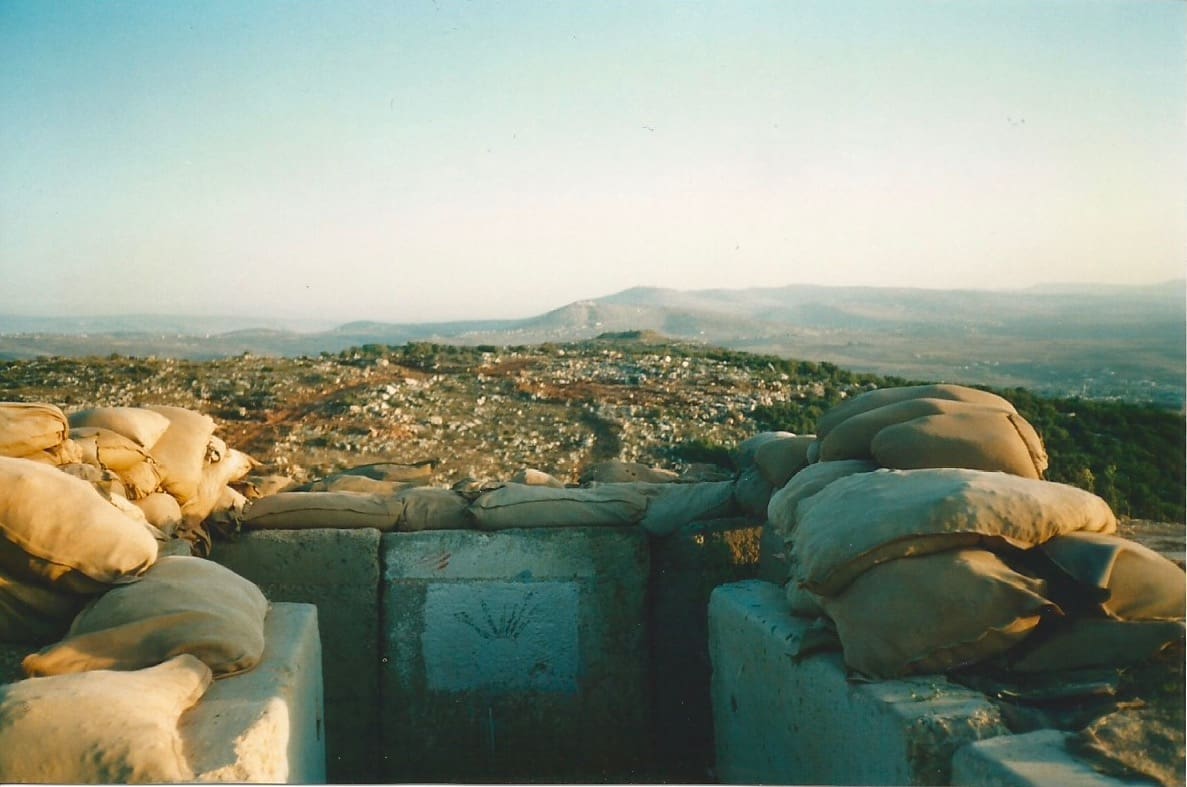

During the July War of 2006, the Israelis decided to plant their flag in the Lebanese town of Bint Jbeil at the site of the speech that inaugurated Lebanon’s liberation from Israeli occupation in May 2000. Despite the enormous damage wrought upon Lebanese civilian infrastructure, the July War was not going well for Israel, and the flag-planting operation would be a symbolic stunt to boost Israeli public morale. To reach Bint Jbeil, an elite Israeli brigade set out from a nearby settlement called “Avivim.” I’ve retained these details—and that the operation was unsuccessful.

In recent weeks the bombs dropped onto Lebanese homes and fields, seeping toxins into the soil, have been answered by volleys of missiles targeting Israeli military sites in various settlements. “Avivim” registers differently for me than does elsewhere across the Blue Line (as an expansionist project, today Israel technically has no declared border with Lebanon, just a “line of withdrawal”).

Avivim: to let pass without friction a nomenclature premised on my people’s erasure, because this is what they call it now, feels like a sort of surrender. Every time it’s mentioned, I think of my grandfather, and what it took from him. Not the word, exactly, but the world it sits in. What they call “Avivim,” built atop my great-grandfather’s grave, we call Salha.

The timeline starts some decades back: in late October 1948, Salha’s inhabitants were forced out by massacre. One hundred people—men and boys, mostly—were lined up and shot, one by one by one. A couple of the injured played dead, their act aided by the paralysis of fear. Those who, thanks to the Zionist soldiers’ failed aim—or, the survivors might say, divine intervention—were not struck, also played dead. When the soldiers left, survivors gathered whomever they could. Some of those who’d initially fled risked their lives to return and look for their families. Some struggled to bury their dead before the killers returned with bulldozers. A young woman carried her wounded father on her back for three kilometers—to Bint Jbeil. He, for his remaining years, would let no one forget that he owed his daughter his life.

An eleventh of the village was executed. The rest, including my grandfather, his sisters, and his mother, fled north across a freshly imperforate border into southern Lebanon. As neighboring border villages caught word of the massacre (what Zionist troops called “whispering operations,” in service of their systematic psychological warfare campaign to empty the land of its inhabitants), these too were “depopulated”—ethnically cleansed.

Survivors stayed with family, or they rented homes, or, as winter came and left and Return remained prohibited, they continued north to refugee camps like Sabra and Shatila in Beirut. This is how some one quarter of those killed during the Sabra and Shatila massacres—orchestrated by Israel just as soon as the armed Palestinian factions were evacuated from Lebanon, leaving Israel’s ever-civilian targets without defenders—were Shia Lebanese nationals. Many of them had fled Salha and other border villages during the Zionist terror campaigns of 1948, and sought refuge in the camps. Others fled the terror campaigns of 1978, still others those of 1982, and so on. Sometime after Salha was emptied—after my grandfather, barefoot and eleven years old, learned to work someone else’s fields to supplement his mother’s income as a seamstress—came the name change.

Israeli historians are incentivized by national self-conception to believe that upwards of three quarters of a million Palestinians left their homes voluntarily in 1948, of their own volition or as sheep herded by their Arab leaders. Against this impossible narrative emerged a group of Israeli scholars calling themselves the “New Historians,” most prolific among them Benny Morris, bound by the shared belief that the Nakba (as in, forced dispossession) happened at all.

In The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Question, Morris explores “how and why” Palestinians became refugees. He conceives of history as an exercise in moderation, where truth is a middle ground: despite what the Israelis claim, mass forced displacement did occur; despite what the Arabs claim, it was not premeditated or systematic. This “transfer” (a well-worn euphemism for ethnic cleansing), Morris concedes, was “inevitable and inbuilt into Zionism,” “accepted as “natural…by the bulk of the Jewish population.” Morris’s project, as described by the scholar Norman Finkelstein in a book review of Birth, was to replace one myth—the myth of voluntary emigration—with another, that of impromptu and uncoordinated forced dispossession.

Taped to the entrances of various mosques and husseiniyehs (Shia mourning spaces) in Lebanon today are lists of the 105 martyrs, including their names and ages, killed during the Salha massacre. People with families who had to grieve and redeem their lives and mostly, carry on. As part of my master’s thesis research, I constructed an oral history of the Salha massacre and its aftermath, interviewing survivors who’d sought refuge in Lebanon, and their descendants. A brief compare-and-contrast between our narrative and Morris’s—representative of the liberal Zionist version of events around the massacre—opens up a wider discussion.

First, the name. “Saliha” is what the Israelis and their British colonial predecessors once called it, imposing a middle vowel. “Salha,” with two consonants in a row, is the closest English rendition of the village name. As for the massacre that took place there, Morris considers the possibility that the impetus behind it—and behind many others—might have been somehow retributive. The implication being that it was, at least to some extent, deserved.

If one relies on the sources Morris considered legitimate, “details about most the atrocities remain sketchy; most of the relevant IDF and Israel Justice Ministry documentation—including the reports of various committees of inquiry—remain classified” by the government. Despite recognizing their limitations, Morris doesn’t really stray from these sources, and the narrative of the “atrocities” he constructs has been endorsed by the state that perpetrated them.

Morris claims, citing IDF archives, that people had been “crowded into…a house, possibly a village mosque” that was then blown up. Survivor testimonies instead corroborate that individuals were lined up single file, after handing over their guns, and shot one by one. After the massacre, villagers took the bodies into the mosque. Morris first placed the death count between 60-70 persons, then in later work between 60 and 94—quite the range. According to the families of the martyrs, 105 people were killed.

That the title of Morris’s book, which documents enormous harm, starts with the word “birth” reveals his politics: he insists that the Nakba was necessary for the creation of the Zionist state. Elsewhere in his characterization of the massacre, he quotes the diary of Yossef Nahmani, the director of the Jewish National Fund in the Galilee,

In Saliha, [where a white flag had been raised] … they had killed about sixty-seventy men and women. Where did they come by such a measure of cruelty, like Nazis? … Is there no more humane way of expelling the inhabitants than such methods?

The second ellipsis hides an admission. In the original entry (translated by a different source), Nahmani answers his own question: “Where did they find such a degree of cruelty like that of the Nazis? They learned from them. An officer told me that the best of the [soldiers] were concentration camp survivors.”

Morris’s project can be understood as establishing a narrative that gets ahead of the victims’ accusations. He uses selective evidence to establish credibility, and he deploys this credibility to circumscribe the conversation. Israeli historiography has always been an arm of Zionist state-building, and every archival document approved for release by the Israeli military functions as controlled dissent to cultivate the belief that the Zionist project, however flawed, is ultimately redeemable.

That I opened in two places with the Zionist perspective, even if to say it’s inaccurate and insufficient, reveals a discursive trap: I find myself undermining their language, falsifying their claims and the narratives these produce, before I —and as reason to—pursue our own. Some of this has to do with perceived legitimacy: working within the “official” historical tradition, digging through state archives at university libraries, carries more cachet than interviewing elderly survivors in their homes; passports and pictures stuffed away in tin boxes are somehow less real than those alphabetized and carefully preserved in laminated binders.

Nahmani, however important his role might have been, writes into a diary, and Morris cites it as part of the “official” record. How are his journal entries materially different from those of someone like my grandfather? Do bigger words and better prose expand credibility? What makes Nahmani, a person committed to ethnic cleansing, more trustworthy than anyone else, least of all his victims? Behind every confession he makes are many he doesn’t, and why should we hold our breath if we believe ourselves? Instead, we cede the center, then try to shorten the radius.

The scientific process accommodates different geographies: a passport is a passport, a diary entry is a diary entry. We use their facts. We cite their sources. We visit their archives and we read their studies, armed with the understanding that they exist in service of a particular goal. And it is this goal—Zionist state-building—that we reject, and it’s through that ideological lens that we should sift this material. Palestinian writer and revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani wrote of the importance of reading Zionist texts in service of “knowing your enemy.” In our study of the colonial psyche, what they will say silhouettes what they won’t, and it’s the latter to which we should pay particular attention.

We’ve seen over and over how Israeli lies serve as distractions. They say without evidence that Palestinians bombed their own hospitals or killed their own journalists, and we spend time backspacing their claims as Israeli snipers shoot into maternity wards. Always, what’s under discussion in Western media is kept peripheral to the reality of Palestinians, as with the extensive coverage of protest chants and college professors and congressional hearings. Meanwhile, there is an actual genocide ongoing in Gaza, which, despite the recent ICJ decision, still largely isn’t recognized as such in the West.

Edward Said published “Permission to Narrate” in The London Review of Books in February 1984, less than two years after the end of the Israeli siege of Beirut. In the essay he moves through a representative cross-genre sampling of the many books written about the occupation of Lebanon: international investigation, ethnography and testimonial, geopolitical analysis.

As its title suggests, Said is interested in the importance of narrative frames—what they are, what they do, whom they serve. He starts with an international fact-finding mission’s report, writing, “despite the MacBride Commission’s view that ‘the facts speak for themselves’ in the case of Zionism’s war against the Palestinians, the facts have never done so, especially in America, where Israeli propaganda seems to lead a life of its own.” The Commission corroborated, after the fact, what the Palestinians and Lebanese had been saying all along, that this was an attempted ethnocide and genocide. Said wanted something else. “Getting the facts right” is never enough: the MacBride report “had no appreciable effect.”

I’ve been thinking about all the ways Said’s response continues to resonate. Weeks after it might have been useful, after not a single hospital remains operative in northern Gaza, The Washington Post confirmed that the evidence of militant bases under Al-Shifa offered by Israel “falls short.” They take their time to say what we already know, under the guise of “thoroughness” and “independent verification,” because, they say, there are real stakes to getting this right, stakes realer than people. The Washington Post and other state-adjacent media like it, these same sources that don’t hesitate to circulate Israeli propaganda to manufacture consent for our extermination, concern themselves with facts once the facts are no longer of material consequence—a cheap attempt to reestablish their own credibility in advance of the next time they’re called upon to inject doubt into intuitive explanations that follow historical patterns. Often, it works: well-meaning people circulate their Instagram posts as some sort of vindication: they said we were right! Well, angled less generously, the Post said, “the historical record matters after Israel has done what it wants.” Considerations of narrative legitimacy—truth in service of what?—should include temporality. Twenty-thousand people are dead. “A historic human toll,” another Post Instagram post announces.

Said repeats various iterations of this phrase, that “the facts don’t speak for themselves.” Narrative frames serve not just to establish reality, but also to give the facts their political valences. Truth in service of what. While he lauds the ambition driving Noam Chomsky’s The Fateful Triangle—an exploration of “the character and historical development of [the United States’] special relationship” with Israel or, in Said’s words, the “panorama of stupidity, immorality and corruption”—he holds that the book is “not critical and reflective enough about its own premises, and this is partly because [Chomsky] does not, in a narrative way, look back to the beginning of the conflict between Zionism and the Palestinians.” Chomsky relies almost entirely on Zionist sources, and while he spends hundreds of pages systematically refuting these sources, offering readers a “dogged exposé of human corruption, greed and intellectual dishonesty,” he offers us little in their place.

Chomsky’s case, Said argues, pays little attention to Arabs; it “would make more sense if, included in it, there could be some account of political, social and economic trends in the Arab world.” Palestinian scholars have shown us what it can look like to establish our own histories in service of narratives rooted in our own geographies and political trajectories. There exist at this point many several-hundred-page books about the Nakba, drawing on decolonial methodologies to weave oral history with anti-Zionist “official” sources and, with the appropriate considerations, Zionist archives. These share what Western sources often lack—namely, they center Palestinians with specificity, as a people. They’re incredible scholarly feats, sometimes spanning a hundred years or more.

But no project is without its limitations, deliberate or otherwise. A consistent narrative gap I’ve noticed in histories of the Nakba is the marginalization of certain dispossessions: because the Nakba is decidedly Palestinian, non-Palestinians ipso facto fall outside its scope. Take Salha: despite its death toll being among the highest of the Nakba’s massacres, Salha goes almost entirely unmentioned in Palestinian historical accounts. The exception underlines the rule: Walid Khalidi’s All That Remains, a detailed portrayal of the more than 400 villages depopulated—and often destroyed—in 1948, is one of the few accounts of the Nakba to mention Salha. Khalidi’s main source on the massacre is Benny Morris. And in Lebanon, too, Zionist transgressions against southern Lebanon during the Nakba, are not well-known outside of the South.

Salha reveals a constraint on the current narrative frame, one imposed by colonial borders. The village’s inhabitants belonged to Jabal ‘Amil, the Shia-predominant community of southern Lebanon, located on the French side of the border at the start of the Mandate period. In the early 1920s, the French-British colonial maps were edited at the behest of Zionists, who hoped to shift some of Jabal ‘Amil’s exceptionally arable land (due to the Litani River which courses through it) into their future state.

Salha and other villages became Palestinian, and their inhabitants, who crossed the immaterial border sometimes daily for trade or to see family or to escape their colonizers’ jurisdictions, largely went unbothered by what their colonizers called them. Until 1948. After the massacre, survivors fled to Lebanon as Palestinian refugees. To make the case for Lebanese citizenship—in service of self-preservation, as Palestinians constitute an underclass in Lebanon—Salha’s inhabitants, and other Shia Palestinians, argued that because there were no Shia Muslims in Palestine outside of Jabal ‘Amil, the Shia were necessarily Lebanese. The inscription of sectarianism into Lebanon’s political infrastructure—as the French and other (neo)colonial powers have done and continue to do elsewhere—gave force to these arguments on the path to citizenship.

This is how my grandfather was born Palestinian and became Lebanese in the 1980s. En route, The United Nations (the colonial powers stacked up in a trench coat) tried to make the offer of Lebanese citizenship contingent upon survivors’ renunciation of their right to return to their homes. What good is a “right” if you’re asked—by the same institution that mandated said “right,” mind you—to hand it over, all so you might qualify for other rights? One couldn’t be both Lebanese and a 1948 refugee, as this would decouple grievance from national identity, or rather extend it to multiple identities. Which is to say, it would make Israel look worse and the UN’s “Question of Palestine” harder to contain.

Narrating Zionist violence along national identity serves a strategic aim: by keeping the victims artificially apart, attention is taken away from the singularity of the aggressor’s goal. The implication, that these peoples from two different countries have two problems to work through separately, collapses in the case of Salha, as it did in Lebanon throughout the 1970s and 80s.

On the ground, it’s never been true. Lebanese Revolutionary Soha Bechara wrote in her memoir Resistance, about the Lebanese so-called civil war, that “Lebanon has only one occupying power: the state of Israel…. As I saw it, the Israeli authorities had kept up the same strategy for decades, and their decision to occupy the South of Lebanon grew naturally from it. This was to continue expanding Israel’s borders.” Israel called their invasion of Lebanon in 1978, ostensibly to target Palestinian militants, “Operation Litani,” as in, the Litani River responsible for much of southern Lebanon’s arability, as in the same land Zionists had hoped to take for their future state back around the time of the Sykes-Picot agreement, when the French said no and gave them instead, through the British, the land that included Salha.

Operation Litani failed, as did the land-grab operations that followed. The separatist frame’s obvious colonial logic, the same logic which separates the West Bank and Gaza, plays into a sort of defensive divide-and-conquer strategy by minimizing the breadth and consistency of the harm across the Blue Line since the start of the Nakba. And the Nakba continues, as do the acts—narrative and material—that refuse dispossession as the final word.

Our grievances and struggle are about the land. Of course, this isn’t to deny the specificities of our traditions and peoples. Still, for as long as occupation lasts, I’m less interested in the question of whether Salha, the land, is Lebanese or Palestinian.

Centering visibility as a measure of narrative success is often a distraction. As Said noted back in 1984, “paradoxically, never has so much been written and shown of the Palestinians, who were scarcely mentioned fifteen years ago.” We’re almost 40 years on from Said’s essay, and there are more Palestinian op-ed contributors and Palestine correspondents than before. It’s not the Western media coverage, about or by us, that shifts the needle.

“[Palestinians] are there all right, but the narrative of their present actuality – which stems directly from the story of their existence in and displacement from Palestine, later Israel – that narrative is not.” Western media has turned talking about Palestine without talking about Palestine into an art-form. Native informants lend their voices to the cause. Stories about dispossession and dehumanization, versions of atomized life suspended above history and land and most of all future, drive individual careers. “Permission to Narrate,” has come to mean “more Palestinian voices,” although this is fairly removed from what Said was writing about.

Said’s critique was that Palestinians should be framed as agents, guided by collective political will and vision, rooted in historical events. A Palestinian writer begging a Western readership to recognize Palestinian humanity places agency elsewhere, and the end of the story at abstract liberal acceptance. For this reason I’ve always found Said’s use of “permission” in the essay’s title amusing, like a rhetorical “can I say something,” before he, as the kids say, goes off. Or, a light shined on the preexisting infrastructure, what it says about Western narrative frames and what they deny, or whether Palestinians require their permission at all.

For as long as our struggle lasts, narrative frames will illuminate and obscure material possibilities. The Washington Post tells the truth after the hospitals are gone, and this functions to sow hopelessness. There’s nothing we, and by extension, you, can do. Despair is presented as a permanent fixture of Palestinian life. This isn’t true, although one has to know better already to see through it. A narrative horizon that extends before and after occupation is one in service of liberation, and against the interests of empire.

Said writes, in the case of Palestine, “where are facts if not embedded in history, and then reconstituted and recovered by human agents stirred by some perceived or desired or hoped-for historical narrative whose future aim is to restore justice to the dispossessed?” Otherwise it’s just suffering, suffering, suffering, impossible to understand what for, impossible to recognize the narrative differences that get one from suffering to struggle. From Balfour until today, our narrative frame is shaped by the same question: not simply “what did Palestinians say,” but “what does Palestine require?” The former should always, always reach for the latter.

Said’s argument is fundamentally about hope. His final critique of Chomsky is,

“In leaving [the problem of allowable claims] unresolved, Chomsky is led to one of the chief difficulties of his book—namely, his pessimistic view that “it is too late” for any reasonable or acceptable settlement. The facts, of course, are with him: the rate of Jewish colonisation on the West Bank has passed any easily retrievable mark, and as Meron Benvenisti and other anti-Likud Israelis have said, the fight for Palestinian self-determination in the Occupied Territories is now over—good and lost. Pessimism of the intellect, and pessimism of the will… But most Palestinians would say in response: if those are the facts, then so much the worse for the facts.”

“The supervening reality is that the struggle between Zionism, in its present form, and the Palestinians is very far from over; Palestinian nationalism has had, and will continue to have, an integral reality of its own, which, in the view of many Palestinians who actually live the struggle, is not about to go away, or submit to the ravages of Zionism and its backers.”

The picture Chomsky paints, while true, is a shrunken truth, because he does not engage with what Said calls “the point of view of a Palestinian trying, as it were, to give national shape to a life now dissolving into many unrelated particles.” By pessimism of the intellect, we mean all the forces invested in the narrative and material dissolution of our cause. It’s exceedingly difficult to know, whether or not we can see them, that the pieces are there and that they’re part of a whole. Or, it’s not so difficult, if we look to the people of the land, the people who, in Said’s words, “actually live the struggle.” Optimism of the will: these dissolved particles can, under the right pressure, at the right concentration, precipitate. Narrative clarifies, and narrative is clarified through action.

The people of the land, for all these decades, aren’t waiting on the particles to settle for the proper narrative frames to emerge. There are other ways to reach narrative clarity than through testimony. One of the women who survived the Salha massacre opened her story with an aftermath: she had, she said, offered her son as a martyr for the cause. Her sister, she added, had offered her son, too. She had lost so much and sacrificed more, and for her entire life she refused to surrender. Narrative clarity follows the will to manifest it. Resistance is a narrative arc, liberation its conclusion.

I register “Avivim” differently because I know its story, which isn’t all that unique. I know there are tens, maybe hundreds, of thousands of people and their children and their children’s children around the world whose ears perk up like mine do, each of our collectives at a single name. The feeling is hard to describe, like a curiosity for how, in a world sustained by our death, we might together hear something else. This, mixed with a strange hope, that there are millions of us who already register these names with friction, as a violence we refuse to normalize. It feels like knowing it’ll take a different world, and also that there are millions of us committed to its realization, acting so some of us will live to see it.

This spring my grandfather passed away still wishing to visit his father’s grave. My grandfather was buried in a cemetery in southern Lebanon, near his mother. My father and his thirteen siblings visit him alone or together, every Thursday before dusk that they are able. They read a certain chapter of the Quran, and they retain, as I do, the promises we were trusted to keep.

When I do visit Salha, in a land that’s called Lebanon or Palestine, I won’t be able to find my great-grandfather’s grave, because it was demolished to make room for something else, maybe—as the Israelis have done elsewhere—a park. I’ll know thousands of people died for this land, and wonder, as I do now, what we owe them, what we owe each other.

It is 2024, and I watch through a phone screen as Israeli bulldozers unearth bodies in a Gazan cemetery. I read that eighty bodies are returned mangled, with missing organs. My first thought: who does that? And then, how does this serve a military objective? I read a UN report that eleven men were lined up and executed in front of their families, and I think of Salha. I read three, then seven, then countless more eyewitness testimonies corroborating the use of this tactic across age and across gender and across Gaza.

I wonder for a moment: if this keeps happening, why I’m writing at all. Their “whispering operations,” psychological warfare in service of ethnic cleansing, have evolved little in 75 years. They’ll always rely on the same basic approach: brute force. They have nothing else in their arsenal, and brutality is an unreliable antidote against a hope big enough to outlast a life. In 75 years, how have we changed? I wish Edward Said could have witnessed the last twenty years, I wish my grandfather were alive today. We trust in ourselves, we invest in ourselves, divide and conquer is less effective, liberation is closer than it’s ever been.♦