In Partnership with the Institute for Palestine Studies

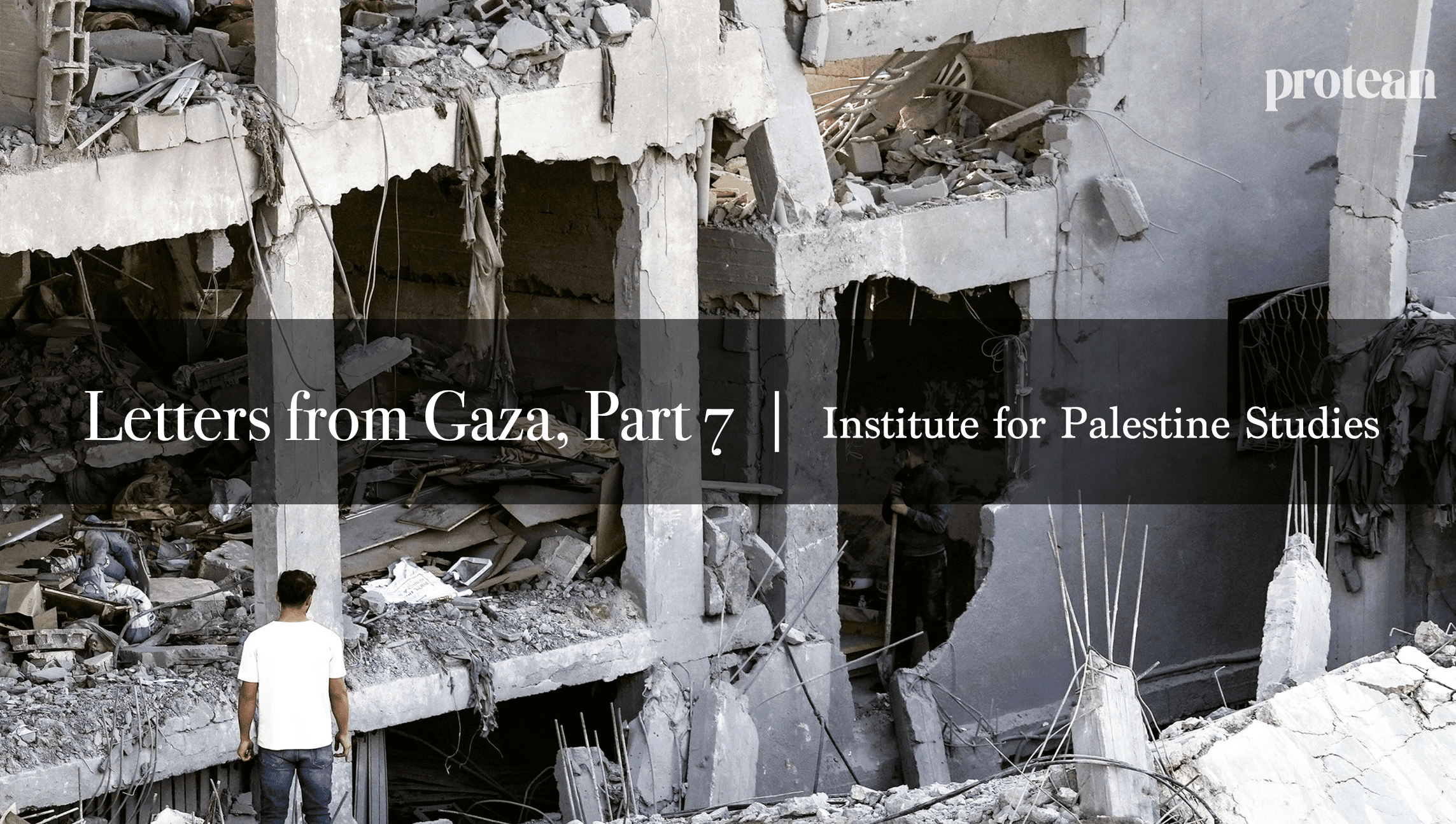

Gaza has gone dark. There are no more working hospitals in northern Gaza. Hunger and thirst are ravaging the population. There is sewage in the streets, and as more and more people are forced into ever smaller enclaves, health officials on the ground are sounding the alarm over the increasingly likely possibility of a cholera outbreak. Mass graves are being dug—and worse, they are being filled. Aid is trickling in, but it is never enough. The “humanitarian pause” is over and Israel has renewed its genocide with even more ferocity, killing over 700 people the same day the pause ended. Journalists on the ground in Gaza continue their heroic efforts to relay the news, but many are beginning to publish their goodbyes as well. Every message that Palestinians manage to transmit may be the last.

The team at The Institute for Palestine Studies has been translating and publishing these messages so that the world can see the humanity buried under the rubble, and the spirit of resistance that has, does, and will continue to animate the Palestinian struggle.

To help maximize their reach, we are republishing these messages here. This is the sixth post of letters—the sixth post in the series can be found here, the fifth can be found here, the fourth can be found here, the third can be found here, the second can be found here, and the first can be found here.

From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.

Ashjan Ajour

November 23rd, 2023

Ashjan Ajour is a Palestinian UK based scholar and the author of Reclaiming Humanity in Palestinian Hunger Strikes: Revolutionary Subjectivity and Decolonizing the Body .

As a Palestinian, I have experienced the impact of colonization on my life and my loved ones, not least now that my close family — including my parents and siblings who survived four previous cruel wars against Gaza — are living under this current intense and murderous bombardment.

Gaza is the world’s largest open-air prison, which is in effect a concentration camp where 2.3 million people have been targeted for ethnic cleansing through massacres and erasures and have now lived in a state of horror, panic, and sumud (steadfastness) for over one month. Palestinians in Gaza, who have been slowly dying from the lengthy brutal Israeli blockade in place since 2007 are now being killed by Israeli missiles and shelling. This genocide is a continuation of the 1948 Nakba that forcibly displaced Palestinians and ethnically cleansed the land of the Indigenous Palestinian people to sustain the Zionist settler project. This settler-colonial machine uses the most destructive weapons supplied by its Western allies to wage war on homes, hospitals, churches, universities, and UN schools where people have been sheltering.

As the world watches the horrific genocide unfolding on TV screens, my family members, like everyone else in Gaza, await their turn to be massacred. The Israeli bombs fell on people in their houses and on their shelters without warning. Entire residential neighborhoods were destroyed and turned into rubble. Palestinians have been portrayed as animals to justify this collective punishment. The Israeli Minister of Defense said they were dealing with ‘human animals’ and cut off access to electricity, food, and water in Gaza. Israel ordered one million Palestinians to evacuate from the north of Gaza within twenty-four hours, an order considered impossible by the UN. This mass displacement is a continuation of the 1948 Nakba with Palestinians repetitively forced to leave their homes. The south is supposedly safe, but it continues to be targeted. There is no safe place in Gaza.

My family left their home to stay in my sister’s house in the south in Khan Yunis. My mother, who had already lost members of her extended family in this war, wept over the phone, grieving the destruction of our home in the Tal al-Hawa neighborhood, which was turned to rubble. Even though I was trying to soothe and calm my mother by saying, “Our home will be rebuilt again,” deep inside I felt that the destruction of our home as the obliteration of our intimate family memory and history. My parents are old and sick and cannot find their medicine amid this horror since hospitals are out of service due to Israel’s targeted bombardment, electricity and communication shutoffs, and a total siege that has prevented vital medicines and supplies from entering Gaza. My sister’s children are traumatized and wake up from their sleep screaming. We find solace in that my nieces have not yet resorted to writing the names of their children on their hands to be identified in case they are killed.

My grandmother’s house was damaged by the bombing. My uncle Mahmoud lives in this house and has a lung condition, he not only lives in dangerous conditions but no longer has enough oxygen tubes to survive. Israel targeted (and continues to target) hospitals and can barely treat the wounded, therefore there is no space for patients with chronic diseases or women that are giving birth, and there is a shortage of life-saving medications. Two of my uncles, Sami and Jihad, decided not to leave their houses in the northern part of Gaza not only because there is no place for them to go in the south but because they would rather remain steadfast; they are willing to die in their own homes because they are scared to be bombed on their way south. According to the Gaza media office, forty-six percent of the overall death toll occurred in the southern area, which Israeli forces claimed was safe. After my cousin’s husband’s house was destroyed, her husband’s parents escaped to the south where they were killed by Israeli airstrikes. She said that her house was destroyed by ships bombarding them from the sea. Other cousins’ homes were also destroyed.

Israel is using internationally banned phosphorous bombs in Gaza. My aunt Safa wondered what sort of bombs were being dropped on them because they could not breathe due to the smoke and had sore throats from inhaling chemical substances. My cousin Samer wrote, “with the sound of every Israeli bombing, we feel that these are the last moments of our lives, and minutes later we discover that they were the last moments of dear relatives, friends, and neighbors. Your mercy, Lord.” He posted on social media: “Dear World! Tell Biden that his green light for Israel was for killing children and women while sleeping! I’m sorry, my daughters, Rita and Karma, but there is no way to protect you and remove fear from your hearts.” His latest post was, “In the 2023 Fall of Gaza, humanity fell before the leaves.” He means that the world cannot stop this criminal madness.

The impact on my family has been transnational. My other cousin Mohamad, who studies and lives in Paris was very anxious about his family in Gaza. He took sick leave from university and came for a visit to be around us here in the UK. He posted, “I shit on humanity if it is not for all humans.” He also posted his conversation with his mom on Oct. 30:

‘Mom, every night passes and I think it’s the worst of my life, then the next night comes and it’s even worse.’

Happy Halloween people, enjoy watching the blood.

A week later he posted again:

He had dreams.

My cousin is crying for her 14-year-old son Bashar who was killed while he was bringing some water for his family who were sheltering in the UN school after the destruction of their home. Rest in peace.

I am here in the UK with my small family. We are subjected to another level of trauma and panic as we find it difficult to cope or process this horror. I ask myself what is happening, is it a nightmare or reality? I find it difficult to respond to my friends when they ask are you okay? Is your family okay? I am not okay. Neither are my family or my children. This ongoing genocidal war in Gaza and what my family is going through is impossible and has made me sick both mentally and physically. I have been consumed by this hellscape that is as bad as it can possibly get for me in every single way. To witness my loved ones and my people living this horror is beyond my capacity to handle. I suffer from sleep deprivation and when managing to get some sleep I wake up running to my phone to make sure that my family is still alive. I then find a message from my mother praying for us and saying goodbye. The hardest days of my suffering were when I was no longer able to reach my family due to electricity cuts. This was devastating. I lost contact with my family and lost my mind as well. One of the worst moments was when we read in the news about a house being bombed in the middle of KhanYunis where my family now resides. I screamed and was about to faint thinking that my family had died. But then we found out that it was the house next to them. My sister messaged saying that she had been out to get some food when the bomb fell on her neighbor’s home.

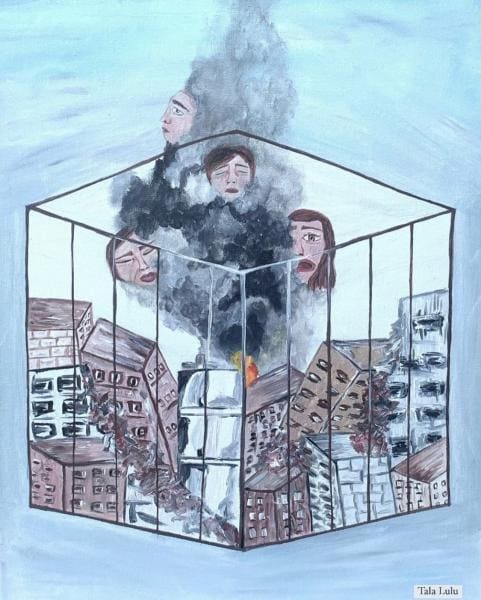

I gathered my strength to write this piece and to take care of my family here in the UK and support my children who have been anxiously watching the TV and are on social media all the time. My daughter Tala could not continue with her internship in London and my son could not attend his college because of their extreme anxiety about what is happening to our people in Palestine. Instead, Kareem chose to volunteer for a restaurant that organized a charity day for Gaza (100 percent of profits were donated to help Palestinians in Gaza) and my daughter participated in several protests in London and produced some paintings on Gaza. Both donated to the victims of the war who are suffering Israeli bombardment without food, water, and electricity.

Painting by Ashjan’s daughter, Tala.

Bushra Khalidi

November 29th, 2023

Bushra Khalidi is a policy lead at Oxfam based in Palestine.

[The following is a transcribed testimony collected via Whatsapp messages from the author’s relatives.]

Conversation with the author’s brother-in-law on Nov. 3, 2020 — Remal, Gaza City (on WhatsApp):

We feel like rats trapped in a cage. Gaza City is completely sealed off, with no one allowed to leave, and it seems like they’re planning to bomb it heavily. Al-Shifa [hospital] is in a terrible state — a literal mess. The sewage is overflowing, and the flies are enormous, like “bodybuilders;” they’re everywhere. When you try to swat them, they hardly budge because they’re so big and numerous. The constant sound of the drone, the zanana, is loud and ever-present in the sky. Our meals are simple: cheese, bread, cucumber, zaatar, and on a good day, we might have tea or Nescafé. That’s all we get. We’re starting to learn the sounds of new bombs, ones we weren’t familiar with before. Even as we hear the loud bombing in the background, we talk about our last good memories. The other day, before all this, while having crab, fresh shrimp, and squid, we were saying how Gaza is the best place, jokingly adding, “Except during war.” It feels like we’re just waiting for our turn now.

Conversation with brother-in-law via WhatsApp on Nov. 4, 2023 — Remal, Gaza City

Indeed, the al-Shifa [hospital]/Remal area is being bombarded relentlessly, and with white phosphorus — it’s a nightmare. But what’s even more shocking is what’s happening among families there. They’re fighting over water. This is serious because, in Palestinian communities, people are known for their generosity and close ties. To see them now fighting over something as basic as water shows just how extremely difficult the situation has become. Water has become a luxury, and its lack-there-of is ripping apart the fabric of our lives. It’s a grim new chapter in this war, hitting people where it hurts the most.

Evacuating south

A conversation with the author, her brother-in-law, and her husband via WhatsApp on Nov. 9, 2023, after the family arrived in Deir el Balah from Remal.

I couldn’t sleep the night before making the journey from Gaza City to the south. Throughout the night, there was fighting at our front door. Nightmares of the soldiers at our doorstep haunted me. I wasn’t sure if I was dreaming. I was exhausted and had only had intermittent slumber, jolted awake by gunshots, grenades, and explosives.

The following afternoon, we managed to leave the house after securing a car. It took us as far south of Gaza city as possible, and then we started our long journey on foot.

Later, we found a donkey with a cart, which we rode for about 30 minutes. Then we resumed walking without an end in sight.

At some point, we reached a junction with thousands of Palestinians, arms raised in a show of surrender, holding our IDs in one hand. Despite the strain on our arms, we continued to do this for around 30 minutes because everyone else did so.

Then we were stopped. In the distance, an Israeli tank loudly addressed us through a microphone.

The first group was allowed through a makeshift checkpoint marked by a massive tank. More tanks were visible further away. The second group, which we were part of, was halted. I was terrified, having never witnessed anything like this. To our right, we could hear the sounds of distant fighting.

The Israelis were making room for a convoy of 12 tanks. We were stunned by the sight, having never seen anything like it. Soldiers were inside the tanks, not on the ground. A Merkava tank and Israeli flags adorned the war vehicles on a distant hill.

A woman in front of me was praying, visibly terrified and shaking. I reassured her, saying they were more frightened than us.

Then, a soldier’s voice rose from the tank: “Anyone with information about the hostages, come forward.” The woman started crying, insisting she knew nothing. I tried to soothe her, telling her not to worry as nobody had accused her.

The scene around us was horrific: disintegrated bodies, body parts, an overwhelming smell. We saw children’s clothing among the dismembered remains. The stench from the wadi (valley) was suffocating, and we endured it for two hours of walking.

Eventually, we took a break on a donkey cart, smoked a cigarette, and your mother rested. We then met journalist friends who drove us the final 10 minutes to al-Bureij.

The situation reminded me of a Mahmoud Darwish book, where he discusses his displacement in 1948 by Israel from his northern village on trucks. Here I am in 2023, displaced by the same army, but on a donkey. What kind of world is this?

Your father and mother were incredibly resilient. But your mother finally broke down, feeling safe enough to do so. It’s astounding how the fear for your life propels you to keep going for hours with backpacks and luggage, especially considering your elderly parents. This is terror. Why this slow death? Why like this?

Reema Saleh: To Escape from Death and Face Death Again, Conversations with My Family

November 21st, 2023

Reema Saleh is an intern at the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut.

I am overwhelmed with embarrassment when I share the struggles of my family in Gaza, especially when others, also in Gaza, are suffering the worst conditions of death, torture, and genocide. But from what my mother tells me, I’ve come to understand that surviving airstrikes doesn’t necessarily mean escaping death. The threats of hunger, thirst, inconsolable grief, and disease are ever-present. These conditions, which include starvation and deprivation, are forms of and can be seen as acts of genocide, just as horrific as missile attacks and the use of internationally prohibited weapons.

My sister, Nour, shares stories of disease spreading due to accumulating waste, fly infestations, and fluctuating weather conditions— scorching during the day and freezing at night. Many displaced individuals lack adequate blankets and winter clothing. The public toilets, currently being used by thousands, pose a significant risk for infections, fever, diarrhea, influenza, and other contagious diseases. On the rare occasions when the internet connection is stable enough for a video call, I glimpse the harsh reality my family is living in — mounds of garbage and swarms of flies that churn my stomach. I constantly find myself questioning whether will they succumb to the lack of basic necessities or the absence of medication, especially for those battling chronic diseases.

My cousin, Lama, is battling kidney failure and requires daily kidney dialysis. However, as of today, November 15, she has only been able to receive treatment using makeshift, unsterilized equipment within an exposed and ill-equipped tent. Her mother bitterly awaits her daughter’s inevitable fate, perhaps finding some comfort in the thought that her daughter might finally find peace.

During our last conversation, Lama’s once vibrant features were barely recognizable due to fluid and toxin retention in her frail body. She told me: “I want Israelis to stop bombing hospitals. Why would they bomb Al-Rantisi Hospital?! And I want them to open Erez crossing so I can get my medication. I don’t want to die.” This heroic girl, who was never afraid of death, is now clinging to life, refusing to surrender to the brutality of an enemy that seems only to understand the language of blood.

What troubles me most is the situation of my five-year-old niece, Joury, who suffers from epilepsy and has run out of medication. Without her twice-daily doses, she experiences severe seizures that could potentially lead to paralysis — God forbid. It breaks my heart that her medical condition hasn’t been accurately diagnosed due to the Israeli blockade preventing Joury and her parents from traveling outside Gaza to seek specialized diagnosis and treatment. Most neurologists in Gaza believe her illness is a result of her mother inhaling the smoke of internationally banned white phosphorus bombs used in previous wars. Each day, I ask my sister Nour if they’ve found Joury’s medicine, but the answer is always “no.” She tells me that her husband, Ahmad, spends hours every day searching for an alternative for their daughter’s medication but always comes back empty-handed.

Despite not being able to communicate with my family for five days, I continued to send messages, hoping for a reply. I find myself asking, “Did you find food to eat? Did you find drinkable water? Were you able to get clothes, blankets, or anything to help fortify your tent against the upcoming winter rains?” Now, they can’t even decide if rain is a blessing, providing them with much-needed water or a curse, as they face the elements without proper shelter — only a flimsy tent stitched together from fabric scraps that constantly fall on their heads.

My father shared with me that a week ago, they had to resort to eating expired biscuits for breakfast. They’ve only been able to secure bottled drinking water twice in the past month since being displaced to the south. Even if they’re fortunate enough to secure more than one meal a day, my brother Mahmoud tells me he limits himself to one meal daily to avoid the long lines at the public toilets. As a result, the gaunt faces of my family members, who have lost significant weight due to the starvation tactics employed by Israel against all Palestinians in Gaza, are no longer surprising. The enormity of the situation is beyond what TV cameras and social media posts can capture.

In another tragedy, my friend Jullnar, with whom I’ve only managed to speak three times since the aggression began, shared her experience of being displaced twice. Their home in the Al-Nasr neighborhood was bombed without warning, as was her husband’s family home, which was hit by Israeli tank shells, leading to the martyrdom of her uncle. She and her husband fled to the center of Gaza City, uncertain of the fate of the rest of her family. Jullnar, who has had three miscarriages in the past and went to great lengths to carry her baby to term, lost contact with her private doctor and couldn’t get the daily injections she needed to maintain her pregnancy. She shared with me through WhatsApp messages her experiences of bleeding and pain over the past few days, unable to reach a doctor or a hospital. She can’t even get the results of bloodwork tests she had before October 7, as she had hoped to communicate with a doctor outside Gaza to answer some of her questions, determine the dosage she should take or the date of her delivery, and whether the birth would be natural or a cesarean section.

And then there’s Fatima, my cousin, the only member of my family I managed to talk to in the last five days, who told me she’s embarrassed to even talk about the quality of the water they drink and the food they eat. She explains how it is hard to explain to her six-year-old sister, Joud, who has diabetes, that she can’t receive her injections even if they are available because there are no open pharmacies. Even if they find one, there are no refrigerators to store her injections! She pleads with me to stop my questions as the answers leave her wounded and choked up. And this is how any conversation I have with my family in the southern part of the Gaza Strip ends — in a cloud of bitterness and helplessness.♦

[Translated by Aya Jayyousi.]